Why is video game lore so awful?

And finally, the truth behind the Jordache Dig Master.

There have been times during my career that I've found myself at a press event, listening to the creative director of a role-playing game, talking about their forthcoming release. Very, very often they will say something like, "there is such a rich story behind our game, there is a lot of lore for players to discover if they want to go deep". And, I have to admit, I inwardly groan.

Partially this is because I'm a terrible person. But also it's because video game lore can be... well, just awful.

The problem is, video game creators are prone to making two erroneous assumptions about what constitutes a deep narrative. The first is that volume equals depth. In the classic tradition of epic science fiction and fantasy literature, studios will craft thousands of pages of backstory, often involving many hundreds of characters and vast intergalactic wars. Sometimes it seems as though, early in a narrative meeting, one writer will say to another, "okay, let's set this in the middle of a war that has been running for a 100 years"; then their colleague replies, "No wait, how about... a thousand years?" And then everyone agrees this is exponentially deeper. It isn't, it's just an extra nought on the end of a conflict that, without context, pathos or human tragedy, is ultimately meaningless.

From this point, a lot of games indulge in a form of narrative carpet bombing in which story fragments are simply dropped onto the world from a great height in the hope that they make some sort of impact. Scrolls, emails, Post-It notes, letters - all crammed with text and left for the player to discover, "if they want to go deep into the lore". But so often this feels like stealth exposition, a way of filling in the backstory disguised as a reward for inquisitive players. The Witcher is a wonderful game series, but it does rather treat the Northern Kingdoms like a novelty bookshop, littering every shack, castle and cavern with pages of unexpurgated text. If I wanted to read the novels of Andrzej Sapkowski, I would jolly well buy them.

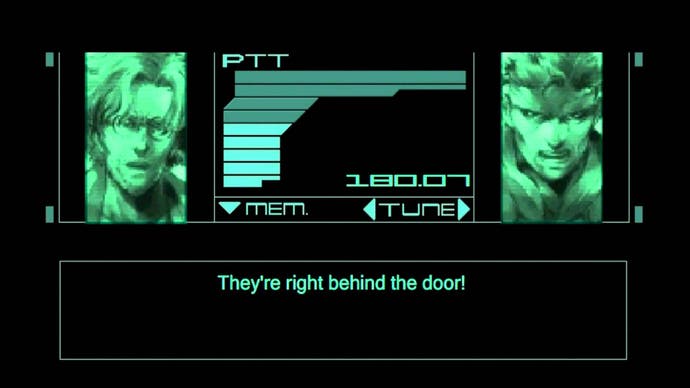

The other problem is the belief that obfuscation equals depth. In the Final Fantasy and Metal Gear Solid franchises for example, the timelines, relationships and plot structures are so tortuously complex, so shielded within arcane terminology, that it's almost impossible to engage on an emotional, empathic level. Yes, Kojima makes lots of super smart postmodern jokes and references throughout his games, but they are buried beneath narrative labyrinths that feel inaccessible, not because they're intellectually complex, but because they don't make a whole lot of sense. This doesn't feel like great story-telling.

I mean, I understand the theory behind lore placement. It's about allowing players to discover story content, rather than having it shoved at them; it's about pull rather than push, to use the horrible language of UX methodology. Bioshock is a wonderful example of this - obviously the audio tapes provide backstory in entertaining and intriguing chunks but then you also have the whole mise-en-scene of Rapture, the way certain scenes are carefully set up to tell the story of this failed utopia almost in tableaux form. The environment feels like a carefully curated museum of lore rather than the ramshackle narrative flea market that many subsequent games have become. I trusted the motives of the writers - and that's not always the case.

I actually think trust is a key issue here. The world of Elder Scrolls: Skyrim is effectively a giant instruction manual, a great warehouse of bloated backstory where you can't walk for more than five minutes without being hit about the head with a 100-page lore nugget. Journey, meanwhile, conjures a mysterious evocative world by providing the player with a few ruins and some ancient symbols. I cannot help but feel that the latter game trusts and respects its players while, the former wants to scoop story into their flapping mouths.

A better, more respectful use of lore can be found in games that reward inquisitive players with stuff that plays no real part in the overriding narrative. "A lot of people are really psyched to be valued in this way, including myself," says ex-journalist and now narrative designer, Cara Ellison. "For example: Love Fist in Vice City. Love Fist are a joke Scottish heavy metal band featured on the radio in that game, but I love them so much I look for signs of them in every single GTA title. In GTA 5, Willie from Love Fist turns up and that kind of thing is a joke that is 14 years old. That's a lot in game years."

Yes! What I love about this example is that it is a genuine reward rather than an exposition trap. The best games are the ones that use environmental storytelling to develop secondary narratives that can run alongside the main game rather than simply add detail to it. In Grand Theft Auto, for example, Rockstar North builds multiple mysteries and hidden sub-plots into its landscapes: The bigfoot myth, the alien space ship, the Mount Chiliad conspiracies - these all provide curious players with a totally parallel narrative universe that allows for interpretation and discussion. It is living lore. Portal is another wonderful example. The story of Rat Man and the whole 'cake is a lie' meme exist entirely separately from the logic puzzle framework of the main game - they don't explain it, but they do comment on it, they play with it, they indulge our curiosity rather than just shovelling information at us. For the Deus Ex series, Warren Spector and his team came up with a brilliant way of making the game's background lore work: they based it on real-life. I didn't mind digging into the mass of information provided in these games because I was learning about cool stuff like Mount Weather and Majestic 12. There is literally nothing I can do with my knowledge of the Lucky Old Lady statue in Skyrim's city of Bravil.

As far as I'm concerned, Hidetaka Miyazaki and Fumito Ueda are the masters of action adventure lore building. In both Shadow of the Colossus and Dark Souls, the approach is minimalist and ambient; there are no lengthy tomes on history or genealogy to discover, players must pick up on clues from architectural features, from the placement of items and enemies, from the tiniest scraps of information. In this way, the player is not a customer to be gamesplained at, but a narrative archeologist, chipping away at the world as though at a fascinating artefact from a lost civilisation.

I think one thing we have to remember is that, as a narrative form, video games are still ridiculously young. In the space of just 40 years, storytellers have had to cope with a medium that has gone from single screen-based 2D locations to vast open worlds. There are doubtless new conventions to be discovered. Perhaps the future is about emergent narratives where environmental relics - emails, letters, runes - change procedurally, reacting to player actions in the story, so no one gets the same bunch of lore. This will raise lots of questions about authorial intent and the shared nature of game narratives, but these are questions that seem fun.

Here is a final story about lore. Twenty years ago I had a job as a writer at a game development studio called Big Red Software. For three months I was tasked with writing the lore for a racing game (I'm not kidding - that was my actual job) called Big Red Racing. The team felt that we should perhaps explain why players were driving diggers and hatchback cars across the globe and also on the surface of the moon. I came up with a lot of text about an intergalactic racing league, and named all of the vehicles - I even featured reviews for them taken from fictitious specialist magazines like Mud Buggy Enthusiast and Truck Fancy. I named the digger after the character Beth Jordache from Brookside who stabbed her father and buried him under the patio. It was quality stuff. We didn't have environmental storytelling in racing games in the mid-nineties though so most of this went into the manual.

Then a couple of months before the game was released, Domark, our publisher, balked at the cost of printing such a vast instruction booklet for what was basically a dumb racing game and cut the lot. A whole summer's work, gone.

But they were right. It didn't really add anything, it was indulgent, and in the end players got to enjoy this game with all its incredible mysteries intact. I am certain that fans argued for years over the true meaning and origin of the Jordache Dig Master. No one will ever care that I spent several weeks writing that nonsense or that now it is gone forever. Lore is as expendable as memory, and even less reliable.