Cara Ellison on: The Poetics of Space

"Well, maybe you need to learn..."

Each Saturday, one of our four regular columnists will be taking turns to fill the weekend opinion slot here on Eurogamer. Today it's Cara Ellison. You can find out more about the columnists in this editor's blog.

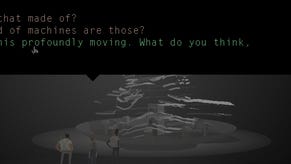

There is an important part in Kentucky Route Zero Act II when Shannon says, "Are we inside or outside?"

You can choose between three answers: "Inside." "Outside." Or "Both."

My first game, Acheton, a fantasy adventure text game on the BBC Micro, was unforgiving but it gave death quietly, brutally. The scratching noise of the disk drive is drawn into my mind as if by seismograph. Screens and screens of that white angular font on black were the reason I learned to read so voraciously. Those early days of text games had such an incredible mysterious quality, like throwing a stone into the dark and having a glittering gift thrown back. I remember Nolan Bushnell telling Simon Parkin:

"When [my son] was about three he said: 'Dad, I could do a lot better on this game if I knew how to read'. I said: 'Well, maybe you need to learn'."

How many children learned to read by typing into a text adventure on an early computer? And not to 'win', just to explore and to read a response? To stretch into the abyss, alone, and throw a stone in? To look? To peer? Were we gamers then, when text adventures were new? Or just flirting in the dark?

Are you inside or outside? You are in the hallway of a disused farmhouse.

One Christmas I took my laptop home and asked my mother if she would like to play Proteus, a first person game where there is nothing to do but wander around a sun-saturated, colourful island populated with frogs, squirrels, crabs on a mosaic beach. Each object on the island makes music that contributes to an atmospheric symphony; there are no objectives but to wander. My mother delighted in it; it made her slightly motion sick, but she liked it. Afterwards she said so, and then she added, 'but it's not a game'.

I can't begin to tell you how disappointed I was. I tried to interrogate her about why she thought this. The term 'game' was only to be applied to the sorts of games that she didn't like. Proteus was different to her. It meant something else other than game to her. She loved it so it was not a game.

Are you inside or outside? You are on an island, by the singing flowers.

In Kentucky Route Zero Act II Shannon asks Conway, "Are we inside or outside?"

Shannon's line is a reference to Gaston Bachelard's "The Poetics of Space" written in 1958. Earlier in the game the character Lula Chamberlain opens a rejection letter from the "Gaston Trust for Imaginary Architecture" which is a direct reference to the French philosopher's work. Bachelard's "Poetics of Space" is probably the most important book that most game designers have never read; it explicitly connects architecture to how people will experience it, rather than the trend in 1958, which was to treat architecture like spectacle. Bluntly speaking, Bachelard said back in 1958 that games are not just graphics. They are architecture that create an experience. He would have made an excellent level designer.

In the chapter "The dialectics of inside and outside", Bachelard writes, "Outside and inside form a dialectic of division, the obvious geometry of which blinds us as soon as we bring it into metaphorical domains. It has the sharpness of the dialectics yes and no, which decides everything. Unless one is careful, it is made into a basis of images that govern all positive and negative."

Bachelard goes on to argue that we should abandon the idea of the diametrically opposed 'inside and outside', that we should continually think instead of how they both serve the poet, the human experience, and are unified in this way.

He seems to have predicted the video game tendency to focus on the binary, to say that there must be a decision between one thing or another, there are only two ways it can go, and those two ways are either positive or negative. Games have always been in this eternal fight, a struggle to say whether they are art or science, when both concepts are artificially constructed and maintained, and artificially juxtaposed. Bachelard thinks that this can hobble human experience and imagination. In video games it could contribute to dividing the actual and virtual experience even further than we want.

Recently, games have attempted, at least in narrative, to break down the binary. The Walking Dead notably provided a player with decisions that almost always had a number of set outcomes all with difficult consequences for many different characters, folding out both quickly and slowly over a number of episodes. This created a feeling of uncertainty as you come to realise that there is no 'yes/no' narrative, there is only what happens, which cannot truly be predicted and once chosen cannot be reverted. There is less control, but the emotions evoked are a slow build, with an equally good pay off.

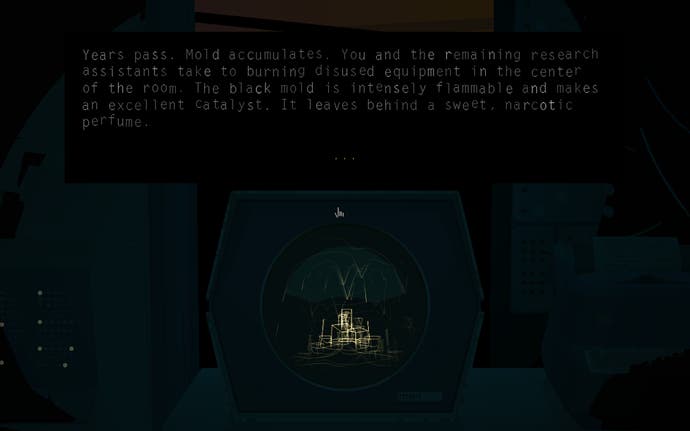

Kentucky Route Zero concertedly removes the player of the binary. The focus is on how the structure of the narrative, and the composition of the art on screen, evokes a feeling of being both inside and outside at the same time. At one point in Act III you are invited to play Xanadu, a text adventure that is a metanarrative of Kentucky Route Zero. There's a crude television screen showing lines and shapes, and a printer next to it prints out the text line by line. You become confused about being inside or outside the narrative. Will choices in this metagame affect the game's storyline? Are the character's choices outside of the metagame working in the same way as the textual choices in the metagame?

It rewrites history for me: it makes Acheton not about death, but about memory, about myself. The text options I choose in Kentucky Route Zero are a reflection of my own interpretation of language. In Act III, you are asked to participate in choosing the lyrics of a song being played out before you. You choose from "When you left me... / I never should have met you.../I wish we'd met before..." Each time I choose, it is reflective of the tone I want that day. It expresses something about how I feel. It tells me more about the kind of player I am than any game I have ever played.

"Are we inside or outside?" When I choose the reply "Both", I know who I am.

Kentucky Route Zero is episodic and isn't finished yet, but it doesn't really matter. I will leave you with this quotation from Bachelard about architecture, which may as well be about games:

"Maybe it is a good thing for us to keep a few dreams of a house that we shall live in later, always later, so much later, in fact, that we shall not have time to achieve it. For a house that was final, one that stood in symmetrical relation to the house we were born in, would lead to thoughts-serious, sad thoughts-and not to dreams. It is better to live in a state of impermanence than in one of finality."

Many thanks to Dennis Kogel, Magnus Hildebrandt and Benjamin Filitz for this article excavating the influences of Kentucky Route Zero, and to Ansh Patel for this glorious piece on the musical centrepiece of Act III, which inspired this article.