How the Commodore Amiga changed gaming - and my life

30 years old this week, Dan Whitehead looks back at the computer that landed him his first job as a games reviewer.

I'm here thanks to the Commodore Amiga, that flat beige biscuit of a computer which celebrated its 30th birthday this week, and saw off the 8-bit computers as surely as an asteroid did for the dinosaurs. Admittedly, it was those 8-bit computers - specifically my beloved ZX Spectrum - which got me into gaming in the first place, but it was the Amiga that helped me transition that childhood passion into an adult career.

At a time when the technical advances between hardware generations is harder and harder to perceive, it's easy to forget just how seismic the impact of the Amiga was. Certainly for those of us weaned on the single-digit colour palette and squawking buzzer sounds of the Speccy, the difference between the old and the new was as eye-popping as the transition from black and white to widescreen technicolour in The Wizard of Oz.

Here was a computer that could do sumptuously detailed and colourful graphics. It could produce music that sounded like real instruments. It had games that were in solid polygon 3D and, unlike pioneers such as Driller, these games were smooth and fast. Well, fast for the time, at least.

Of course, I resisted. I loved my Spectrum and, as with any first love, I felt duty bound to stick with it, long past the point where it was clear there was no future. But there was no escape. Magazine ads and even the boxes for games began to favour Amiga screenshots. The big releases began to pass the Speccy by, or appeared late and in shoddy ports. Some things never change.

As the 8-bit market collapsed into a gloopy pile of budget re-releases, desperate compilations and magazine covertapes filled with last year's top games, it was clearly time to move on.

If the Spectrum had been my innocent first love, then the Amiga became my first serious relationship. And, yes, while girlfriend analogies are gross and weird where gaming hardware is concerned, in this case you can blame Commodore for literally naming their computer "girlfriend" in Spanish.

The Amiga occupies a strange place in the natural history of gaming, however. The use of a mouse and a window-based operating system may have been pioneered by Apple in 1983 (in turn inspired by the Xerox Alto from the 1970s), but for most outside the US corporate world - and certainly for teenaged gamers in 1980s Britain - the Commodore Amiga was to be our first encounter with what we now take for granted as the standard way of interacting with a computer: point and click.

For me, it was a revelation - not just because the games I was playing took a sudden upward turn in terms of complexity, but because in doing so I began to see what we'd now call "game design" at work. And that, in turn, transformed the spark that had been set by years of reading Your Sinclair and Crash into a flame.

In my final year at high school, during a meeting with the career's advisor, I told him that I wanted to write about computer games for a living. He looked at me like I'd said I wanted to a job milking ghosts and gently suggested maybe looking for something at a local factory.

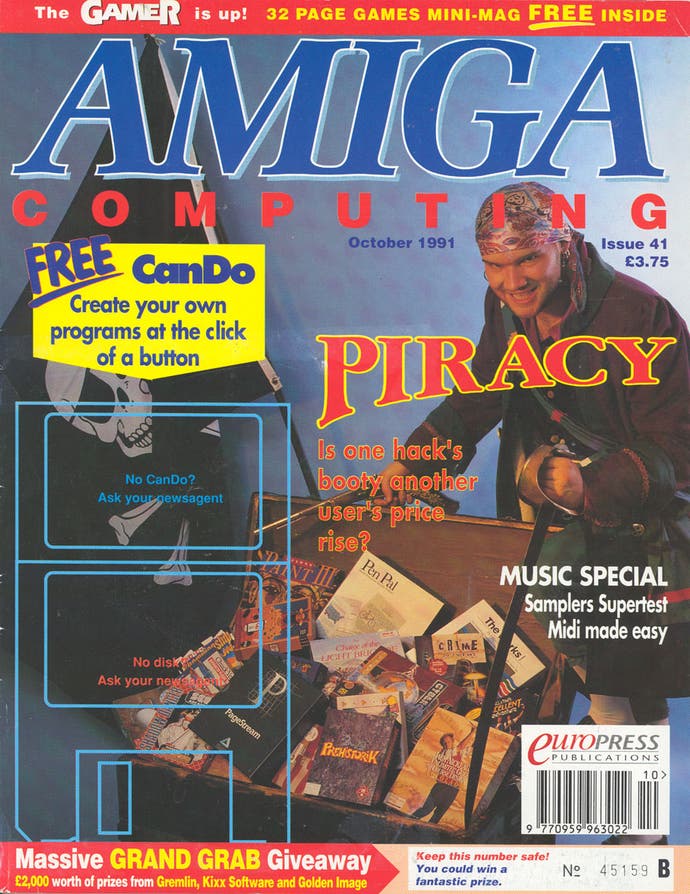

That's where I may have ended up, if it weren't for the fortuitous turn of events that saw a staff writer position for an Amiga magazine from a local publishing company, advertised in the local paper and spotted by my Dad, just as I was finishing my A Levels. I wrote a review of Bullfrog's oft-overlooked strategy classic Powermonger - still one of my Amiga favourites - and got the job. And, more or less, that's what I've done ever since.

My relationship with games changed then. I'd gone from having my parents buy Spectrum games for me at Christmas and birthdays, to buying my own Amiga games - and saving up for the must-have half-meg upgrade - by working at Sunlight Laundry, lugging filthy hospital sheets in and out of enormous industrial washing machines. I paid my dues, man. Now, I was getting every game for free, and got to wax lyrical about them in print to boot. If by "wax lyrical" you mean "rip off Your Sinclair's irreverent style very badly", of course.

My relationship with the Amiga was never as heartfelt as the one I had with the Speccy. I never wore my ownership like a badge of honour. The Amiga's main rival was the drab Atari ST, superior only in its MIDI options, and so never required much defending in arguments.

And yet, in retrospect, the fact that my Amiga devotion was more intellectual than emotional is part of its appeal. I certainly have nostalgic yearnings for it - the chug-chug-chunk of the floppy drive is a totemic sound second only to the Speccy's data screech in my mind - but when I look back on the best of the Amiga games library, it's with the safe and secure knowledge that they were genuinely great games, not just admirable efforts made wonderful by rose-tinted memory.

The Amiga may not have had the same technical limitations that forced 8-bit developers to be truly ingenious, but it had the muscle to drag gaming into new dimensions years before PC players gasped at Quake's solid 3D mazes.

Games like Stunt Car Racer, still one of the best and most original driving games ever made. Games like the weird little pixel sandbox of Robin Hood, the ambitious B-movie pastiche It Came From The Desert or the prototypical 3D open world rampage game, Hunter. Commodore was an American company, but it was UK developers who made it their own. Up in Scotland, DMA Designs and Lemmings. From Sheffield, Gremlin Graphics gave us Zool, the Amiga's unofficial platform game mascot, while Yorkshire neighbours Team 17 produced a run of amazing games that included Worms, but also Superfrog, Body Blows, Alien Breed and more. Perhaps the most iconic Amiga game of all, Sensible Soccer, came via Chelmsford's Sensible Software.

The Amiga is also worth remembering as the last truly dedicated games computer. Sure, you could get all the usual utilities and serious software packages, but the vast majority of owners bought one for the games. Not like today's PCs, which are home appliances which can also play games. Consoles didn't really take off in Britain until the SNES and Megadrive in the early 1990s, which gives the Amiga the feeling of a last hurrah of sorts.

By the time the Amiga's spotlight dimmed, unable to keep pace with the dedicated gaming hardware from Sega and Nintendo, its reputation damaged by the half-baked CD-32 spin-off console, it had done its job. It had guided UK gaming from flip-screens and pixel sprites into a world of solid 3D and rudimentary sandbox design. And, along the way, it had led me into a career which is still, somehow, going to this day.

It was a machine poised precariously, and perfectly, between two distinct eras of gaming. Those of us who were there to enjoy the moment will surely wish the ol' beige slab a happy 30th birthday.