Sunset review

The revolution will not be televised.

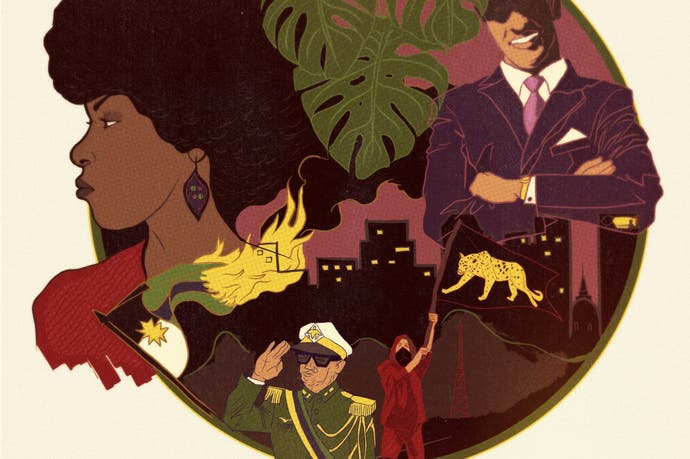

Angela Burnes, a protagonist you only see caught in the reflections of the surfaces that she dutifully polishes, is a kind of inverse Cinderella. Each day, as housekeeper to a wealthy businessman, Gabriel Ortega, she must carry out a number of chores. She hangs his pictures, waters his plants, cleans his ashtrays, polishes his silver and scrubs the floors of his ludicrously sumptuous penthouse apartment, which overlooks the higgledy skyline of the fictional Latin American capital San Bavón, all winking skyscrapers and nodding cranes. The clock is ticking. You have one hour to guide Burnes through her to-do list. At sundown, you are banished from the property, regardless of whether or not the day's work is done.

Many video games replicate the rhythms and routines of human labour. In Sunset there is no metaphor: your time in the game is spent padding around the penthouse (the design of which was directly taken from concept sketches of the ideal bachelor pad in a 1970 issue of Playboy magazine), clicking on points of interaction to perform your duties as a cleaner. You may choose to put a record on the player, or to listen to the radio, or to admire your employer's latest fine art purchase. But Sunset, at its most rudimentary level, is a housework simulator. And even viewed through this most basic lens, it's effective. "There's a kind of peace, wiping away the grime," says Burnes of her work, early in the game. Indeed, the routine grows comforting. Sunset offers you achievable goals and, in a curious way, as you set the date on Ortega's chic calendar for the umpteenth time, you take honest pride in your toil. It becomes soothingly ritualistic.

This is not, however, a pure labour sim. Like Papers, Please, a game in which you play as an immigration inspector for a fictional European country, the work merely provides context and framework for a more ambitious storyline. Outside the apartment the country of Anchuria is troubled. You learn of this via Burne's daily commentary, spoken over the daily chores (and voiced by the actress Tina Marie Murray) and via the sights and sounds of revolution - the screaming jets, the pitter-patter of gunfire, the bulging black smoke of city fires, the raining ash - which can be encountered on the apartment's balcony. Every time you arrive for the next day's work there is change and movement. Some of this change can be seen at a purely domestic level: a new piano here, an Arco lamp there, an occasional re-decoration (the opulence seems to breed at least till, later in the game, it declines), and a window broken by a stray bullet. But change is also communicated by the clues Ortega (with whom you interact only through the occasional flirty note left on a sideboard) leaves around his home. He is, you soon learn, involved.

Burnes is bright and politically engaged. An African American, she left Baltimore to come to South America to study and has wound up as a housekeeper much to her chagrin ("I could have done this in Baltimore," she says). As time passes she becomes emotionally engaged in the country's political situation, and her growing fascination with her employer and his work leads her to become engaged in practical terms too. While Ortega is always absent from the game, a nuanced and complicated relationship between the two develops. Burnes feels admiration for Ortega's expensive tastes, but expresses an equal amount of dismay at the things he buys, which she often considers gauche. Unable to leave the country, she is envious of Ortega's position ("he has options that I am denied and he has the privilege of not choosing to use them") and yet also appreciative of at least some of the ways in which he tries to exert his power for good, in terms of protecting artworks from the regime and, later, seeking to undermine it.

The politics of the broader narrative echo, in this way, the politics inside the apartment. As Burnes, an intelligent, educated yet impoverished woman tries to understand her position with relation to her employer, so, outside the apartment's walls, the people try to negotiate the relationship with their government. At times, the script is preachy. The game does a better job than most at showing its story (through shifting props), rather than merely telling its story through reams of dialogue, but there is a significant amount of the latter too ("You can feel the depression in this place," says Burnes at one point. "How am I supposed to scrub that out?") Despite this, it still leaves some plot points underdeveloped; Burnes sometimes outpaces you in her knowledge and understanding of events, which can be frustrating.

Sunset is unquestionably the most traditional video game yet from Tale of Tales, its Belgian husband and wife development team, whose previous work includes The Endless Forest, an online game commissioned by the Musee d'Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean in Luxembourg, in which you play as a deer who interacts with other players only through sound and movement, and The Graveyard, in which you're cast as an elderly woman who walks between phalanxes of gravestones en route to a bench. As well as the daily rhythm which gives Sunset structure, there is exploration to be done, and rewards for those who are thorough. You have agency here. It's possible to alter the relationship between Ortega and Burnes, or at least choose the pace of its development (a single playthrough can last anywhere between 90 minutes and six hours, the developer claims).

There are moments of humour (you can, if you so choose, arrange Ortega's record collection by genre and title) and in time both you and your character grow attached to this unseen man whom you serve. The game elegantly communicates a very particular kind of relationship in the period world, in all of its power-dynamics and complexity. Some will inevitably find the lack of formal puzzles, collectibles or many of the other attributes of most contemporary video games off-putting. But Sunset, despite its minimalism, is a rare treat. It tells a story about revolution via the reflection of domesticity, an unusual and thrilling use of the video game medium, and one that expands both its scope and its definition.