Superhot review

This is not an .exe.

Turns out there is a killer trick to creating hyper-violent entertainment: do the slow stuff fast, and the fast stuff slow.

That's literature right there. And cinema. Someone doing crucial research into a baddie's tax affairs, or the ballistics analysis on a bullet lodged in cartilage? Montage, I reckon. Or handle it over the phone. "Give me the highlights, doc." "In English, professor?" Someone getting a load of buckshot through the head, however? Ease into that one. Approach at glacier speed, alive to the possibilities. The finger tightening on the trigger. The matter leaving the barrel. The nimbus of gases. The compression wave cast through the air.

I read about this trick recently in a book about the author of the Jack Reacher novels, and then I saw it implemented - and gloriously so - in Superhot, a first-person shooter in which time only moves when you do. That's it, basically. The whole thing. You're not quite the writer or director, as these scenarios are very tightly defined from the off, but you are the choreographer. And, as is often the case, you are choreographing a very specific kind of dance. The dance of slaughter. Sulphur and bone-fragments. The triumphant crescendo afforded by a popping of the human skull.

It's magnificent. I never saw a game with such a smirking sense of its own potency. One by one you are dropped into hard-nut set-pieces: a stick-up in an elevator, a truck charging down an alleyway, a man who's just itching to be chucked out of a window. There's generally about ten seconds' worth of action here, but remember: time moves only when you do. The fast stuff is slow. So you move to the left - no good, a bullet to the head from an unseen assailant. Restart. You move to the right. the bullet whizzes past your ear. Now to the left, as the guy who fired reloads. A punch? One two three and he's crumpled. Or better yet, a bullet of your own, but then you'll be vulnerable again as you reload, an agonising few seconds that will unfold only as you inch into your next position.

Why not throw the gun instead? Not bad. Maybe you were out of bullets anyway, or waiting on a reload from the last bit of business. Superhot's carnage doesn't just give you the time to overthink everything, it is also controlled by strict rules, and two of those rules are very helpful here. Anyone hit by a thrown item will instantly chuck their own weapon in the air for you to catch. And any weapon caught is instantly ready to be fired again.

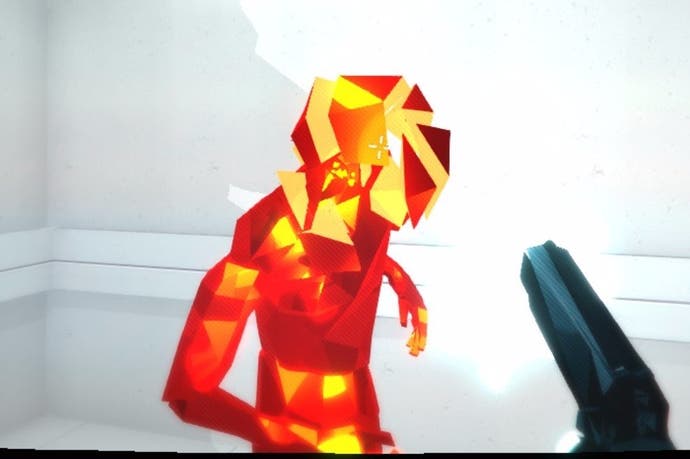

This kind of thinking continues to unfold in ten-second chunks across an inventive array of locations, most of them snug or warrenous or both, and with a suite of entirely coherent tweaks to keep things fresh. Shotguns or katanas replacing standard revolvers, say. A jump/slide move, and then locations to use it in. The whole thing is high intensity - for a short game, it's completely knackering to play - and the art direction opts for sheeny white-box settings and enemies made from sharp fragments of red glass. Reservoir Dogs by way of Gormley, with those basic artist mannequin shapes conveying a surprising amount of humanity. Strike them, and they clutch at their chests, heads bowed. Medieval supplication almost, presenting the skull for the coup de grace. Shoot them - in this fiercely standardised bloodshed, each bullet that hits is an insta-kill - and they fragment, crimson limbs coming apart to reveal golden interiors. Glass? More like glossy sweets. Rhubarb and custard. Hard-boiled candy.

It works for the course of a whole campaign as maps grow and shrink, safe in the knowledge that the basic three-way trade-off - you're juggling time and space as well as the quirks of each weapon - will keep things fresh no matter how many enemies warp in just when you think you've shattered the last one. It's cruel and it's beautiful with it. Time only moves when you do. Clockwork. Everything in the game plays along, right down to the reticule of your gun, which twists through each reload before locking into position once there's a round in chamber. Total information. Only a final mechanic, delivered in the last third of the game, threatens to shift things slightly too much into fantasy.

It's intoxicating. And at the center of that word: toxic. This is Superhot's most audacious trick, in fact. While the missions that unfold showcase the inescapable delight of make-believe violence more honestly than any other game I've ever played, the meta-narrative that strings them together - a thing of hackers, cracks, and terse chats played out on a humming, flickering computer terminal - urges you to consider why you love this horrible business quite so much in the first place. Why is it so pleasing to kick a man and then shoot him with his own gun? Why do you push the guy out of the window in the most lavish possible manner, just because the game tells you to "make him fly"? Why those scenes in which you're tasked with doing nothing - actually just stand still and don't move an inch - only to be told: good dog? Actually, maybe Superhot over-eggs it a little at times. It doesn't need its leitmotifs of CCTV cameras and prison cells to make it clear: this is an extravagant, exuberant, perceptive rumination on obedience and cruelty.

It's awful and undeniably fascinating to be confronted with your own craving for violence (there's an excellent joke towards the end about our need for some limp form of justification when it comes to powering our atrocities) and Superhot's success is so total that you may likely end up a little sick. Sick at the thought of the game's ingenious clockwork - and your own. There's a brilliant endless mode unlocked once the credits have rolled, and inventive challenges to work through after that. I can't face them right now, to be honest. But I'm afraid I'll be drawn back in eventually.

Nice choreography indeed. Superhot's too witty and thrilling to be a cold treatise on digital slaughter, and too disturbing and acute to be the mindless blaster that it is so good at subverting. Like Manhunt - another great game I never want to play again - this is that rare piece of charmingly curated violence that dares to provoke difficult thoughts. You may not like where it leads you, but that's the tricky thing about obedience, isn't it?