Yakuza 5 review

Shenmue's true heir.

Despite a cast composed largely of gangsters, and a plot centring on the machinations of various families, Yakuza 5 is not by any stretch of the imagination a game about organised crime. Oh it's dressed up like that, and amidst battling endless thugs and police officers you could be forgiven for the mistake. But really Yakuza 5 is really a game about saving puppies, obeying traffic laws, and losing yourself in hobbies.

The first two Yakuza games, released for PS2, established the series as - in my mind - the more hard-edged successor to Shenmue. Original director and now series producer Toshihiro Nagoshi took the structure of Yu Suzuki's masterpiece, the small-but-dense style of open-world design, and layered atop it a more mainstream theme and a much more detailed, dynamic combat system. The connection between the two games is at its strongest in what you actually end up doing as Kazuma Kiryu or the four other lead characters - which is to say, anything other than progressing the main plotline.

The first few hours of Yakuza 5 are more or less an avalanche of minigames and side-quests, with the player shuttled forwards through the basics before being left (relatively) free to explore the opening town of Fukuoka. It's worth pausing, though, over exactly what kind of open-world this is. Yakuza 5's locations are compact but detail-rich places, where you can run end-to-end in a minute or two but spend hours walking the same distance. Everything is about density rather than scale. Kazuma Kiryu isn't the fourth chairman of the Tojo Clan, for me, so much as Ryo Hazuki's true heir.

This is all great but a more unusual technique is the constant use of location-switches and loading screens for side-quests - the progression is typically 'walk down street, talk to stranger, accept mission, loading screen.' Yakuza 5 is able to be so freeform in its sidequests and objectives because they're bubbled like this, and the whole thing is stitched-together rather than seamless.

This is the opposite of 'normal' open-world design, which aspires to smooth transitions between roaming and quests, but here it's perfect. The number and variety of sidequests means that picking them up then running to a 'start' location would rapidly dull the appeal, and the jumps also contribute to a major part of Yakuza's charm as an experience - you never know where you'll end up after talking to a random stranger. The sidequests retain their appeal not just through quality but by constantly surprising you, whether that's with a new mechanic - many of which are introduced, toyed with, and then open up their own quest tree - or a comedy scenario, or a salty conversation about gamers wasting their time.

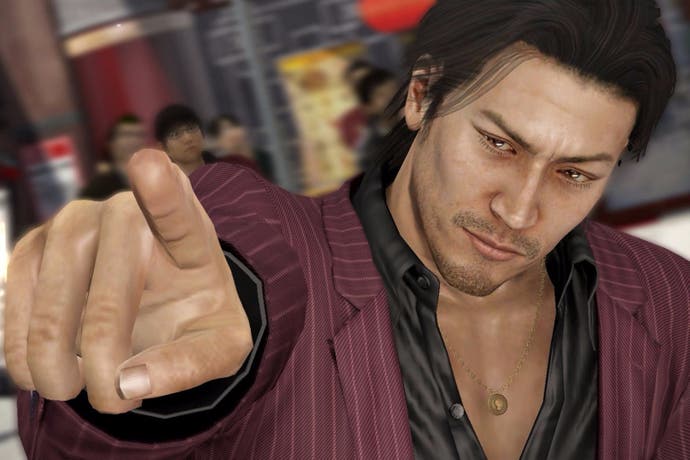

Roaming each of the five towns is still possible, of course, though you'll often have to engage in combat with random street gangs while doing so. The fighting system is a loose style of arena brawling (civilians create a 'ring' on open streets) that gains much of its impact from the context-sensitive 'heat' system. Normal attacks throw out a quick combo, but triggering 'heat' at certain points opens up a whole new universe of goon-shattering moves that are executed with maximum brutality. I'm not kidding about the last part: an early move you unlock with Kiryu involves grabbing a facedown opponent's head, then scraping it back and forth across the concrete before a slam. Suplex someone and you'll see their head compress into the shoulders as a cloud of blood puffs from the mouth.

That's not the half of it - the heat system can be triggered using almost anything, in any situation, and it's nearly always funny. If you're next to water, or a roof, you might starting theatrically tossing people over the edge. If you're holding a glass table, it'll be smashed right over some luckless goon's head which seems to squash into his shoulders from the impact. Many heat moves even feature QTE follow-ups which pile on the punishment, and the camera angles on stuff like Kiryu's headbutt are hilarious. There's something about the unexpressive faces of video game characters in the midst of ultraviolence that just tickles me.

One problem is that it takes a while to unlock the complete moveset and, unless you're taking your time about exploring, you might not find key techniques. But once the generous level curves kick in and the characters start acquiring offense for nearly every situation, you're positively throwing yourself at thugs - and very few can take it. There are great fights in Yakuza 5, mainly against 'boss' characters, but by far the biggest aim with the combat is making the player feel good about themselves. You'll almost never lose a fight outside of the bosses, as long as you've got a few (easily-acquired) health items, but at the same time winning feels so great this minor detail hardly matters.

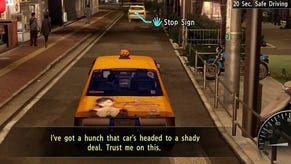

In the combat, as in all things, Yakuza 5's instinct is towards generosity. This is why I spent an inordinate amount of my time driving a taxi around Fukuoka, and if you're thinking this is a Crazy Taxi tribute you couldn't be more wrong - it goes the other way. There are an enormous number of taxi missions for Kiryu, each with an individual passenger with their own destination and preferences, and everything is about driving 'properly.'

So accelerating too fast is a no-no, as is turning without an indicator. Running a red light is unthinkable, while colliding with a pedestrian is so far out that you're soft-reset on the road. On top of this the passenger will be making small talk, which you have to choose the 'best' answers to, and there are all manner of minor distractions on the road. This isn't a simulation, really, but it's leaning in that direction and somehow works beautifully. It's the limits, I think. So many open-world games give you a vehicle and let you go nuts, but here you're acting in a professional manner - which is the job - while responding to increasingly off-the-wall customers and demands. That balance meant I spent almost a whole day just wiring through these missions, and it gets even better - your 'driving skill' feeds into pimping-out your taxi, which can also be used for an excellent series of races.

Whatever I expected from Yakuza 5, it wasn't to become obsessed with taxi missions, but that is this game writ large - exploring becomes so compulsive because you just keep on finding amazing diversions like this. The game offers five cities and five characters in total and, though I eventually had to start rushing through the main questline, all have these character-bespoke minigames that bloom into something larger - like Haruka, a longtime support character, whose section replaces the combat system with 'dance-offs' that are probably more challenging.

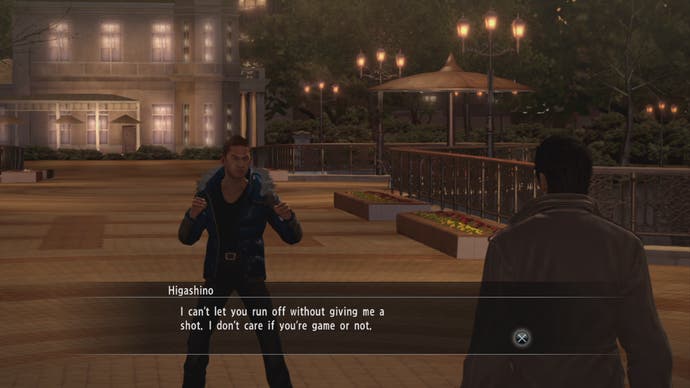

In this paradoxical world, where hardened criminals are the real social heroes, the script is another of these oddities. The plot is obviously ludicrous - the game begins with Kazuma Kiryu, who established the Tojo Clan as the greatest ever clan in previous games, now eking out a living as a taxi driver in Fukuoka, which of course then becomes the nexus for all organised crime in Japan. Within this structure, individual scenes are well-written and directed. But all the spoken stuff and rendered cutscenes are just a coathanger for the real meat, which is the text dialogue.

Walking through Yakuza 5's towns, you will overhear snippets of conversation - some of which alert you to potential sidequests. But these worlds are also full of incidental characters with much more to say, their own little quest arcs to explore, and it's where Yakuza 5's script really takes off. This is a wonderful localisation: frank, funny, and jam-packed with little human surprises.

One of the subterranean appeals of Yakuza is the link between director Nagoshi and some of the distractions on offer, and particularly the food and drink. Settling down for a refreshment in Yakuza is like a miniature education, with the text and characters going into detail about the ingredients, manufacturer, and the sensation of eating or drinking it. Nagoshi lives the Japanese high-life and is something of a gourmand, in an obvious sense Yakuza is a reflection of that, and this aspect of the game feels almost intimate - like enjoying a good whiskey with a friend after a hard day.

Intentional fallacy or no, this window into modern Japanese life is a big part of the Yakuza appeal. Personally I've always had an outsider's fascination with Japanese culture, have visited it a few times, and so find these languorous digressions into the minutiae of beers and noodle dishes fascinating. So much of Yakuza's world is bound-up in this kind of detail that it inspires odd playing habits - I always go and get a drink before bed, just for the factoids and chat with the bartender.

The seedier side of this is the hostess bars, where you can go and 'romance' various young ladies by buying expensive drinks, gifts, and giving the right answers in conversations. I've never seen the appeal in virtual dating games, and Yakuza's certainly don't change that: the rudimentary logic of 'cash = love' doesn't seem especially interesting, and the couple of conversations I had were just bland feel good stuff about "believing in yourself" and so on. It's impossible not to notice this side of Yakuza, because clearly a lot of time has been spent on it, but easy enough to ignore. Of all the aspects of Japanese culture that the game highlights, this feels like the one most lost in translation.

Yakuza 5 is such an enormous, generous game that it can afford sections like this - because if it's not your thing, there's still hundreds upon hundreds of hours elsewhere. My save file is now just over 30 hours and it feels like barely scratching the surface - even if I did spend lots of time in a taxi, or playing Virtua Fighter 2. This is a world of endless, delightful distractions that keep feeding into one another. It's amazing enough to find a (limited) version of Taiko: Drum Master in the local Club Sega, but after exhausting that you can just head down the street to a karaoke bar - and play Sega's twist on the same, tailored for pad controls, while characters belt out some Jpop classics.

This is the kind of game you get from an experienced development team that knows what they're making. Yakuza 5 is all about refining what was already a great series, and delivering the ultimate version of it. There's just so much of it to do and, unlike many 'content-rich' games, almost none of it feels like filler. You can go hunting and fishing, play baseball or golf, darts or pachinko, take on NPCs at Shogi or Mahjong, cook noodles, have snowball fights, dabble in chicken racing or flutter it all away at the casino. It's an imaginary world of such richness that, once you're in, the Yakuza are the least interesting thing about it.