The importance of games in difficult times

Alexis Kennedy on games, empathy and happiness.

I was halfway through a piece on poetic game mechanics as allegory, but then Trump won the US election, and I just didn't have the heart. So you're excused that until next month, at which point I'll probably do, like, a Christmas Pumpkin Spice column anyway.

This isn't going to be a column about how horrible Trump is, though. That's not new information to most people. Besides, I assume that statistically some readers would have voted Trump if they could (or did! hello in the US!). I'm not going to conceal my opinions, but I don't want to browbeat people on the other side of the political divide. In fact, that's sort of the point. I want to talk about empathy, and games, and happiness.

When you make games for a living, there are mornings when you wake up and something terrible has happened. That might be an election victory for someone who you think will do real harm. It might also be an earthquake or a tsunami or a picture of a dead child in the news. And sometimes, then, you look at the game you're making, and you think, bloody hell, isn't this all a bit frivolous? There's all this nasty in the world, and maybe I should be doing something more meaningful with my life.

So here's a couple of things that I focus on - things that I think make games worth the time and juice. Maybe I'm just making excuses to go on doing the thing I love, but you wouldn't be here if you didn't like games too.

Most of the good things that have changed in human society over the last hundred years have been because of empathy - the ability to imagine how someone else feels. Most of the bad things have been because of its lack. When you can put yourself in someone else's shoes, it's a lot harder to deny them freedom or the vote or the right to marriage or health care or a decent standard of living. When you understand instinctively that other people are individuals with feelings, not just sacks of noisy flesh, you're much less likely to lock them up or put bombs on their trains. Or leave passive-aggressive notes on the fridge.

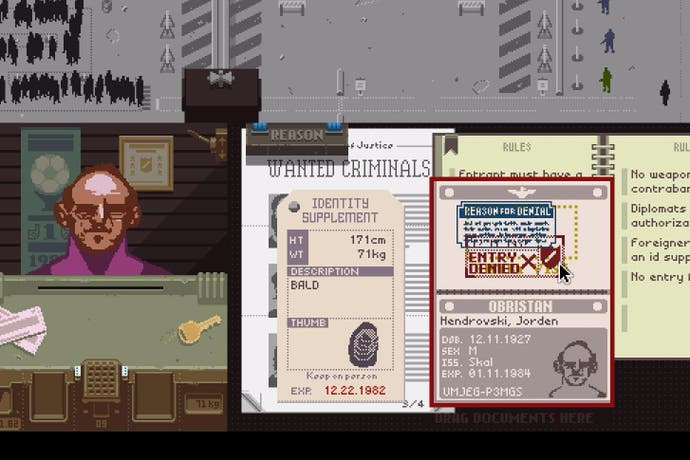

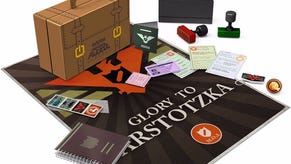

Games can help you imagine how it would be if you were someone else. I don't mean all games. Tetris is great, but it doesn't do anything for empathy. But I don't just mean worthy arty games either. Obviously something like Papers, Please is going to take your emotional imagination for a walk. But so is a decent CRPG where you spend a dozen hours being someone different. Or a 4X game where you make decisions you'd never make in real life. I think that even the experience of being an athletic moustachioed plumber gives us basic training in moving the focus of our interest outside our own heads. I think even a game as self-consciously sociopathic as GTA gives us a bit of practice in what it's like to be someone else.

Are games better at improving empathy than Proper Cultural Experiences, like literature, or serious art about the Holocaust? I haven't a clue. Games certainly aren't the only things that do this. Dickens moved the needle on the Victorian attitude to the poor of London, by writing novels and reportage that encouraged empathy. Right now, someone a bit racist somewhere is probably getting a tiny bit less racist because they're watching a film with a sympathetic protagonist from an ethnicity they don't usually like. All these things are good. Games just happen to be the thing I'm interested in.

But of course this isn't why we play games. This is the reason the serious games movement didn't take off the way that it was once expected to. You might remember there was a time back in the noughties when it was easy to find articles about how games were going to change the world. They were going to educate us as well as entertain us, they were going to raise social awareness, they were going to be persuasive in a way that other kinds of art never had been -

It didn't particularly happen. There are a lot of serious games, and there are even quite a lot of good, thought-provoking serious games that provoke useful insights about real issues. But it's hard for a game to compete on engagement when a designer's attention is diverted between crafting the experience and expressing an agenda. That was true when my generation were bought BBC microcomputers by optimistic parents so we could play educational games, and it's true now. It's not impossible for a serious game to be engaging, mind. It's just hard, because it's not why we choose to pick up a game.

We choose to pick up a game because the world isn't always interesting, and it isn't always fun. Sometimes it's downright gruesome. That's just how it is, and we have to live in it anyway, and games will only ever be a diversion... but diversions are also important. Essential, even.

And that's is the second thing that I focus on when I think about making games. If people are happier when they're playing games... that's a good thing. I don't mean games should be pure entertainment. (I've made a game about suicide and a game about cannibalism and I'm making a game about destructive obsession, so it'd be a bit stiff for me to say that.) I don't mean that it's more important to be happy than it is to be kind. I don't mean that we should spend our whole time on the sofa with a controller. None of that stuff.

But the world can be pretty grim, when you're broke or when you've just been dumped or when you hate your job or when your body's giving out on you or when a horrible orange man has just become the most powerful individual on the planet. If games can give us a holiday from the horrible, then they're worth making and they're worth playing. They're an absorbing thing to feed an hour or three into, and take your mind off your troubles. And sometimes, when you come out the other end, everything's a bit more manageable.

Make games, play games, learn to be kind, do what you can not to be sad. It's not exactly a political philosophy, but I wouldn't hate it on my gravestone.