Rich Stanton on: The Koj delusion

Is Metal Gear Solid provocative or just perverse?

Editor's note: this article contains strong references to child abuse which some readers may find distressing.

Oh Koj, what have you done now. For my fellow Metal Gear fans, this week's Quiet doll, featuring squeezable breasts, may have felt a little like déja vu. It's entirely possible to love Hideo Kojima, love the Metal Gear games, and at times be left open-mouthed at how crass and tacky aspects of them can be. When I saw that picture of human fingers squidging together the boobs of a fictional, near-naked woman, my reaction was a big internal cringe.

Metal Gear games are created by an entire production studio and hundreds of people, but more so than any other major series, Metal Gear is also inextricable from writer, director and producer Hideo Kojima. It is his personality that shines through Metal Gear's world: witty, intelligent, perverse, silly, a cinephile and otaku. Though the man himself is almost a cipher, biographically speaking, every fan of these games feels like they know him.

In a sense, we do. video games are a medium, meaning they're a means by which one person or persons can communicate ideas to another. And Kojima is more conscious of that potential than most. This is a guy who made Metal Gear Solid 2, a sequel about how dubious he felt about sequels, and expressed this most trenchantly in making a lead character who would be hated by the players - Raiden, a.k.a. Not Snake - then revealing him as a surly VR-trained Snake-idolising avatar for the players themselves. Few series have survived the generations as Metal Gear has, and even fewer have remained at the pinnacle while doing so - every new entry is an Event, just as this year's The Phantom Pain will be.

One of the subjects Kojima is interested in is sex, and the way it's handled in Metal Gear games runs the gamut. There are fratboy jokes, like making Snake masturbate over a girly locker picture in MGS2, next to moments of sheer perversion like the underwear viewer of Peace Walker. Though Kojima also sexualises men, with butts in particular receiving loving care and the option to go on gay dates offered, overwhelmingly the gaze across the series is on women. And it's not something he's unaware of.

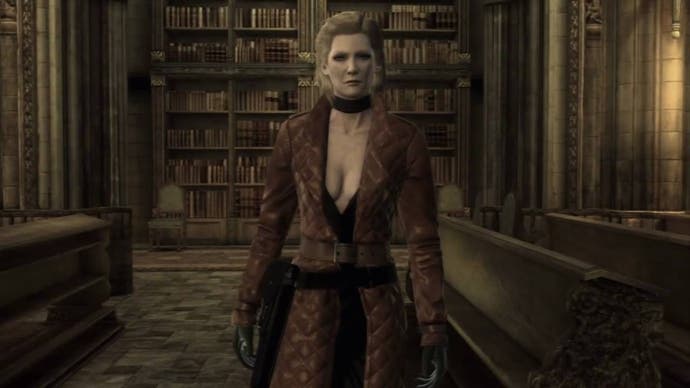

The Beauty and the Beast unit in MGS4 is composed of women traumatised by their experience of war and reshaped by the military to channel this anguish into battle - and in a strange, unsettling coda to each fight, they try to hug Snake when 'defeated' and shorn of their armour. You could argue interpretations of this all day, but then Kojima goes the extra mile and inserts a photo mode. You can, by stretching out the timer in the final encounter, be transported to a mode specialised for taking up-close photographs of these 'beauties' dancing and posing in skintight catsuits.

The juxtaposition is startling. The photo mode seems like simple titillation. In the context of the characters, it's even grimmer. It's hard to see the Beauty and the Beast unit as anything other than victims and, from the man who created them, inserting a pervy viewing mode is surely how this eats its own tail. Exploited by the military-industrial complex, used by powerful men as attack dogs, killed by Snake as mere obstacles, objectified in name and appearance throughout - and then finally, cruelly, needlessly made to cavort in a photo mode for the titillation of young boys. It's hard to shake the sense that this is deliberate.

Something that may not be obvious to a non-fan is the semi-hostile relationship that Kojima and Metal Gear have with the series' most obsessive fans. Kojima returned to direct MGS4 after, so he claims, the team working on it without him received death threats. And so no surprise that MGS4 is, for my money, one of the most vicious and pointed single-finger salutes aimed at a fanbase ever, designed to deliver exactly what they say they want (main character Solid Snake, the convoluted plot with every major character returning, the shattered husk of Shadow Moses) but then casting them as an aged outsider in a world transformed beyond these ideas. Some of Kojima's work is described as fan-service, which is only half-true. The frustrations and petty demands of the 'true fan' drive Kojima crazy and, with a smile, he responds by filleting them for the cameras.

Which leads us onto Quiet, a.k.a. Boobs McGee. Quiet was first revealed over a year ago and provoked a hostile reaction for her combination of a pneumatic figure and a near-complete lack of clothing. My first thought on seeing her was 'Lara Croft pisstake,' and this suspicion of being designed to send up the female action hero archetype only grew stronger when Kojima revealed she was mute.

Now Quiet has returned to the news with the announcement of her action figure, which features squeezy boobs. The doll is a pretty sad sight, and suggests that - whatever the true story of her character - Kojima is not above a gross stunt if it helps with marketing. You could make an argument that ties a squeezy boob doll into the great industry rebuke that Quiet may be, but it still doesn't get over the fact that a video game is producing squeezy boob dolls merchandise.

Following the initial and very mixed reactions, Kojima tweeted this about Quiet: "I know there's people concerning about "Quiet" but don't worry. I created her character as an antithesis to the women characters [that] appeared in the past fighting games who are excessively exposed. "Quiet" who doesn't have a word will be teased in the story as well. But once you recognise the secret reason for her exposure, you will feel ashamed of your words & deeds." He went on to say MGS5's theme was race and the misunderstandings and conflict caused by cultural differences, ending on this note: "The response of 'Quiet' disclosure few days ago incited by the net is exactly what MGSV itself is."

Ambiguity and promises, as is the right of any creator before their work is done. It is worth remembering that, though an international series, both Kojima and MGS are Japanese - a culture where sexism remains more or less the norm. But there's a pointed rebuke at the end too, implying that the reaction Quiet has received was exactly what was intended. Perhaps it's bravado. I can't help feeling that Quiet, and her doll, are intended as Kojima's response to video games becoming more socially aware in recent years, and further to that point the character is aimed at the portion of his audience who think a naked sex kitten is a perfectly fine lead character for a game. That is, the tactic with Quiet is to take what is or has been accepted as the norm in female representation in action games, and then push it to an extreme - both making the audience complicit in her success or otherwise, and showing how ludicrous these principles of character creation are.

I may be being too generous to Kojima here, and falling into the trap of being an unquestioning defender. But what continues to fascinate me about his games is how they upset expectations, and delight in flipping the table on seemingly thoughtless aspects of the design and even the sexual objectification; consider how the player as Naked Snake is encouraged to leer at Eva's breasts in MGS3, then at the end discovers this was a distraction tactic to allow her to steal Snake's prize. Which worked. This is why, even though seeing the Quiet doll makes me cringe to be a Metal Gear fan, there's a little part still saying 'wait and see.'

Kojima thrives on how underestimated Metal Gear is as a narrative vehicle. The scripts range from passable to awful, but the ideas and themes are both original and wide-ranging. Much more importantly, no-one takes them seriously because they're video games. This is why he can make a game like last year's Ground Zeroes, which takes unflinching aim at the modern USA and the War on Terror and condemns the philosophies behind and the realities of its internment camps in such a complete way. You'd be hard-pressed to find a single piece of mainstream entertainment that does this as well as Ground Zeroes.

One example here shows how what may seem to be crass objectification in Kojima's games is rarely so simple. Ground Zeroes received an enormous backlash following release for the presence of an audio tape, late in the game, that revealed Paz had been repeatedly raped while imprisoned. Her comrade and fellow prisoner Chico was forced to first listen to and then observe these ordeals, and eventually was forced to participate on threat of death.

This met with widespread revulsion, and the suggestion Kojima was trivialising rape for the sake of a plot point or, even worse, as a 'reward' for the player. It was further suggested that a game featuring an antagonist called 'Skullface' shouldn't deal with such taboos (which, as an argument, is a non-starter).

Not once was it mentioned that Kojima is explicitly paralleling the rape and torture of Iraqi children by the US military and its allies. There's a harrowing account from an Abu Ghraib detainee of having to listen to an Iraqi boy being raped, a situation paralleled in Ground Zeroes with Chico and Paz. The great investigative journalist Seymour Hersh has spoken of how audio tapes of boys being sodomised in front of their mothers exist "and the worst above all of that is the soundtrack of the boys shrieking that your government has. They are in total terror. It's going to come out."

Hands up if you knew about these abuses perpetrated in the name of freedom and liberty. I didn't either, until Ground Zeroes sent me off looking into the details of US prison camps. Kojima did not put rape into Ground Zeroes for amusement: the game is fictionalising a real-world horror in order to bring attention to it. Don't tell me that armies can rape children, then conspire to hide the evidence, and a creator bringing attention to this in their work is somehow using it as a plot device. Rape may be a taboo but, as any student of history will tell you, it is also a fact of any war. It is fine to have reservations about how Kojima handles the topic, but the attitude he had no right to do so doesn't wash.

The Koj delusion is suffered by both sides. His fans think he can do no wrong, his detractors think he's a wannabe-filmmaker who writes awful dialogue and makes clunky games. I definitely incline towards the former camp, but occasionally - Big Boss's date with Paz in Peace Walker springs to mind - I am disappointed by how childishly perverse Kojima's games can be. In this sense, he's made a rod for his own back: because the Metal Gear games have such a range of tone, moving from the slapstick to the philosophical via the plain crazy, some of the ideas are jarring or unpleasant.

For me, none of this invalidates Kojima's work. No creator is perfect and, if I'm honest, the moments when Metal Gear has stepped over the line seem like a minor part of the overall achievement. That doesn't stop you seeing the Quiet doll and groaning at the sheer crassness of the thing. Kojima clearly has something in mind other than simple objectification, but whether he can manage this from such a starting-point remains to be seen. He may not succeed, but he's one of the few game directors that stands a chance of doing so.

This is the real problem. Our media system of hot takes and instant reactions, circulated through social media, has little room for the multiple layers and nuance of Kojima's themes. Out of context, his designs can be made to look very bad indeed, but the context itself is a barrier - there's just so much of it in any given Metal Gear. Kojima is a game designer who rewards thought, and that's why I'm keeping the faith he'll manage something special. Whatever happens with Quiet, though, will, I guarantee, be more interesting than any hot take can handle.