How Amstrad Action changed my life

Ellie Gibson goes back to her roots.

During my 15 years as a video games journalist, I have repeatedly been accused of nicking my writing style straight from the pages of classic computing mags Zzap! and Crash. I wholeheartedly refute this spurious and frankly outrageous accusation. I've actually been ripping off Amstrad Action.

As everyone knows, the Amstrad CPC 464 was the true king of computers. The Spectrum and the Commodore were like Blur and Oasis - mainstream, safe, nominally diverse, but equally mediocre.

The 464 was cooler, smarter, less obvious; it was Pulp. Just as that band had a hip, subversive edge in the shape of frontman Jarvis Cocker, this computer had an integrated tape deck. (There was also the CPC 6128, which boasted a flashy floppy disk drive, but this unnecessary flourish rendered it a machine for pretentious wankers. It was basically Kula Shaker.)

I must have been about 12 when I got my 464, having lobbied my parents to buy a computer for months. I think the clincher was promising I'd use it to learn to code and secure a well-paid career as an ace programmer. (This did not work out as planned. I do have some BASIC knowledge, but opportunities rarely come up where the whole job is typing "10 PRINT "BUM" 20 GOTO 10".)

Because my family was desperately poor (we didn't get a dishwasher until 1991), we could only afford a second-hand computer from the pages of Loot. (For younger readers: this was like a sort of printed out version of eBay, except with less people trying to flog Kinects, and more serial killers.)

I scoured the newspaper until I found the perfect bundle: a 464 that came with a monitor, hundreds of games, and even a QuickShot II Turbo joystick. I knew from my research this was infinitely preferable to the original QuickShot II, the main difference being it had a red plastic base instead of a black one, which obviously made it more Turbo.

There was one problem. The machine was located in Tottenham. To collect it, my Dad would have to drive across London from our home in Lewisham, via the Blackwall tunnel. For non-Londoners, this is the equivalent of traversing a polar ice cap in flip flops, using badgers instead of Huskies.

But somehow I persuaded him. One bright, cold Saturday morning, we set out, having loaded up the Vauxhall Astra with pemmican and tennis racket shoes. The thrill of knowing that Amstrad CPC 464 would soon be mine warmed me from the inside as we explored the wilds of north London, watching out for crevasses and Suggs.

I was still brimming with excitement when we returned home seven weeks later (minus my younger brother, who we'd had to abandon in a snowdrift near Poplar.) While Dad plugged in the machine, I rifled through the huge plastic crate of tapes, wondering what to pick first - an old classic, such as Harrier Attack? Or something more mature and sophisticated, like Samantha Fox Strip Poker?

Eventually I settled on The Curse of Sherwood. I can't recall why. Maybe I was intrigued by how the familiar Robin Hood legend would play out when reimagined in digital form. More likely, I thought it looked cool because the cassette was white. I popped the tape in the deck, pressed play, and went downstairs to have my tea, happy in the knowledge the game would have loaded by the time I got home from school three days later.

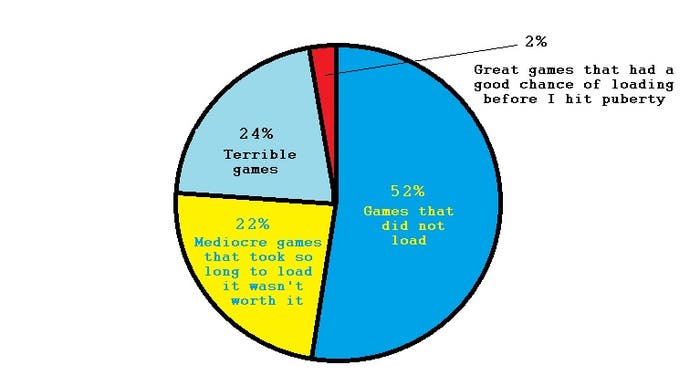

Over the next few weeks I ploughed through the cassettes in the crate, determined to try out every last one. By the end, the hundreds of tapes had been divided into four piles, roughly as follows:

Basically I was left with Treasure Island Dizzy and Xanagrams. I was going to need some new games.

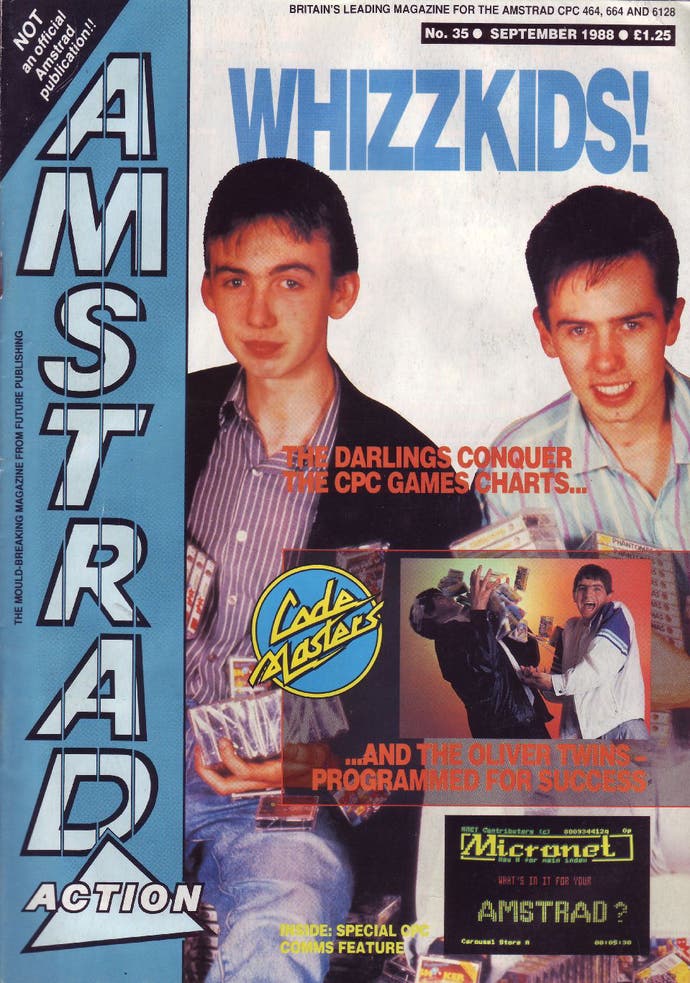

Knowing there were at least five years to go before the internet was invented, I turned to magazines. Specifically, Future Publishing's unofficial offering, Amstrad Action. I adored its knowledgeable yet jocular tone. I loved the way the writers' passion for the machine shone from each page, reflecting my own. Best of all, I liked the free demo tape.

It was truly a great magazine. The reviews were spot on, always careful to address the issues that really mattered to the forward-thinking 464 owner. Here's an excerpt from the review of Rick Dangerous 2, the highest-rated game ever to feature in AA:

"Each level has an entirely different set of graphics... As the laser beams thunder across the screen, the sound is echoed from side to side through the appropriate speaker!"

Now if that's not worth 97 per cent, I don't know what is. (Or what the developers would have to do to get 100 per cent - make the laser beams echo up and down, too?)

Other highlights included the regular adventure column by a guy called The Balrog, and the practical articles ("COLOUR PRINTING - How do you do it? What do you need? How good are the results?")

Then of course there were the BASIC programmes in the back. The idea was you copied these into the computer, letter for letter, and four hours later, assuming you hadn't made a single typo, you got to play a more simplistic version of Pong. What a time it was to be alive.

Back then, I had no clue where my love of gaming would take me. But it was Amstrad Action which first planted the idea that writing about games was something you could do for a living. Of course, it still seemed like a fantasy. Little did I know that years later, I would indeed get to spend my days sharing my thoughts on games, travelling the globe, and mainly slagging off Wii shovelware. I never dreamed that one day, I would appear in a successful video games TV show, and find myself watching Kriss Akabusi trying to play Track and Field by humping a giant space bar. (To be honest, I'm still not sure whether that one's actually a dream.)

So thank you, Amstrad Action, for changing my life. Thank you, Siralansugar, for inventing the best computer in the history of the mid to late 1980s. Most of all, thank you to my Dad, for driving all the way to Tottenham on that cold winter's day. Just think, if you hadn't done that, I might be a doctor.