Gravity Rush Remastered review

Upside down, inside out, round and round.

This might seem an odd thing to write, but Bluepoint Games is currently one of my favourite developers. You can bemoan the circumstances that this Austin, Texas remaster specialist is profiting from - the holes that, two years in, continue to gape in Sony's internal game production schedule for PlayStation 4, with multiple major projects canned or writhing in development hell - but you cannot argue with the work.

With their crisp visual fidelity, flawless performance, fine detailing and careful attention to usability, Bluepoint remasters are as polished and easy to enjoy as any game software out there, up to and including the work of Nintendo's in-house teams. More than that, Bluepoint know how to do justice to their source material while letting it breathe - sometimes, arguably, better than the original creators managed. (Its Xbox 360 version of Titanfall must be the only port to older hardware to attract controversy for being too good.) Bluepoint's developers know exactly when to tweak or update, and when to leave well alone. They're keeping great games on the shelf on new systems, showing their best side and being themselves.

Gravity Rush Remastered, which Bluepoint produced alongside last year's superlative three-game Uncharted anthology, is a smaller-scale but still considerable challenge. Sony Japan Studio's weird and mostly wonderful steampunk fantasy was an early Vita game, so it has had to be made to work in a new, less intimate context. It has to be stood on its own two feet when it was originally locked in a tight embrace with its host hardware - Gravity Rush was something of a showcase for Sony's lofty and ultimately doomed ambitions towards expansive, visually rich portable gaming. And it's a strange, almost deliberately discombobulating game to start with. In other words, Gravity Rush is an awkward customer.

Bluepoint has done its usual brilliant job, which works for and against Gravity Rush, bringing both its strengths and weaknesses into focus. I'm going to turn my attention to the game itself now, but for more on the technical specifications and tweaks of this new version, please check out Digital Foundry's analysis.

Gravity Rush was called Gravity Daze in Japan, and both titles work. The Western name emphasises the heady thrill of the gravity-manipulation mechanic that allows our young heroine Kat to fly, or rather, fall pell-mell around the green skies and grey gothic brickwork of its floating metropolis, Hekseville. The Japanese title suggests wiggy disorientation, evokes the game's surreal, dreamlike air, and also hints at the (largely unresolved) mysteries of its intriguing setting and garbled plotting. (According to Wikipedia, the full thing translates as "Gravitational Dizziness: The Perturbation of Her Inner Space Caused by the Repatriation of the Upper Stratum").

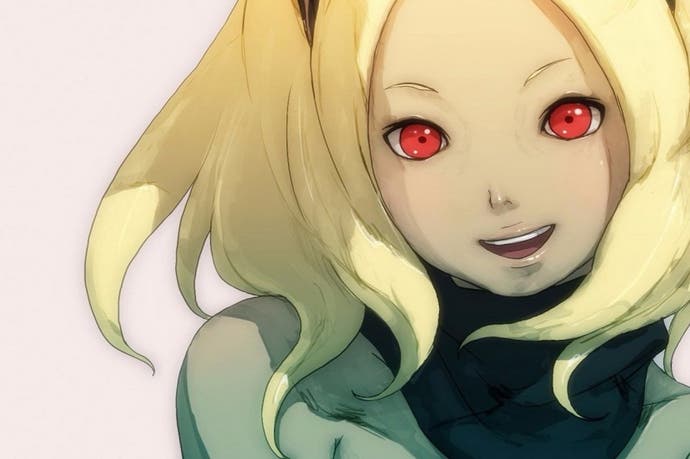

Kat falls into Hekseville as an amnesiac young woman, accompanied by some sort of astral cat she calls Dusty, who by his presence grants her the power to put the force of gravity where she wants it and tumble wildly through the air to her destination. Confused, cheerful and curious, Kat is a winning creation. She reacts quite blithely to her haphazard and preposterous escapades, which involve invading gelatinous creatures called the Nevi, a strange old man who calls himself a Creator and opens doors to other worlds for her, a notorious thief, and some kind of intrigue in the city government. Big stuff, but she's more bothered about making friends and finding her place in the world. And though she's a cutie in a regulation superhero leotard, she's no prim princess: the artists and animators give her a wonderfully untidy and violent energy as she flops, tumbles and crashes around, using her newfound power with more enthusiasm than grace. With her cat companion, unruly flying skills and fragile but fierce adolescent will, she reminds me strongly of the young witch heroine of Hayao Miyazaki's classic animated film Kiki's Delivery Service. (Miyazaki wouldn't have given you the option to dress his lead up in sexy maid and schoolgirl outfits, mind.)

The game's director Keiichiro Toyama, of Silent Hill fame, has meanwhile cited Moebius as an inspiration, and you certainly see the great French comic artist's weightless surrealism, along with many other influences, in the work of Yoshiaki Yamaguchi's art team. Hekseville is a memorable creation, a sort of pocket universe trapped in an alternate belle époque of stubby air-taxis, neo-gothic architecture, pleasant gardens and smoky industry, but not without an underside in the tangle of sub-streets where the poor fight to find a place to stay. (Kat seems perfectly delighted to make her home in a drainpipe.) Humorous and whimsical, the characters and setting come across best in the lively comic-book cut-scenes. Though Bluepoint has done its best to embellish them, the city district maps have a slightly basic, claustrophobic look that betrays their handheld origins, while excursions into other dimensions and the deep roots of the world settle for a rudimentary abstraction that draws some of the game's strong personality away.

From a gameplay perspective, Gravity Rush is all about Kat's "shifting" gravity ability, which still feels fresh four years on. At first it's a freshness of the awkwardly unfamiliar kind: you need to upgrade Kat's skills by collecting gems to get it to really sing, the camera sometimes struggles to keep up, and you'll be into the game's second act by the time you feel comfortable enough to use it fluidly.

The controls are perfectly intuitive though - Bluepoint did well to bring gyroscopic motion-control aiming across from Vita to the Dual Shock 4 - and Kat's homing gravity kick is particularly satisfying to use in combat. Although she can use shifting to run up walls and across ceilings, the game doesn't play around that much with the potential of these perspective shifts for puzzles or head-spinning navigational challenges, which seems like a waste. Shifting is more about simple movement: a weird, intoxicating and powerful way to get around. So, Gravity Rush is more Jet Set Radio than Super Mario Galaxy.

In fact, seen in the harsh light of four years' hindsight and its new context on the big screen, it's more evident that the great imaginative force of Gravity Rush's conception isn't really matched by imagination in its execution. Its chief failing is some insipid and clunky mission design that was easier to overlook when we were dazzled just to be playing a game like this on a handheld console in the first place.

At best, the game's levels - whether story episodes, challenge missions or side quests about Kat's day job as a maid - are fun concepts made from very rudimentary building blocks: pockets of combat and checkpoint dashes. At worst, the concepts themselves are just as uninspired. The sheer fun of interacting with Gravity Rush's world keeps you going, and even when the game grinds you down with enemy spam or by arbitrarily restricting your powers, or the camera finally gets the better of you, it usually gives you just enough elbow room to keep frustration at bay.

For all of its novelty and immense charm, there are times when Gravity Rush feels like it's a lot more than four years old, and for all of its polish - especially in this exquisite new edition - there are times when it feels half-realised. The mildly paradoxically good news, then, is that this genuine one-off is getting exactly what it really needs: a sequel.