Storytelling in Mankind Divided: Choice, consequence and cynicism

How to build a future that falls apart.

"The future is the same, but different." It's a phrase I've heard oft repeated and yet never attributed. Whatever its origin, it suits Eidos Montréal's vision for Mankind Divided very well indeed. Not only do the team want to continue to serve us their very particular flavour or cyberpunk cynicism, showing a world where technology has created as many problems as it has solved, they also don't want to alienate players who so enjoyed Human Revolution. "You don't have to reinvent the wheel every time," is producer Olivier Proulx's philosophy.

"History does not repeat itself, but it rhymes," is a quote attributed to Mark Twain, though no actual origin can be found. It's appropriate not only because Eidos hopes that Mankind Divided will be very much in accord with its predecessor, both echoing and building upon its themes of disillusionment, flawed technology and conspiracy, but also because it relishes the idea of making so much opaque and uncertain. Dark and shadowy forces are at work behind the scenes, manipulating events on a global scale, while truth itself is a malleable, even servile thing. Nothing is clear and, in this game all about consequence, the road to hell is paved with good intentions.

Plus ça change, I think, as I make my return to Deus Ex.

My first impression is one of surprise, as so much about Mankind Divided feels very, very similar to Human Revolution, so much so that I wonder if Eidos have been timid about tinkering with something that has been such a big success. Creeping, hacking and blasting my way through two demonstration levels, I know exactly what's expected of me. The patient, non-lethal approach works for a certain kind of play. A crafty, gadget-wielding philosophy cuts all sorts of corners and gunplay, of course, brings all the boys to the yard, but it also kills them in the yard. And then lets you drag all their bodies into one a big pile in the yard, since subtlety clearly isn't your bag.

"You have to keep the DNA of a Deus Ex game," Proulx tells me, describing Mankind Divided as a well-considered evolution which doesn't intend to introduce a raft of new concepts or mechanics, instead presenting players with a deeper, more complex plot. There are many subtle advancements to be found, but what Eidos seems most invested in is telling a grander, grittier story with greater player choice. And telling it as well as they can.

"Early on we decided that we were going to be back with Adam Jensen," Proulx continues. "He's interesting to us because he's an outcast to everyone, both to 'naturals,' because he's augmented, but also to the augmented population, since Adam is the next level. He doesn't need Neuropozyne [the drug that prevents the body from rejecting augmentations] to sustain himself." Jensen is the perfect blank slate for players to project themselves onto, as he starts with few firm loyalties or affiliations and also experiences so many of the imperfections and alienations of his world.

However, this isn't the same Jensen who "never asked for this," in Human Revolution. Eidos is calling him "Jensen 2.0," a more confident, more assured man who, two years on, is more comfortable with who he is, more capable and better augmented than ever.

The rest of the world, however, is not doing nearly so well. After the Aug Incident of the previous game, in which countless augmented humans were driven insane by malicious manipulation of their augmentations, there's widespread distrust, even outright prejudice toward anyone augmented. "We really doubled down on what happens with that, with the theme of people being scared of what they don't know or understand." Proulx says. "We thought that this was a very strong and, unfortunately, universal theme, that of segregation and of the fear of what's different."

Continuing the plot and themes of Human Revolution doesn't bring the game that much closer to the dystopia of the original Deus Ex, but this isn't something the team are too concerned about. They want to write their own stories, rather than serve those of others and at a round table discussion, narrative designer Mary DeMarle offers a very simple solution to the problem of storytelling conflicts.

"History is written by the winners," she says. "What we 'know' in [20]52 [the year Deus Ex is set], we know in '52, but that might not actually be how it happened. We're looking at the original plot and finding ways we can reinvent it and pull it forward." It's entirely appropriate, she says, that things may not match up, even that the history recorded in Deus Ex is inaccurate, especially as much of Mankind Divided will be about "dealing with what is truth and what is not truth. Who can I believe? Who can I trust?"

As the team describe how much time has been invested in narrative development, they paint a picture of a game where choice and consequence are more important than ever, but also hopefully much more subtle in their implementation. While the player's decisions, moral, practical or whimsical, will shape and mould the story, the idea is to repeatedly surprise them with unforeseen (and even unpleasant) outcomes, to make apparently simple choices profoundly significant later on and, critically, to avoid leaving the biggest decisions to the very last moment.

"Great as Human Revolution's story arc was, you get to the end and you can just play with your saved game to choose one of the four endings," says Proulx. "This time, we wondered, what if a few of the choices you made in the first hours of the game could impact what happens at the end?"

Similarly, the team say they're also working hard to make side quests feel more like they're an important part of the narrative, a parallel experience rather than a contrived tangent. "Adam Jensen is out to save the world," says DeMarle. "Or at least he's always on a serious mission. Anything that pulls him out of that has to have weight. It has to reflect the themes of the game or maybe shed light on the factions or characters of the game."

"I hate 'side quests,'" adds gameplay director Patrick, who has no interest in having players running fetch quests or wasting time that should be valuable to their character. "Now, for players, they might not even know they're on a side quest. It'll feel like a main quest." The idea is to always make the mechanics of the storytelling far less transparent. What exactly is a side quest? What even is a big decision? What exactly are you getting yourself into? "You're never sure as a player," he continues. "You have to think about what you're doing before you do it. You even have to make sure you're comfortable with your line of action."

The team are excited to talk about all aspects of narrative and also world-building, clearly having invested a great deal of their time and energy in creating what they hope will be a coherent, believable and perfectly imperfect vision of the future. In an interview, Proulx describes an unusual conceptual phase where a great deal of the game was planned out "on paper" long before other production began. They didn't want to run before they could walk.

"The peaks and valleys of the narrative, the beats, the main themes, the different locations. We wanted to lock these down pretty early in production," he says. "We prefer to do it on paper for a few months, in a meeting room, rather than later in production when we have all these concept artists, level designer, VFX artists and people who need something that's set in stone."

Much of the development process has been something Fortier describes as collaborative and "collegiate," with artists, writers and level designers all encouraged to contribute, not least because one person's suggestion might affect the the work of several others. "Everyone is serving each other," he says. "If there are things we want to do in the level design, they have to be justified narratively. Narrative goals have to be justified in the gameplay. We talk things through, everybody brings something to the table and the game grows organically out of that." It not only makes room for more contributions, but makes the whole team feel invested in what they are creating.

"After HR, the team had a lot of ideas about what they wanted to do," he continues. "The narrative team wanted to push the choice and consequence angle a lot more, also in the minute-to-minute moments and not just in the big story arcs. The level design team wanted to explore more verticality. The design team wanted to see what we could do with the cover system."

And that returns us to a discussion of the subtle changes in Mankind Divided. Thankfully, the new cover system feels straightforward and simple. With the push of a button, a third-person view gives a little more situational awareness, allowing Jensen to peek out and even fire from hiding, but otherwise remain unseen. It also highlights nearby cover that he can make a quick dash for. However, Jensen hasn't suddenly found himself in a third-person shooter, moving in and out of safety with the push of a button, and both movement and stealth still maintain a loose, organic feel. The changes merely serve to present more perspective and opportunity.

There's also an elaborate but efficient interface, with which Fortier is particularly pleased. Snappy menus allow augmentations and weapons to be quickly selected, assigned or reassigned, inventory to be ordered and tools to be used with the press of just one or two buttons. It's not the most dramatic of improvements, but it allows the game to present complexity without inviting confusion. Similarly, behind the scenes the Glacier 2 engine, which powers the latest Hitman, has been modified to support the dense environments that the game demands. "We wanted an engine that was going to be able to render a lot of objects," says Fortier. "We have a lot in our maps and we use that density partly as a storytelling device."

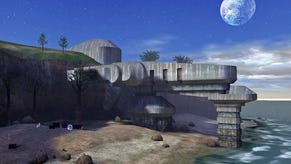

But while Eidos will talk about technical improvements, their new lighting system or the merits of controlling their post-rendering effects, what they return to again and again is plot, theme and the sort of complex, shady and morally ambiguous stories they want to plunge their players into. They're cagey when it comes to detailing exactly where the game will take players, but the demo levels were set in Prague, an old city festooned with new technology (giving it a Dunwall-esque vibe) and a devastated Dubai.

The latter feels particularly inspired and Eidos' depiction of a shining city in the desert that has fallen into decay, its augmented workers suffering, it's half-finished hotels open to the elements, feels almost prophetic. "Dubai isn't really what you think about when you think about cyberpunk and Deus Ex," says Proulx, "But the more we considered it, that contrast of the new money, those shiny buildings..."

Wherever Jensen's adventures will take him, Proulx insists that he will find difficult choices, unintended consequences and, sometimes, very unpleasant truths. This time around, Eidos is hoping not just to present players with those same elaborate locations that can be solved through a variety of approaches, but also to offer them equally elaborate plots that offer more narrative freedom. At the same time, the team also say they'll be making no judgements as players navigate the morally grey world they've had so much fun building for them.

"We don't have a meter in the game that says if you're good or evil," says DeMarle "You make your choices, you see the impact in the game and that's it. The aspect that's critical to us is to get the player to choose."

"And to live with the consequence," she adds.