The obscure baseball game that went on to be the PC's second highest ranked game

Unravelling the strange appeal of Out of the Park Baseball 2007.

It's the bottom of the ninth, the bases are loaded, and the Phillies need just two runs to clinch a spot in the World Series. But something's holding up play. Jim Skaalen, the pitching coach, and Jonny Estrada, the ninth batter, are arguing furiously as they approach the mound. Estrada, it seems, has lost faith in the abilities of his general manager. "I don't care if he's new to this, skip," Estrada objurgates, "he shouldn't have to Google what a 'bunt' is."

I've been playing Out of the Park Baseball 2007 for a few weeks now. It's a remarkable game in a number of ways. It's the brainchild of a German programmer, published by a British studio, yet embraced as one of the purest expressions of America's national sport. It's obstinately unwelcoming to newcomers - a sea of statistics and acronyms with nought but a 518-page manual to help keep you afloat - yet has seen its user base grow and grow. Oh, and there's the small fact that for the past nine years it's been listed as the second best PC game of all time on the internet's biggest review aggregator website.

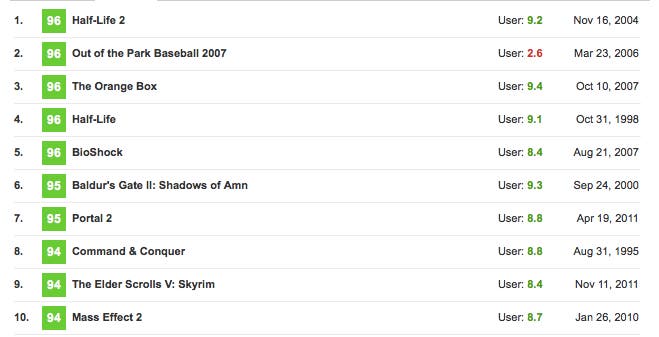

You've probably seen it there, on Metacritic, and assumed, like me, that there had been some kind of mistake. Especially once you take into account the company it keeps. With a 96 rating - the site's 2007 game of the year - it sits alongside Half-Life 2, Skyrim and Baldur's Gate 2. These are games that have become cultural touchpoints, so accepted into the gaming canon that they exist now more as memes as much as they do playable experiences. Out of the Park sticks out like a golden sombrero - a fact highlighted by its hundreds of scathing user reviews. A sampling:

"A MAJOR insult to PC gamers and Developers alike". "Did the critics get paid for writing the reviews or did the game developers just kidnap their whole family and hold a knife on their throats? Probably both." "One of the top 20 worst games ever made... on par with releasing a new Jaws movie."

Shark movies aside, the ire on display here is understandable. Using numbers to represent intangible things like opinions has always been a tricky business, especially when trying to compare experiences as disparate as sci-fi 3D shooting with text-based sports simulation. Out of the Park highlights the inherent absurdity in saying one experience is 1 per cent better than another, and for a user community built around deifying this very process, it's a disquieting anomaly.

There's another factor at play here, though, I think, and that's the feeling of alienation that comes from failing to enjoy a universally lauded game. It can be frustrating when something accepted as great seems beyond your appreciation and understanding. It's a feeling many of us will have felt in art galleries, at the theatre, or simply playing games from unfavoured genres. Might Out of the Park in fact deserve its revered status, if only the time was taken for it to be truly understood? It was this question that prompted my inglorious and brief career as a Major League Baseball coach.

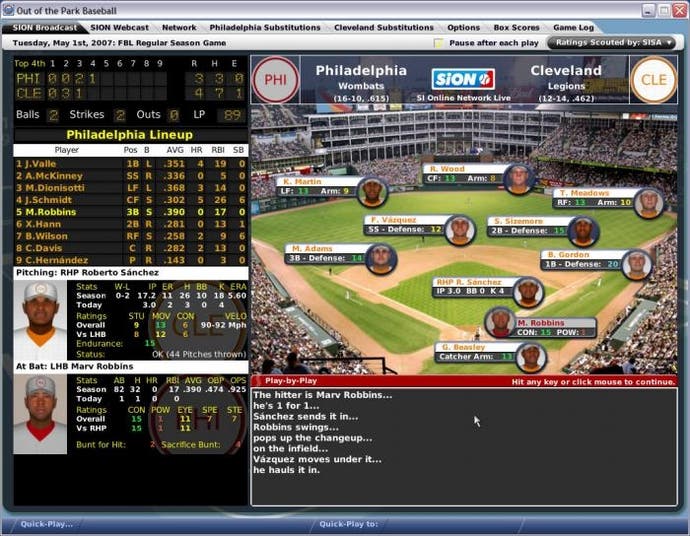

What struck me most, especially in the first few hours, was how much control Out of the Park granted. It's much more a simulator than, say, Football Manager, allowing you to alter all facets of the game world with little more than a right-click. Team names, player names, salaries, league structures - even player stats were free to alter. If you felt Ken Griffey Jr's running speed had been underestimated, you merely type in something higher. No-one's going to judge.

What this means is that the challenge comes not necessarily from creating a winning team, but from running one realistically and effectively - managing different personalities in the dressing room, negotiating contracts, maintaining a decent youth system. The games of baseball themselves are mere afterthoughts with results automatically generated unless you select to view them. Even then, you can only influence the action in a very limited fashion (such as opting to bunt, whatever that means).

Out of the Park is fantastically detailed and boasts a tremendously sophisticated AI, meaning that even with my rudimentary understanding of the sport I found myself drawn in as the season unfolded. But it wasn't a desire to win that compelled me forward - more a feeling of satisfaction in playing my part in this hugely complex story as it unfolded.

Delving into the game's online community seemed to echo these feelings. Rather than boast about achievements or offer tactical tips, much of the discussion seemed to focus on fictional leagues that created compelling narratives, or new ways to add further layers of detail, such as downloadable club badges and uniform packs.

Consider this discussion, for instance, on the pitfalls of running an 1890s league in the game's most recent iteration, or this on a fictional Pan-Asian League. Meanwhile, this thread sees forum members source pictures for the Negro League (disbanded in 1951).

The more I read, the more I played, the more I felt Out of the Park had been misunderstood, not just by Metacritic's community but by the site itself. Though there is a game here, it's buried so deep beneath layers of HR admin and fan fiction that it deserves to exist in a category completely separate from any other popular sports titles, let alone the likes of The Orange Box. If comparing Fifa and Dark Souls is apples and oranges, Out of the Park isn't even a fruit. I'm still not entirely sure it can even be classed as edible.

I reached out to Markus Heinsohn, the series creator, to find out a bit more about Metacritic's commercial impact on the game. He was understandably keen to underplay its role in his project's success, and I got the impression I perhaps wasn't the first person to treat his lifelong passion as if it were merely some kind of curio.

"I think it was about nine years ago that I first heard about it," he writes. At the time, "gamerankings.com was the bigger site" and a positive Metacritic rating didn't mean a great deal. But when the game was released on Steam, that infamous 96 per cent started to have a "real impact". "Potential customers could immediately see that it was a critically acclaimed product."

But what about its apparent misclassification, and the resulting online anger? Isn't it frustrating to see his game forced into such unfair comparisons? "The internet is full of jerks - why should I care what they say? Everyone is entitled to their opinion, whether or not it makes sense." Indeed.

I read Moneyball last year. The book, now also a film, explores the use of statistics in sport by following the Oakland Athletics' 2002 season, in which "undervalued" players were signed according to data modelling rather than traditional scouting. Baseball, the book concludes, is particularly suited to such reductive analysis.

Metacritic and its ilk has attempted to do the same with cultural criticism. And so it's somehow fitting that a baseball game - drawn from a sport which seems to share this desire to diminish human endeavour into a set of numbers - has been so problematic for it.

An endnote, before I return to Citizens Bank Park. While writing and researching this article, Out of the Park 2007 quietly dropped off Metacritic's best PC games page, where it had nestled awkwardly in the top three for almost nine years. I got in touch with the site's games editor, who explained that a seven-review minimum threshold had recently been introduced - eliminating Out of the Park, which only has five.

Given the timing of the change, shortly after I had made initial contact with the site about this article, I can't help but feel partly responsible. And so I hope you'll join me in clicking "Add Excluded" - an option carefully greyed out, resting innocuously above the user scores - and admire that glorious anomaly, one last time.