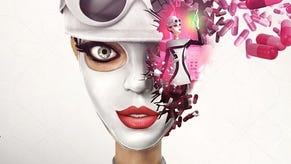

We Happy Few is a bit of a downer

Early impressions of Compulsion's dystopian yarn are cause for alarm.

Talk about a bait and switch: We Happy Few's prologue feels like it belongs to an entirely different game. The intro suggests a claustrophobic satire in the tradition of Portal and The Stanley Parable, casting the player as a rat caught in a violently jolly bureaucracy, somewhere in the heartlands of an alternate-history 1960s England. The Xbox Game Preview build opens, like the recent trailer, with player character Arthur Hastings busy at his desk, operating a censorship machine through a cheery haze of mood-altering drugs, till a chance article about his long-suppressed childhood dulls his buzz and slices away his allegiance to the regime.

The level unfolds like a quieter Half-Life chapter dressed up to resemble Stanley Kubrick's adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, with a clear main path but lots of ambient detailing to linger over. The stylings are vivid, the scripting brisk - a terrifying officer manager in clownpaint and a perky bowler hat, flip clocks and futurist ball chairs, psychedelic prints and appalling scenes in side-rooms, all of it funnelling you towards a grisly encounter with a pinata that doesn't, it turns out, contain sweets.

After 10 minutes of this, I was sold. Fair enough, the prospect of slipping through the clutches of an Orwellian state isn't that novel, but the writing and aesthetic have a distinct panache. A special nod goes to We Happy Few's lanky, sneering British bobbies - Slender Men turned pillars of the community whose helmet badges blaze like a Big Daddy's portholes. But then Arthur escapes the building after being outed as a dissident, and it transpires that We Happy Few is not, in fact, a taut dystopian labyrinth but an open world survival game with procedurally generated environments, plentiful resource bars, item crafting, day-night cycles, optional permadeath and spongy, Elder Scrolls-style combat.

It's a jarring shift and, with the strong caveat that 50 per cent of the world content and all playable character storylines have yet to be added, the execution feels muddled and unsatisfying. We Happy Few may prove a good game in the long run, given plenty of expansion and tweaking, but it's already not quite the game I was hoping for.

Your goal is simply to escape the town of Wellington Wells - a sort of DisneyLand Midwich, constructed in the aftermath of some act of collective villainy so dreadful that everybody is determined to forget all about it, hence a steady, government-enforced diet of "Joy" pills and a murderous reaction to anybody suspected of being a "Downer". The town is split into (at least) three regions, all separated by bridges and constructed around an underground safehouse, where you can sleep, lick your wounds and fiddle with your inventory in peace.

The rhythms of play are by and large familiar: seek out quest sites and resources while keeping one eye on your thirst, hunger and fatigue bars and taking care not to upset anybody you can't put down with a cricket bat. Disease is a factor, from rotten food that may give rise to dizzy spells or vomiting, to a plague that kills you slowly unless treated with special medicine. There's certainly plenty to ponder, especially once you fetch up against the limits of your Resident Evil-style grid inventory, but it all feels disappointingly rote after the wonderfully sinister intro. The combat in particular is a chore - stupefying trigger mashing plus spikes of irritation when the weapon you're holding shatters.

More promisingly, We Happy Few's druggy premise gives rise to a fairly deranged spin on stealth. It's not enough to crouch or make use of distraction items, such as cute wind-up rubber ducks that emit teargas, nor will you avoid scrutiny just by dressing appropriately for the area (posh suits generally spell trouble in the earlier, down-at-heel districts). You've also got to keep an eye on your high.

In the Village of Hamlyn - the heart of Wellington Wells, where the bunting is always crisp, the cobblestones fit to eat off and the water laced with uppers - townsfolk stroll about in a state of permanent euphoria. Anybody who seems less than blissful is treated with suspicion and eventually, run down like a dog. You can pop a Joy pill to blend in but this may, of course, interfere with your efforts to complete objectives. Take too much, and Arthur will lapse into a game-ending stupor.

Consuming Joy and other drugs affects perception - rainbows sprout from glassy blue skies, ghastly objects acquire a rosy hue and Arthur's wrists fly out gaily before him as you walk. There are also more specific mechanical repercussions, some of which feel quite arbitrary, such as the mansion gate that won't open unless you're thoroughly baked, and yes, you'll have to worry about withdrawal symptoms, though so far they're trivial - whirling crimson skies and a slight boost to hunger and thirst.

It's hardly a sophisticated take on drug abuse, and it's held back at present by the AI, which is prone to getting stuck on objects or taking umbrage with players for less than obvious reasons, only to forget about you once you quit the vicinity. Still, there's a hint of something engagingly warped here. Of note: Hamlyn's nosey old ladies, who are more alert than other "Wellies" to Downer behaviour but also more susceptible to the pacifying influence of a bouquet of exotic flowers.

We Happy Few's greatest annoyance right now is repetition. It won't take you long to notice recycled building types and layouts, and where other exercises in procedural generation like Nuclear Throne turn recycling into an asset, as players learn to survive and exploit particular setups, the twee architecture of Wellington Welles simply isn't much fun to revisit. The paths and secrets are obvious, the obstacles (such as tripwires) crude, and the sketchy AI makes infiltration a crapshoot.

As powerful as the game's portrayal of a rotten, saccharine Englishness can be, the art direction is also rather aimless in places - a jumble of ripped oil paintings, soiled mattresses and petal-filled bath tubs which feel like they've been hammered out, one by one, for visceral effect, rather than derived elegantly and as a whole from the narrative backdrop. You walk amongst them acutely conscious that they're props assembled for the purposes of a procedurally generated world, rather than items with a history and a place.

It's a sad contrast to Uncle Jack, the unseen regime's public face - a delightful study in dulcet chumminess who beams from every television set and chuckles from every loudspeaker, dispensing bedtime stories and tips about how to get rid of a pesky Downer. I'd happily spend a play session combing through his broadcasts, if it weren't for the continual pressure to eat, drink and sleep.

The addition of a proper narrative arc could address that loss of focus, restoring something of the sharpness you see in the first few minutes of the game, but I'm not sure it'll do much for the lacklustre survival elements and dull combat. We Happy Few has a ways to go, and offers up moments of fitful brilliance - certainly, it's nice to see some skewering of England's vaunted cultural heritage in the age of Brexit. But after a couple of days with the game, my high is already beginning to fade.