Lumo review

Enchanted.

Lumo is steeped in the nerdish romance of the British 1980s video game development scene. For those who lived through those days, this wistful isometric puzzler, an ode to John Ritman's 1987 game Head Over Heels, is a reminder of mornings spent in the computer room at school, when kids competed for a seat at a BBC Micro.

Lumo calls to mind old exercise books, heavy with pencil-drawn maps of computer game layouts (indeed, the maps you unlock of each of its dungeon's floors are scribbled in just such a book). It's the kind of adventure that had to be snatched before dinner, when the only prayer on your lips was that the cassette would load the first time.

Lumo is the Finnish word for 'enchantment'. It's a reference to the protagonist, a dinky magician who totters about beneath the floppy brim of an oversized mage's hat. But it's also a reference to the spell under which any veteran of this forgotten genre will surely fall.

For the young, whose eyes are free of nostalgia's mist, the premise is straightforward and the execution no less beguiling. You must traverse a series of interlocking rooms, collecting keys and solving simple puzzles to gain access to previously inaccessible corridors. Each room appears as a discrete challenge, and is replaced by the next in sequence only when you touch the exit door.

It's a game free of text; you must survey each scene and figure out its silent demands. Part of Lumo's delight comes from the limitation of the interactions available to you. Initially, you can't even jump properly, only run about, uselessly. Soon you can leap, push, bounce and swim, but there's no generic attack or action button. Aside from the odd spider, which can be shooed away with the right kind of light, the obstacles here exist in the mind and, to an almost equal extent, in the fingers.

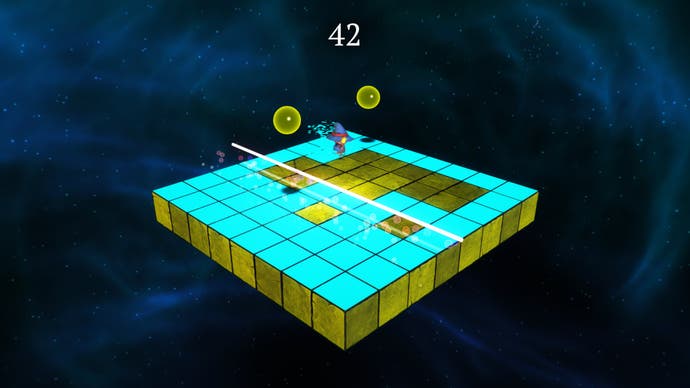

Lumo is a physically demanding game. Your character must negotiate narrow ledges and still narrower beams to reach the exit door of any given room. You must leap precariously between tiny stepping stones that skim the surface of toxic lakes. Much later in the game you gain a magical staff that is able to temporarily burn fuel to light up otherwise invisible pathways in the environment, some of which move in ghostly patrols.

You cannot rotate your view into Lumo's world, only slightly lean it to the left and the right. Accurate jumping in isometric space is a challenge many will never quite master over the course of the game. There is particular frustration when trying to jump onto dangling chains, the precise location of which are incredibly difficult to discern from an isometric viewpoint.

Nevertheless, the challenges are brief enough that, when you finally make the necessary jump to the exit door, your patience is amply restored. In one room you might need to duck through the gaps made by swinging lasers. In another you might need to shunt ice-blocks around without shattering them in order to create an impromptu staircase.

Even outside of the Time Trial mode, these puzzles have a Crystal Maze-like attraction and intensity. While the dungeon is labyrinthine, it's usually clear where you need to head next and what for. Visual clues indicate you need to locate, for example, a missing wheel from a minecart, or a missing gem to fill a statue's empty fist.

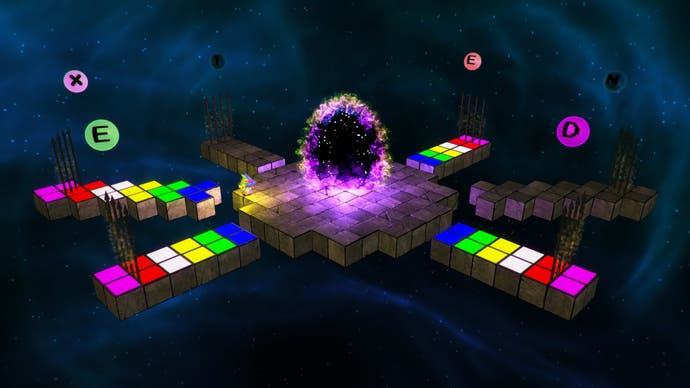

Lumo's knotted environments are also riddled with collectibles, which lure you further onward. There are rubber ducks, which are harvested by jumping on their heads, often requiring a hazardous bounce above a fatal pool of water. There are coins, cassette tapes, arcane letters and, at the core of your endeavour, four enchanted pieces of computer storage hardware to find. There's an emphasis on trying to bend the rules to find these bonuses too, with many items reached only when you manage to break from the confines of a room over the top of the brickwork, rather than through the door. The function of each of these collectibles isn't made clear for many hours; this is a substantial game, comprised of close to 500 rooms.

In contrast to, say, Jonathan Blow's pristine work, where every puzzle idea expands in elegant yet coldly technical increments, Lumo's ideas have a scrappy, soulful character. Sometimes ideas repeat without elaboration. More often they flare once, without repetition. Ideas you expect to be explored as the game progresses lead nowhere.

This is a game filled with special case animations and objects, as if designed by a kid whose head is filled with more ideas than he has space to set down. Indeed, designer Gareth Noyce, who previously worked on the Crackdown series, has spoken about how, as a ten-year-old, he would scribble ideas for new Head Over Heels rooms on paper. Noyce appears to have kept that sense of childlike eagerness into adulthood. It defines his latest game, which makes up for a lack of rigour with bountiful joy and generosity.

Perhaps Lumo's great asset, however, is its novelty as homage to a rare vintage. While the majority of the medium's early classics have been revisited, reignited and repackaged by contemporary designers, isometric puzzle games in the style of Knight Lore, Head Over Heels, Amaurote, Solstice and Equinox have been mostly overlooked. Noyce began this project wanting to answer the question: 'What would those games be like today?' Lumo is a fitting title for the answer he's found: enchanting.