The story behind War for the Overworld's messy development

This one's a keeper.

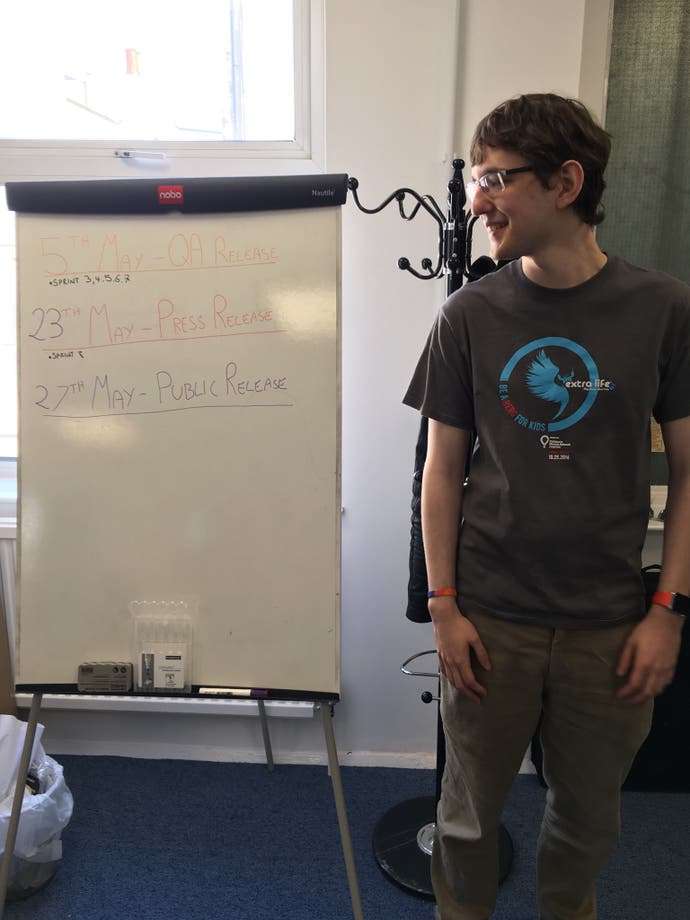

When I first met Josh Bishop back in November 2012, he was a wide-eyed 20-year-old computer science student from Brighton who had banded together with fellow Dungeon Keeper super fans to crowdfund a spiritual successor called War for the Overworld.

Now, three-and-a-half years later, I meet Josh again, this time in an office tucked away in the busy heart of Brighton town centre. He's not exactly battle-scarred by the journey that began with over £200,000 raised on Kickstarter, but in his eyes I detect a glint of newfound wisdom, in his voice the determination of someone who's been through the video game indie wringer - and survived to tell the tale.

Josh's story is not his own. He heads up a small group of developers called Brightrock Games. Its office, I'm surprised to discover, is the very same Eurogamer - and its parent company, Gamer Network - called home before we relocated to an office just down the road in spring 2011. I'm fascinated to see what Josh has done with the place.

We chat in the room I used to work in sat opposite Bertie (we affectionately called it the cupboard because it was, well, pretty cosy). Now, it's a space for meetings. There is a table and a couple of chairs.

"No-one had made games before," Josh says, thinking back to the Kickstarter launch. "Everyone was a fan of Dungeon Keeper, and we were on a Dungeon Keeper fansite, and we all wanted to make a new Dungeon Keeper game because there was no new Dungeon Keeper game."

War for the Overworld's Kickstarter pitch had a lot going for it. It traded on nostalgia for a much-loved 90s video game series that was ripe for a revisit. The video featured voice over from Richard Ridings, the original voice of Horny. And there was even an endorsement from Peter Molyneux himself. Molyneux, remember, had founded Bullfrog, the developer of Dungeon Keeper. Having him say a few kind words set the Kickstarter on the path to success. "That legitimised us quite a lot in a lot of people's eyes," Josh says.

War for the Overworld's pitch was simple: do what Dungeon Keeper rights-holder EA wouldn't. It was billed as the "next-generation" dungeon management game. You would play as a villainous god-like entity in charge of running your very own dungeon. Josh, at the time, pulled no punches: this would be the game for fans of Dungeon Keeper, he said. This would be what they had waited years for.

But for Josh and the developers, actually making good on that promise was anything but simple.

Looking back, Josh admits that he and the developers were naive. They vastly underestimated the amount of work - and money - that would be required to build the game they had pitched. And they went into that work without properly planning the project.

"We had two-and-a-half programmers," he remembers. "One of our programmers was half producer. I was the designer, but I was also running the whole company and also working with every single person on the team, and putting everything together. Our art team was three full-time people and a couple of part-time people. The team was tiny, for the scope of game. It was very naive of us to try to do something this big, but we just really wanted to do it."

It didn't help that the developers all worked remotely. Josh was based in Brighton, with others based in Germany, France and Australia. For such a young team with no real world experience of project management, this distributed structure was always going to affect productivity.

This naivety meant that, just over a year after the Kickstarter success, Josh and the other developers had to face up to the fact that War for the Overworld had got away from them, and that the money was running out. They decided the only option was to announce a delay of the game and launch on Steam Early Access. "That was useful from a money standpoint and a feedback standpoint," Josh says, matter of factly.

Most backers responded positively to the delay, announced in February 2014, and encouraged the development team to take its time to ensure War for the Overworld realised its potential. The game launched on Steam Early Access a few months later, and it had the desired effect: enough money came in to keep the lights on. Heads down, again, and more development.

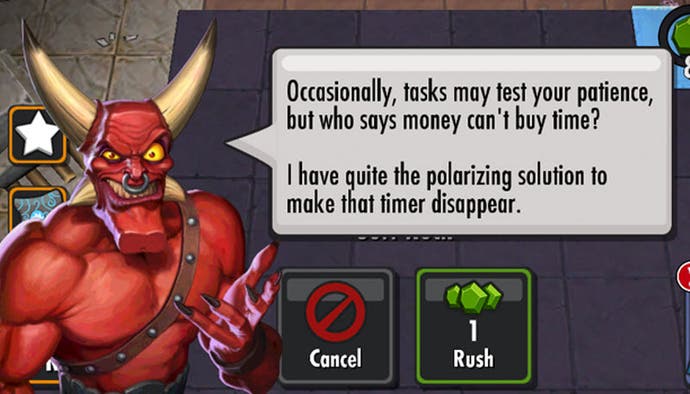

Amid the turmoil of development was the odd bright spot. In June 2013, popular YouTuber Total Biscuit praised War for the Overworld in an early look video. But the best was yet to come. In December 2013, EA did for War for the Overworld as big a favour as Josh could have hoped for: it released Dungeon Keeper for mobile.

This game re-imagined Bullfrog's classic as a free-to-play Clash of Clans clone, and it did not go down well with the series' army of fans. In Eurogamer's Dungeon Keeper mobile review, Dan Whitehead called EA's game a "shell of Bullfrog's pioneering strategy game, hollowed out and filled up with what is essentially a beat-for-beat clone of Clash of Clans".

While Dungeon Keeper mobile was a PR disaster for EA, it was a PR gift for War for the Overworld. The furore around the release sent angry Dungeon Keeper fans on the hunt for alternatives, and the light shone brightly on the in-development War for the Overworld.

Josh is diplomatic about Dungeon Keeper on mobile, but can't contain his glee when he remembers the signal boost it gave War for the Overworld. "Suffice it to say, the coverage of Dungeon Keeper mobile was helpful for us, from a sales standpoint," he said. "It was quite a significant bump, akin to a Steam sale."

War for the Overworld's link with EA took more surprising turns. In October 2014, I reported on the fact that EA had got in touch with rambunctious actor Richard Ridings about reprising his role as Horny, the devilish mentor of Dungeon Keeper, but his agent told them he couldn't accept the job because of a non-compete clause in his contract.

What non-compete clause? What contract? It had to do with War for the Overworld, which Ridings had worked on previously, the agent said.

Of course there was no non-compete clause in the contract, no stipulation that Ridings could not work on some other video game. And back then, EA's ill-fated bid to relaunch Dungeon Keeper on mobile devices hadn't even been announced. What foresight Josh would have had to display to have seen that one coming.

So, what was Risings' agent playing at? "I don't know," Josh told me back then. "He has a new agent now. We sorted that out. But it was a bit weird."

I also chuckled when I learnt that during the War for the Overworld Kickstarter, someone from EA got in touch with Josh to ask for an impromptu Skype call. It was a call Bishop had expected, at some point, but he was nervous all the same.

"I had heard on the grapevine that EA might be doing something Dungeon Keeper," he told me back in 2014, "after we'd started our Kickstarter." Bishop handed over his Skype details, and the mysterious EA person video called. "I was like, er... I didn't really know what to think."

The person on the other end of the video call was Paul Barnett, a designer who was then an executive at EA-owned studio Mythic. Barnett had played a key role in EA's now closed massively multiplayer online role-playing game Warhammer Online, but had since moved on to the unannounced Dungeon Keeper mobile game.

According to Josh, Barnett lifted an iPad up to the screen to reveal a new Dungeon Keeper game. "He wanted to make sure we were a team of people who were passionate about the game and that we weren't backed by some big, other publisher," Josh said.

"He also wanted to tell us what we should and shouldn't do as far as taking elements from Dungeon Keeper, which we were following already: don't use Horny, for example, because that was a character they had invented.

"That was all fine. He was very friendly. We continued to have chats after that. It was all surprisingly nice."

Despite the delay and the ongoing concern over how much money the developers had coming in, War for the Overworld had generated a decent amount of goodwill among a small buy loyal community of Early Access players. That goodwill, however, did not last long.

War for the Overworld launched proper on 2nd April 2015 in a bit of a state. Riddled by bugs, the game was attacked by players who accused the developers of rushing the release.

It turns out, the developers did rush the release of War for the Overworld. Josh says they were forced to in what he calls the darkest time the young team had experienced since deciding to make a go of the game. A year later, he tries to make sense of it all, tries to understand why it went down as it did.

Late 2014, money was tight. Very tight. Josh and his team saw that the situation was dire, looked at their options, and set a release date for six months out.

Back then, the company's costs were almost entirely tied to contractors. There was no office, and so no overheads. All money made by the game went on wages. But the money well was drying up.

"We asked most of the core team, how long can you go without being paid?" Josh says. "April was where we ended up."

Other factors were in play. War for the Overworld had secured a physical release with a small publisher called Sold Out. Sold Out had boxes in production, and they were being sent to shops. There was no turning back, now. The April release date had to be met, by hook or by crook.

"There were a lot of wheels in motion that meant we couldn't have delayed the release, even though we really wanted to, because it just wasn't in a state we were fully happy with," Josh says.

During the fortnight running up to launch, the developers worked "almost 24/7", Josh says. The team had all moved into a huge house in Hove ("It's a millionaire's mansion - the landlord eventually sold it for £1.4m - but the rent between eight people was quite cheap."). Eight people, all living under one roof, working day and night to get a video game ready to launch even though they knew it would never be properly ready.

The office, such as it was, was the bottom floor of the house. People would get up, shower, walk downstairs and work until they had to sleep. People would do energy drink runs at the local Tesco. Ready meals were pinged and dinged in the kitchen. The only non-sleep breaks were to watch the latest episode of Game of Thrones. An hour-long respite from, as Josh puts it, the "madhouse".

Whole levels were only being finished just weeks before the game was due to come out. War for the Overworld had the help of a fantastic volunteer quality assurance group from its community, but the developers simply didn't have enough time to get through all of the bug reports.

"It truly dawned upon us about a couple of weeks beforehand," Josh says. "We were like, okay, this isn't going to work. But we were so far gone, and we had our heads so deep in it, that we just kept going. And then release day came around and it was just like, oh, okay."

War for the Overworld came out and, as you'd expect, players weren't happy. Entire features had been rolled back. So broken was the game that the four-player multiplayer had to be disabled. The message was loud and clear: why on earth did you release it now?

"We don't have a chance to do that again," Josh laments. "That's the lasting impression of the game now."

War for the Overworld's Steam user rating - a controversial metric but incredibly important for such a small developer - took a nosedive, falling from 90 per cent positive before launch, to 73.

Total Biscuit, who had been War for the Overworld's most high-profile supporter, called it how it was.

"He was as nice as he could have been," Josh says. "He had been so supportive of us throughout development, that just hearing his disappointment was quite depressing. But yeah. It summed everything up. Everyone was just disappointed at what happened. It was crap, but it motivated us to get it fixed."

Josh and the others began working to fix War for the Overworld pretty much immediately after launch. From the ground floor of the house in Hove patches were pumped out, sometimes a few in a single day. The journey along the road to redemption was slow, but sure. The first major patch, 1.1, fixed most of the launch issues. Four-player multiplayer was, eventually, reinstated.

Then came patch 1.2, which saw the developers finish and redo a couple of the features they felt weren't good enough at launch. The game was rebalanced. "It was mainly trying to get multiplayer and skirmish into a state that wasn't broken completely from a balance standpoint," Josh says.

The developers spent five months in the house in Hove repairing the damage caused by War for the Overworld's troubled launch. It was an exhausting time, but a productive one. Then came a shock: their landlord announced he was selling up, and gave the team two months to get out. With War for the Overworld stabilised, it was a good time, Josh thought, to look for the company's first office.

It was also a good time, Josh thought, for a company refresh. So in September 2015 he formed Brightrock Games, with Subterranean Games, the name of the original developer, retained as publisher. It all started to look a bit professional.

The company signed the lease for the Brighton office over Christmas 2015, and moved in in January 2016. Brightrock managed to get a £35,000 government grant to help it set up shop ("a lot of paperwork, but it was worth it"), and then the landlord gave the team £15,000 to refurbish the place. It meant that the cost of moving from the house in Hove to an office in Brighton was paid for, apart from rent and taxes - another gift for such a small company.

The transition, clearly, has done wonders for the developers. No longer are they living under the same roof, but commuting to work. People arrive at the office, and leave. There is clear separation, some semblance of a work life balance.

Josh and the developers lived in the house in Hove for a total of six months. Despite the chaos, Josh looks back on the experience with some fondness. "I think without having that we would have been in much worse state than we were, because we were able to actually work together properly for the first time."

Brightrock is still unpacking when I visit a few weeks before the launch of War for the Overworld's hotly-anticipated DLC expansion Heart of Gold, which went live alongside patch 1.4 last month. There is much work left to be done, but Josh is buoyed by the progress made so far. The company has grown up, and War for the Overworld has repaired its reputation on Steam. At the time of publication, 85 per cent of recent Steam user reviews are positive.

War for the Overworld sold "okay" at launch, but with the release of each major patch came a small bump. "We've made more money than we've spent," Josh says. "That's a bonus and better than some people do." They've even managed to bring on some new people, including a new writer - "the first new member of the team for years", Josh smiles.

War for the Overworld hasn't made anyone a millionaire, of course. No-one owns a Ferrari (one person on the team has a working car). But Brightrock Games is debt free and looking to the future.

Two updates are planned. One is the addition of an advanced AI for skirmish mode. This is being built by one of the game's programmers, a German called Stefan Furcht who's halfway through his master thesis on video game AI. He's building War for the Overworld's AI as his final project. Two birds, one stone.

And then there's survival mode, which is a feature first mentioned back in 2012 as part of the Kickstarter. "Everything else has just happened before it," Josh says. "We are going to get to that."

Beyond that, Josh has designs for two more DLCs, which depend on how things go with War for the Overworld. "I very much want to do them," he says. And after that, a new game, which is already at the early planning stage. "We'll probably announce that next year, but we'll see how it goes."

Any regrets, I wonder?

"Not start the game for a month after the Kickstarter and plan everything properly," Josh says.

"Even if we had taken that month out of development, the amount of time and money and effort we would have saved by planning things properly and not having to redo a lot of work would have helped."

That's one regret. Here's another:

"Make fewer promises, both internally and externally. We had another leader on the team, early on in development. I originally didn't want to be the team leader, that just sort of happened. He made quite a few promises internally to the team, which ended up costing us quite a lot, and we had to backtrack on those promises.

"It had to do with the amount people would be paid and royalties, which we just simply couldn't afford. That was one of the reasons we had to go on Steam Early Access so early, because of how much this guy had promised people internally.

"He exited the team, and then I took over, and we had to cut everyone's pay to a more reasonable amount we could afford, enough for people to survive on until we had more money, which didn't happen until the game launched.

"When I started managing things, it was not a case of, oh, we can get rich, it was a case of, okay, we're going to run out of money. How do we survive?"

Right now, War for the Overworld and Brightrock Games are surviving. It's home to a couple of thousand players a week, Josh says, and has sold over 150,000 copies.

"We've done okay," Josh says in typically understated fashion.

"When I look back at everything that's happened, the amount of problems we've encountered, and the original guy we had leaving the team, all of the stuff we've worked through, we have done very well, given all of that. But I still don't like how the game launched."

Can Josh now, three-and-a-half years after War for the Overworld found success on Kickstarter, enjoy it? "Things are going a lot better than they were," he replies. "I enjoy most of it, yes. I'm going to enjoy it when the office is no longer a building site and we're fully out of the setup phase, which we've been in for three-and-a-half years.

"Ask me in two weeks, I'll say yes."