An afternoon with Torment: Tides of Numenera's DM

Dice another day.

Colin McComb has a soft-edged voice, which offers a nice contrast to the intense stare his face can't help but settle into. Bald and gaunt and wiry in that peculiarly American way, he is what my grandfather would have called a railway man. But McComb is not a railway man. On the day I meet him at Rezzed, he is a dungeon master: the same preoccupation with nuts and bolts as a guy who rides the rails, perhaps, but these nuts and bolts hold together story and far more exotic materials - and McComb's rails can take you anywhere.

Most of the time, McComb's job offers a strange contemporary twist on the DM role: he is the creative lead on the video game Torment: Tides of Numenera. This is the long-awaited spiritual successor to the beloved Infinity Engine game Planescape Torment - sufficiently long-awaited and beloved that its Kickstarter in 2013 broke records, eventually netting the developer inXile just over four million dollars. It is also more than that, though, and this brings us back to McComb's one-off DM gig at Rezzed. The new game is based on a pen and paper RPG called Numenera, itself a recent Kickstarter success. McComb is going to allow Eurogamer's Bertie Purchese and I to play Numenera with him. Not the video game, which is still in development, but the pen and paper one. We are going to attack things and grab loot. McComb is going to DM.

He is a perfect DM, and not just because he looks like Michael Keaton cast in the role of Professor Hugo Strange. McComb clearly loves Numenera and knows it inside out, but what really elevates him is his ability to describe and shape a story as if he, too, is witnessing it unfold for the first time. To a certain extent he is, of course: before we meet, he delivers a speaker session at Rezzed in which he says that Numenera is providing the basis for a video game that is as reactive to player choices as it is deep and filled with glorious incident. Beyond that, though, he simply has that rare ability to sweep people up in a narrative - and to appear swept up along with them.

Numenera offers him a lot to work with, and if you're after an insight into the forthcoming video game, here's the stuff you'll want to know. The world of Numenera is Earth, but Earth a billion years in the future. Many civilisations have risen from the soil to rule the planet since the present day, and a lot of these civilisations were not human. Some of them have reached the stars. Some of them have reached beyond, gaining the power to manipulate entire solar systems and build huge chunks of architecture out there in the galaxy. Some of them have reached beyond that even, twisting time and exploring different dimensions, creating empires that span the universe.

You will not play any of these illustrious heroes. What would be the fun of that? Instead, you'll be a lowly old human idiot, recently re-emerging on the scene and landed in a world that now exists at a medieval level of sophistication. This world is still riddled with the relics of the last billion years, technological trinkets that, to lean on Clarke's third law, the surviving humans will struggle to distinguish from magic. These trinkets are the Numenera: ancient, horribly advanced gadgets that could be just about anything. Weapons, vehicle components, obscure torture devices. They're loot, the acquisition of each one offering both a new way of playing, and a reason to play in the first place.

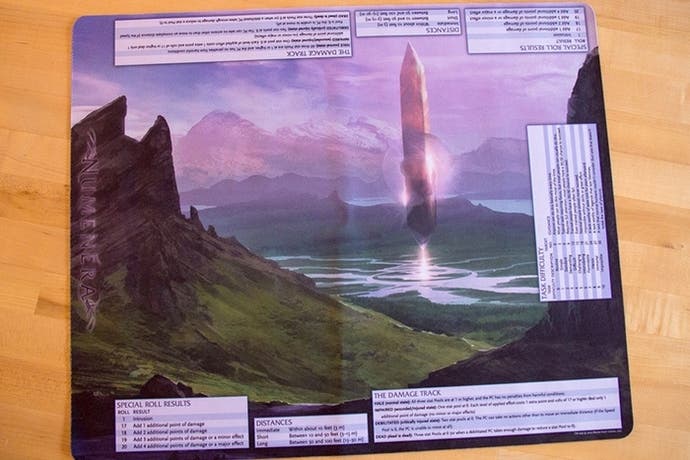

McComb starts Bertie and I off in a valley: two wooded banks with a silvery stream running between them. Alongside the two of us, we are joined by a European journalist who brings Peanut M&Ms for everybody, which is always money in the bank, and Thomas Beekers, an associate producer on the Numenera video game. Classes here initially seem esoteric and hard to draw a bead on, or maybe they're entirely straightforward and I've just had too many M&Ms. What's more important for a short game like this are basic stats, covering staples like Might, Speed and Intellect, and the gadgets we have with us: one-shot pieces of tech that will hopefully be useful when we get in a fight. I am carrying something called a Sonic Hole, apparently: a name so weird I can't bring myself to ask what it is. After a few minutes of play, I also discover a strange tube that allows me to learn the exact weight of anything I point it at. This is going to be super useful for protection when exploring a dangerous medieval world filled with tooled-up lunatics. Bertie, meanwhile, has a device called a Shocker. It shocks people. In a moment of ennui, I find out how much it weighs. Not much.

There aren't too many moments of ennui, inevitably. McComb kicks things off in fine mysterious style: as we enter the valley, a huge sphere has landed in the stream. It is made of some strange, alien material: silvery, with no visible seams or joins. Worryingly, it's surrounded by dead fish, sloshing about in the water.

Dead fish? One of the classic calls to adventure. Clearly we're all ichth-ing to investigate, but we have to wait a few minutes. On the other side of the valley, we hear the sounds of an approaching party. A group of cultists, with a child they appear to have kidnapped. We opt not to fight them - this is more the indecision of a new group of role-players rather than much in the way of strategy - and before long, they've muttered incantations, as cultists are wont to do, and have disappeared inside the sphere.

We rush over to inspect the huge object. After all, I can't wait to find out how much it weighs! It's off the scale, sadly, and that's my one contribution to the party completely blown. Sadder still, as we stand around arguing about how we might get in, it starts to hum and then vanish. Within seconds it's gone.

The cultists have left a bag behind, though. They are also wont to do this sort of thing, and with the stuff it contains we're soon hot on their trail again. The trail leads through a village, where we stop to have a rest and pick up quests. As luck would have it, all the local children have gone missing, and there's a monster that's been sighted in the nearby lake. Coincidence? Nothing is a coincidence in a game that has to wrap up in an hour - particularly when we have yet to fight anything.

The fight that ensues is amazing, as pen and paper RPG fights often are. It's also a reminder, though, that you can't really gain too much of an insight into a video game by playing with the entirely social, consensual storytelling ruleset it's based on. In the lake, we find a single enemy: a crab sort of thing with tendrils that have childrens' heads attached. That sure wraps up the mystery of the missing kids! Sadly, beneath the tendrils is an armoured carapace and a bunch of pincers.

It is a monster to take down, particularly since we barely have any health and weapons to share between us. One wrong move and it grabs you and shakes you around and drops you. Most of the gear we have just bounces off it. Eventually, though, its carapace starts to shatter, and Bertie, who is astonishingly unlucky with the dice today, gets to hit it with the shocker. He cooks the thing, but not before it's pretty much ripped our party to pieces. The townsfolk appear, sobbing, and I limp off to the tube station.

In a video game, something like that will be a boss fight. I can almost picture it: ducking between the swipes, the panic when you've been grabbed and have to endure ten seconds of unblockable damage. Slowly, the model starts to update as you crack the armour. You root through your inventory for something handy to equip. You can't believe how many misses you're getting on standard attacks.

Played around a table, though, it dodges the easy classification of a boss fight - a term that brings so many standardised expectations with it. Battling the crab becomes something horrible that is happening to you right now, and that you need to get past no matter how you do it. The dice rolls - Bertie's persistent failure to get anything above a 6 - were met with groans, protracted theatrical groans from a group of men, some of whom had only really just met each other. Missing was thrilling, as was seeing your health reduced to the point where you were bleeding out on the grass, as was the prospect of wiping entirely and seeing the monster slink back into the sea undefeated.

A video game can't do that. It can't use the people around you to make an old idea fresh. What does make me very excited about the new Torment, though, is not so much that it's based on the clever, engaging, melancholic world of Numenera, but that our guide through the pen and paper game will also be our guide through the video game. It will be fascinating to see how much of McComb's sense of easy wonder survives, how much of his reactive elegance he can get into the code. When that crab beast died, he mimed the tendrils going limp with his fingers, each one shuddering and then falling away from his palm: it was comic, but also wonderfully evocative of a beast coughing its last.

If we get some of that in the final game - not the fingers, but the understanding of how to create the right effect - we're in for a good time. A bad time, obviously, because it's a Torment game, but a good bad time if you get my meaning.