Prison Architect review

Shawshank retention.

Editor's note: Prison Architect releases on consoles this week, and to mark the occasion we're returning to our original review of the game, first published last October. Double Eleven has handled the console versions, introducing a new introductory Prison Warden mode with ready-made prisons, as well as featuring a mode that lets you share and play other people's prisons.

If I have one tip for you, it's that you should get dogs.

Dogs are wonderfully versatile. They do an excellent job of sniffing out contraband hidden in whatever crevices prisoners hide contraband in, they quickly find the tunnels inmates have been slowly scratching out and they chase down escapees like furry homing missiles.

But in discovering all those smuggled drugs, in revealing those hidden tunnels, those dogs also make your life more complicated. In Introversion's prison management game, which has just emerged from a long spell in Early Access, the more you know about what goes on in your prison the more unhappy you'll be - and, likely, the more unhappy your inmates will be. Before I started revealing their secret vices, before I was able to clamp down on their bad behaviour, running my prison wasn't too difficult. Now, inmates riot. They fight in the shower. A man overdosed in his cell. I was a happier warden when I was an ignorant one.

Prison Architect's greatest strength is the freedom it gives you in denying others theirs. While there is an entertaining campaign to play through, which will teach you first the basics and later the nuances of prison administration, the real soul of this game is found in the blank canvas of correction it lays out for you. If your vision of a prison is a vast, brutalist hellscape that occupies every inch of available land, you can make that happen. If you'd prefer a modest and manicured minimum-security facility, somewhere where things never get nasty, drag a few sliders to keep out undesirables and hire a gardener. The world is your oyster and it's up to you how cruelly and tightly it closes.

The fundamentals are simple: your prison is compulsory lodging. None of your guests want to be there and some distant authority is paying their rent. The more you accommodate, the more money you make. Dangerous lodgers are more valuable but, as you might imagine, more inclined to disrupt or attempt escape from the confines of the Hotel California you have created. You may or may not be be concerned with comfort levels, re-education programmes or cleanliness but, first and foremost, you care about profit.

Your most basic employees are guards and construction staff, the former shuttling prisoners to and fro or providing pugilist persuasion to anyone who has delusions of liberty. The latter are your worker ants, scurrying about your compound as you demand more fences, plan out new a new wing or decide that, yes, your inmates really do deserve a common room with all the luxury of a pool table and television set.

You'll need to watch those folks carefully, as they have a curious habit of performing their tasks in unusual orders. This can include building every segment of a sewage pipe bar one before moving onto a completely different task, or pathing slowly and clumsily around a building to try to finish the last section of a security fence. Most of the time, they can be relied upon, but occasionally they need a firm hand, not least because their work is as critical as anyone else's.

So much of Prison Architect is about construction. It's about planning, about environment and about layout, all of which affect safety, security and reliability. Every prisoner may have their personality, but the prison itself is always the central character, the locus around and through which everything else happens.

This is because every construction choice matters. This isn't Sim City, where some neighbourhoods end up trashier than others, or where a quick bulldozing fixes an infrastructure imperfection. Prison Architect's ecosystem is far tighter, far more sensitive, with budgets that aren't sympathetic to constant demolition or rearrangement, and then there are the penalties for incompetence. Poor judgement calls can have you face a fine or, depending on your difficulty level, a firing.

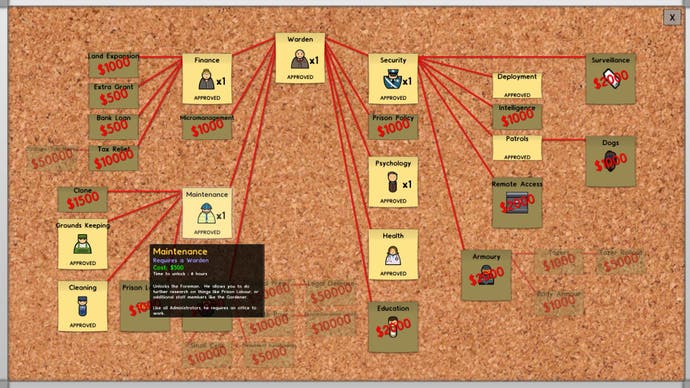

Prisoners are canny, too. They dig. They demand visitors, then ask relatives to smuggle items in. They find just the right moment to attack a rival gang member. They find the path of least resistance and exploit it constantly, doing something you might not realise for hours, even days of game time. It's all that you can do to gradually unlock and employ an ever-growing team of experts who will give you greater insight into their criminal minds, greater control over the deployment of a growing roster of guards and, sometimes, greater possibilities for the redemption of at least a few of these reprobates.

If my admiration isn't yet clear, Prison Architect is marvellous. It's one of the best management games in a long time, lean and focused. It's one in which, even with so many moving parts, everything that happens originates from a choice you made, a decision about layout or about policy. It's also one of the most stylish, most idiosyncratic games in its genre. The flat, cartoonish design, with its bold lines and broad caricatures, is a disarming facade behind which so many cogs turn. These flat characters are enough to make you forget the two-dimensional projection of your world: you will never build upwards.

A devil chuckles within the details, too. Little things, such as the buzz of a dot matrix printer as you issue patrol orders, or the endless moping of a handler who has lost their dog, add tiny touches of humour. Prison Architect doesn't reach for the big laughs, but the subtle smirks, another hint of the depths within.

And it takes time to reveal those depths. Getting your first functional prison up and running reliably may take you a couple of goes and some generous grants (extra funds which, thankfully, also provide direction for new players), but getting a really good prison going demands a very particular kind of diligence.

Unlocking staff like security chiefs and psychologists also unlocks more of the game's layers, revealing inmates' hidden desires, allowing for elaborate CCTV systems or presenting possibilities like prison labour programmes. This new information inevitably reveals new ways in which you're doing your job wrong, new ways in which you're falling short or failing those within your care. Again, your attitude to this will reflect just how much of that care you have, and the remarkable thing about Prison Architect is how it doesn't push you toward any sort of glamorous ideal, it doesn't reward any particular sort of prison or approach to play.

No, it simply presents a collection of agents acting within a series of systems and lets you frame, manipulate and exploit these however you choose. If you can make a lot of money running a grotty, cynical institution where riots are contained and beatings are commonplace, why strive for better? If your shining chapel and stuffed classrooms give you a sanctimonious sense of self-satisfaction, so be it.

Similarly, it's your choice if you wish to micromanage such details as your inmates' meal times, remote-controlled security doors or cell allocation. You certainly can - and I found it practical to carefully separate the times at which different prisoners ate - but this is a game that, to its credit, can be thoroughly enjoyed without peering too closely at the fine print.

In the far longer term, Prison Architect loses a little of its edge. The staff technology tree means prisons tend to evolve in a similar fashion and, after assembling a couple of capable prisons, you will have seen most of what the game has to offer. However, the ability to sell a prison and put its funds toward another, effectively approaching a new game with a substantial head start, is a fine idea. It means you can immediately begin again on a greater scale, rushing through the rudiments toward greater things, the game eating yet more and more of your hours (and so many of mine have slid down into its ever-growing stomach).

A little more disappointing is how the game's depths are not always apparent. These prisoners really are pushed, filed, stamped, indexed, briefed, debriefed, or numbered, dehumanised by the systems they find themselves inside, but the finer details or their character or motivations are not always as obvious as they could and should be. There's an argument for this being perfectly reasonable, since any diligent warden should be proactive in investigating and understanding their clientele, but in a thronging prison of so much cause and consequence, this is a lot to ask. The whys and the wherefores could be clearer and a few more tooltips or reports wouldn't go amiss.

But I have few complaints. So few complaints. For years now, players have watched Prison Architect mature through a sometimes very bumpy Early Access evolution and now it has come of age, blossoming into a beautiful new management game marred only by what are, at their very worst, a mere scattering of pimples. It's smart, it's challenging, it's even a commentary on incarceration and reform in a capitalist culture. Go on. Get some dogs.