Monkey Island developer Ron Gilbert breaks down the funding of an indie game

"Seeing $500,000 in your bank account can make you cocky."

Monkey Island and The Cave creator Ron Gilbert has detailed the potential problems and possibilities of developing a game on an indie budget.

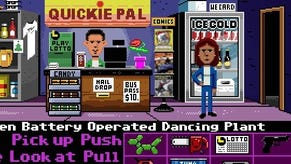

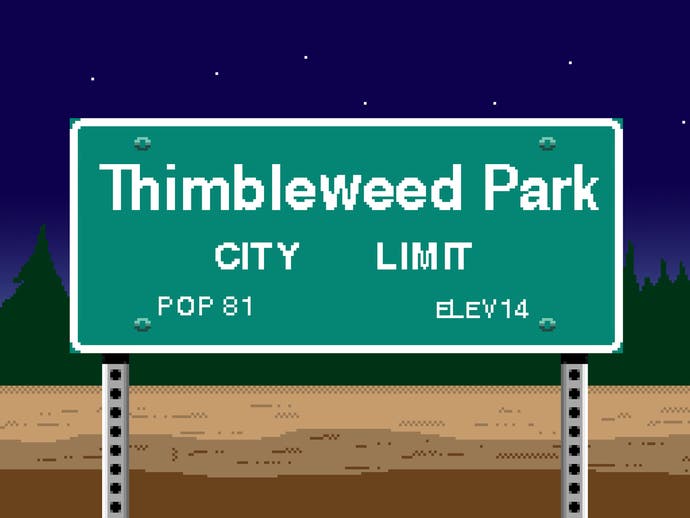

Specifically, Gilbert has discussed the funding of Thimbleweed Park, a point-and-click adventure funded via Kickstarter and due for release next year.

Thimbleweed Park's crowdfunding campaign raised $626,250 (before Kickstarter took its cut). Which seems like more than enough money to make a simple 2D adventure game. Right?

"Seeing $500,000 in your bank account can make you cocky." Gilbert wrote in a lengthy new blog post discussing the game's budget. "It can seem like an endless supply of cash and more money than most people (including me) have ever seen in their bank account.

"But you have to treat that $500,000 like it's $5,000 or even $500. Every dollar matters. It's why I like to have a budget."

Launching a game without a publisher has its advantages and disadvantages, Gilbert explained.

"One of the advantages of having a publisher [is] they will poke your budget full of holes and challenge your assumptions. The downside is, they will also push your budget down and it's not uncommon for developers to then fake the budget so they get the deal (which their studio is often dependent on to stay alive).

"It's not malicious, they (and I have done this as well) just convince themselves they can make it for less, and that's often not true."

Budgets were especially important as an indie developer, he continued, as there was no one to fall back upon for more money if the project became too costly.

"We had budgets back at Lucasfilm, but we were very isolated from the gory ramifications of those numbers. I could make a budget and if I went over by 20 per cent, I might get a stern talking to, but it's not like people weren't going to be paid.

"When you're running your own company and project with your own money and you run out, people don't get paid and they don't like that. In the real world, they stop working."

So, you have a budget. What are your main expenses? Well, firstly you have the people employed to make your game. Turns out, paying them is important.

"Gary [Winnick, long-time collaborator and fellow Thimbleweed Park developer] and I are working for peanuts (honey roasted)," Gilbert wrote.

"Neither of us can afford to work for free for 18 months and we're making about a quarter of what we could get with 'real jobs' but we do need to eat and pay rent.

"Everyone else is working below what they could get, but I do think it's important to pay people. I don't feel getting people to work for free ever works out and usually ends badly (and friendships) or you 'get what you pay for'.

"The reality is that when someone works for you for free, you aren't their top priority. They may say you are, they may want you to be, but you rarely are and you end up dealing with missed deadlines and hastily done work."

When the game is nearing completion you will also need testers, Gilbert continued. It's a cost that some developers try to avoid, but doing so may often end up costing more down the line.

"Testers, testers, testers. One of the most important and often forgotten roles in a game. It's money well spent because not testing will cost you down the road in emergency patches, dissatisfied players and crappy review scores."

Music and sound effects will also cost you money. Composers charge by the minute of completed music but will usually complete the work quicker than amateur musicians offering their work for free.

"If you're going to have 15 minutes of unique music and they charge $1,000 a minute (not uncommon), then your budget is $15,000," Gilber explained. "[But] that $1,000/minute includes a lot of exploration and revisions and mixing.

"If you're saying "Hey, I'll do your music for free" you need to ask yourself if you're willing to spend weeks exploring different styles and tracks while getting constant feedback, then spend months composing it all, then additional months of making little revisions and changes, then producing three, four or five flawless mixes."

An indie game's budget will likely also include travel and fees to showcase at events - places such as PAX and E3. This is an easy place to cut funds if the project is over budget, Gilbert wrote, because although it hurts sales it would hurt the game more if it launched unfinished.

Then there's translation, voice recording, mobile support, legal, accounting and software.

"Assuming we don't get sued, these are fairly predictable and fixed expenses," Gilbert concluded, "but don't forget them.

"This is how games are made, they take time, cost money and it's a very messy process."