Blood in the gutter

What players bring to the games they play.

You might have heard of the Kuleshov Effect - the way that you can induce viewers to bring their own interpretation to two shots viewed together. Here's an example from a Hitchcock documentary: a shot of a woman with a baby, and then of Hitchcock smiling. Interpretation: he's a kindly old uncle. Here's another shot of a woman with a baby, and then Hitchcock smiling again. Interpretation: "He's a dirty old man!" Hitchcock says gleefully. It's the same shot of the same smile again. But we've seen something different in the gap between the two shots.

'Blood in the Gutter' is the title of the third chapter in Scott McCloud's The Invisible Art" his comic book about comic books. The 'gutter' is the space between comic panels - like the space between Kuleshov's shots. McCloud points out that an awful lot happens in that space - often as much as happens in the actual panels. But the artist doesn't have to draw it. They imply it, and then they leave it up to you to make it happen, behind your eyes rather than in front of them.

Games have more open spaces than either film or comics. Players come to things at their own pace and in their own order. Even in a linear theme-park-ride FPS, you're going to have a very different experience if you're running low on health or ammo. In more open, mechanics-driven games, scripted experience exists as chunks suspended in the larger game space, like floating islands on a prog rock album cover. The space between the islands is our equivalent of Scott McCloud's gutter. That space is where our imaginations can get to work.

So in Civilisation (IV, which is obviously the best one unless VI knocks it off that privileged perch), your Phalanx unit has survived for two hundred in-game years, gradually levelling up as it helps beat back attacks on its city, until finally it dies and the city falls. 'Fuck,' you say to yourself as you resist the temptation to reload. You say 'Fuck' mostly because the city's just fallen, but also, god damn it, that unit had fought hard and it deserved better.

Or in FTL, your whole crew dies except the Mantis you picked up six jumps back - but the Mantis crew-member keeps on flying. The whole Mantis race is only a set of sprites, a couple of stat bonuses, and two dozen widely scattered pieces of text storyline. FTL doesn't simulate any emotions or intentions for them. But there's that brave little insect avatar alone in the whispering pixelated nebula, and you can't but wonder what its motive is for carrying on. Is it memorialising your crew? Is it looking for a noble death? Does it just really like shooting the laser guns?

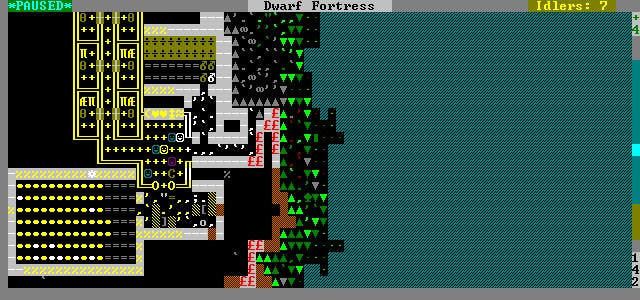

And then of course there's your Rimworlds and your Prison Architects and your Sims and your Dwarf Fortresses, where the whole point of the experience is to encourage you to care about the blobs of pixels and their relationship to other blobs, and which do so with enormous success. The gutters are awash with blood, here. In a good way.

This experience isn't the same as emergent gameplay, although emergence-friendly game design can help us have the experience. It's more like pareidolia - the human tendency to find patterns, to seize on two dots and a line and see a face, or to find a story in the turn of Tarot cards.

It isn't exactly a player-created story, either. A player-created story is made with a notebook and pencil, or a Unity license. When we bring our imagination to the gutters in a game, it's an ad-hoc collaboration between the designers and us. The designers of these games generally knew what they were doing. They put the gutters there for us to find treasures in.

It's as much like poetry as it is like anything. Poetry doesn't stop with the immediate meaning of its component words. Poems only work when you give a damn about them, when you engage creatively. The same is true of this kind of game design.

You'll notice I haven't talked about mods or fanfic or entertaining Let's Plays or Minecraft city-building or roleplaying in MMOs. Those are also, of course, exercises of imagination, collaborations between the designers and the players, and some of them are much more impressive. But right now, that imaginative spark is leaping behind the eyes of millions of players - players who'll never get around to building a mod and wouldn't be caught dead roleplaying online. When we engage imaginatively, even for a moment, we enrich our lives and all our future experiences.

I've said elsewhere that developers win by trusting their players to pay attention. This is an easier sell at the indie end than at the AAA end. In AAA development, the geological pressure of the commercial landscape often squeezes games into diamonds: compressed, lifeless, beautiful things, complete in themselves, where there's not much room for change and interpretation. But of course there are plenty of talented creators working in AAA too, and those commercial imperatives also recognise the power of engagement and customisation. Look at the team roster in any XCOM game, and you'll see what I mean.

And at the indie end, where necessity has always been the mother of invention, poetic design is a real opportunity. When your resources are limited, there's less temptation to fill all the gutters and illuminate all the shadows. Where there are gutters and gaps and shadows, there's the opportunity for player imagination. Minecraft wouldn't have got to where it is today if it had opted for total photorealism.

This is one of the reasons I'm suspicious of the idea of the holodeck, of immersive VR, of AI-driven simulation. People have been excited about this for decades. You pop on your helmet and there's a universe-sized MMO with an infinite content engine that builds all the plots for you seamlessly and fills in all the gutters. But apart from the moral and philosophical questions this raises, like 'wouldn't you need a wee every so often', man, what a shame to spoon-feed our imaginations. We'll probably all end up in VR brain hats anyway, once we've wrecked the earth and discovered fusion power. We needn't be in any hurry to get there.

Tolkien, who knew a thing or two about poetry, said:

"Part of the attraction of [the Lord of the Rings] is, I think, due to the glimpses of a large history in the background: an attraction like that of viewing far off an unvisited island, or seeing the towers of a distant city gleaming in a sunlit mist. To go there is to destroy the magic, unless new unattainable vistas are again revealed."

We all enjoy an unattainable vista or two. Let's not gentrify all the gutters.