How Thimbleweed Park recreates the glory days of graphic adventure games

Monkey Island creators party like it's 1989.

Thimbleweed Park's pitch is simple: Monkey Island and Maniac Mansion creator Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick are making an oldschool point-and-click adventure that looks, sounds and plays like a Lucasarts title from the late 80s. You look at Thimbleweed Park once, think "yeah, I get what they're going for", and move on. But having played nearly a half hour of it at PAX East, it becomes apparent that by staying true to its quarter century old roots, Gilbert, Winnick, and co. have created something that feels genuinely fresh in today's landscape.

There's a few different ways Thimbleweed Park captures this lost art of the classic point-and-click adventure. My favourite is how it handles dialogue. Rather than have players scroll through a cyclical dialogue tree until they've heard all the witty banter, Thimbleweed Park stays true to the original Monkey Island where most conversations only let you pick one response before the natter flows forward in one direction. This means that players inherently miss a lion's share of the gags, but it certainly punches up the pacing.

When asked if it bothered him to spend so much time on jokes most players won't see, Gilbert tells me "No. Not at all. Because you can come back to it later, maybe on a second playthrough. In Monkey Island a lot of the dialogues people never went down and discovered and that's fine! I think it gives the game depth."

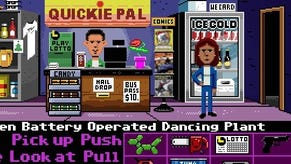

Another surprisingly delightful throwback is the comically dated UI where players interact with the scenery by selecting from a menu of verbs with their cursor. Lucasarts phased this out with titles like Full Throttle and Grim Fandango and the genre never looked back. Why would it? Why would you want to clutter roughly a quarter of the screen to issue different commands for "push", "pull", "open", "close" and more? Because it's fun, that's why. And why is it fun? Probably because the player has to be more considered in their actions rather than simply clicking on everything until something happens. Sure, you could exhaust every input option on every item, but that's a joyless activity for a reason.

Thankfully, Thimbleweed Park doesn't barricade every obvious interaction behind this intentionally cumbersome UI. Click on a closed door and the game is smart enough to know you want to open it. Click on a mirror and it'll know you want to look at it. Click on a person and it'll know you want to talk to them. Plus it provides a bevy of hidden jokes, particular when you try to "pick up" people. (An oldie, but a goodie.) This retro input system runs the risk of being tedious, but in practice it's exquisitely measured.

Gilbert defends this archaic mechanic saying that it's only frustrating when it's nonsensical. "As long as you're doing it in a clever way," he says of the verb select system. "You don't want to do it in a way that's just obscuring the solution to a puzzle. People shouldn't feel like they have to just randomly try all the verbs on all the objects. It should make sense."

Another controversial concession to the days of yore is that unlike Broken Age or Telltale titles, interactive hotspots aren't plainly marked. You need to actually hover your cursor over an item to see if it's interactive. "When you're highlighting all the touchable items I think you take away a lot of the mystery and exploration of those games," Gilbert says.

Of course, the downside to this was that a lot of old adventure game puzzles were needlessly difficult due to certain mandatory objects being itty bitty hidden puzzle pieces you need to painstakingly search for. But Gilbert is adamant that's not what they're doing here as each interactive item looks like it should be interactive. "Pixel-hunting is horrible and you should never do that," he states. "We don't do pixel-hunting."

Thimbleweed Park's minimalist approach also gives it a grander sense of scale than something like the visually splendid, but ultimately shallow Broken Age made by Gilbert's old comrade-in-arms Tim Schafer. That game's scope shifted drastically as its budget expanded then condensed, resulting in a polished title that ran out of steam far too early. Gilbert promises he won't make that mistake, which he hypothesises is due to its smaller budget and low-res style creating an easier road map to plan.

"We've really tried to keep the scope of the game in line. We did a lot of work in the beginning budgeting and scheduling and so we knew this is how much time we have," Gilbert says. "I think there's points where restraints can actually be a good thing. Having constraints on your budget or time can focus you down to the important things to do. Had we raised $3m we may have gone completely out of control."

A small budget doesn't necessarily mean Thimbleweed Park will be a small game. Gilbert says it will be "about the size of Monkey Island 2" with close to 100 different locales. Gilbert recently revisted the original Maniac Mansion and first two Monkey Island titles and found their slow and steady pacing to be on point. "The thing that really struck me with both of those games is how they opened up the world. You're kind of a little area of the world to explore, and then as you solve puzzles the world kind of opens up more and more and more. It's like on of the rewards of solving a puzzle is new art. So that was one thing we really wanted to do with Thimbleweed."

Beyond simply revitalising old lessons, Thimbleweed Park promises to tell its own original tale too. The demo I play focuses on a Mulder & Scully-like duo of special agents (cutely named Agent Rey and Agent Reyes) assigned to a murder case in the backwater Pacific Northwest town of Thimbleweed Park. Given that The X-Files and Twin Peaks are returning these days, Thimbleweed Park's detective spoof could not have come at a better time. "I like to think it's because we did our Kickstarter they decided 'oh, we should jump on the Thimbleweed Park bandwagon,'" Gilbert jokes.

The agents only play a small role in this demo, however. The bulk of this section focuses on an extended flashback about the town's prime suspect - a cursed insult comic named Ransome the Clown whose life has fallen to pieces after mercilessly taunting an old gypsy woman in his audience. Now he's cursed to never remove his "goddamn makeup". And his wife left him. As did his mistress. Plus his house burned down. Oh, and he's bankrupt. Ransome the Clown was never a nice guy to begin with, but it's impossible not to sympathise with his plight, giving a surprisingly effective human angle to this gag-a-minute parody.

Thimbleweed Park shows a lot of promise that's predicated on a lot more than mere nostalgia. It doesn't seem to invent anything new, but it salvages elements of game design that were perhaps buried prematurely. Based on its early demo, Thimbleweed Park is a retro throwback that lovingly preserves something we didn't know we missed.