The Sin City game that never was

Miller light.

It all began with a tease.

The year was 2007, and the Sin City franchise was riding high on the back of Robert Rodriguez's successful film adaptation. A small Australian games developer then known as IR Gurus and later rebranded Transmission Games - the name I'll be using throughout this article - decided it wanted in on the action, commissioning a 30-second concept video showing off what a Sin City video game might look like.

As a conceptual piece, the video struck all the right chords with Red Mile Entertainment, the US publisher in charge of the Sin City video game license. Eager to strike while Sin City was still hot in people's minds, Red Mile teamed up with Transmission for the biggest project in both companies' histories. It would end up being one of their last.

Inspired by prominent games of the time like God of War and Assassin's Creed, Transmission planned to tell a Sin City prequel story focusing on the aforementioned Marv. Using his trusty fists and props like bricks and chairs scattered throughout the environment, Marv would beat the snot out of his opponents in a manner not unlike the much-praised Batman: Arkham Asylum that would come years later. Hits could be chained into combos of increasing damage; enemies would attack from all directions but could be countered and stunned with an appropriately-timed button press; grabs and grapples would allow for environmental attacks like smashing an opponent against the wall or slamming them through a table.

Besides Marv, you would also play as two other characters: Miho, a Japanese hitwoman, and Dwight McCarthy, a reckless private investigator. Miho would sneak through the shadows and kill her enemies under the cover of night, climbing up walls and using the world around her to her advantage. Dwight, meanwhile, would scan the environment for clues and solve rudimentary puzzles, engaging in the occasional cover-based gunfight.

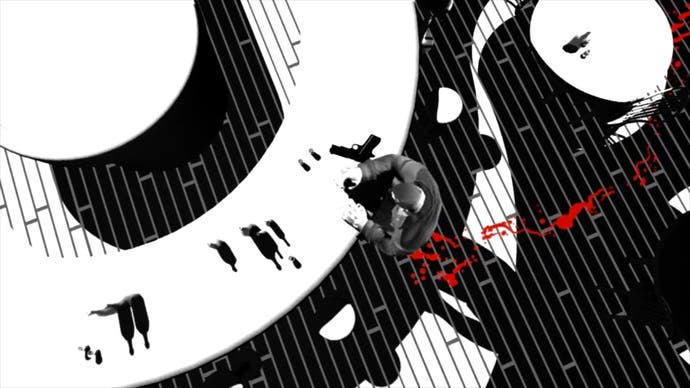

This video shows off a rough slice of the game Transmission put together before the project was cancelled. The first scene is the in-engine recreation of the original pitch video, while the second section shows off the various visual effects Transmission used to capture the Sin City aesthetic. While the project was still in its early days, you can already see the kind of game Sin City was shaping up to be.

Transmission's vision for Sin City was all about creating something unique, a game that combined the comic's signature art style and its deep, complex world with a then-unprecedented melee combat system augmented by stealth and investigation sections. It was ambitious, to be sure, but the team had it all planned out, and they were determined to prove that a small Australian studio could compete on the same level as the best in the world.

There was just one little problem, and his name was Flint Dille.

Based in the US, Dille was the man in charge of writing the game's story, approving Transmission's design decisions, and generally overseeing the project. Frank Miller, creator of Sin City, had hand-picked Dille to serve in his stead while he worked on his film The Spirit, but according to the team at Transmission, Dille was in way over his head.

"The thing to remember with Flint Dille's work," Simon Lissaman, concept artist on the Sin City project, tells me, "is that, having read his story beats and script stuff, it became immediately apparent he was not familiar with the books."

"The stuff we were getting back was really misogynist, and sexist, and left a very bad taste in our mouths," recalls a member of the Transmission team who preferred to remain anonymous - I'll refer to them as Anon from here on out. "The thing is, Sin City is a cut above that stuff. It's noir, that's the whole point, it's in that style but it's not revelling in sexist stereotypes."

Where Miller's Sin City uses sex and violence to establish its dark, grim tone, Dille's approach seemed intent on simply courting controversy. When he didn't like Transmission's choice of characters, the team was forced to replace Miho with Wendy, a latex-clad prostitute with exposed cleavage. Dwight, meanwhile, became Brother Mercy, an assassin priest more interested in slitting throats than investigating crime. Only Marv survived, and even he didn't make it through unscathed. Where he had previously been all about getting up close and personal with his fists, Dille decreed that Marv should spend more time shooting people with his gun Gladys, despite this completely contradicting Marv's story in the comics.

"Gladys has been sitting in a suitcase under [Marv's] bed for 20-something years," explains Lissaman. "Seeing him with a gun was actually quite unusual in the book."

Unfortunately, Red Mile supported Dille's direction, agreeing that the game wasn't 'sexy' enough and insisting upon the addition of a strip tease section where the player would engage in a Dance Dance Revolution style mini-game to encourage a stripper to take her clothes off.

"I remember when we heard about the stripper mini-game," says Anon. "[We] were sort of crying the whole time that it was even suggested."

The absurdity didn't stop there. How about a kick to the crotch that somehow sparks an entire plot thread about a cult of eunuchs? Or a church getting blown up right before it's supposed to appear intact in the comics? Or a casino built on the site of a Sikh Muslim burial ground, because apparently 'you know he's a bad guy because he's wearing a turban'. Dille and Red Mile were twisting Transmission's vision into something else entirely, something the team could no longer call their own. Tensions were rising, and the studio's modest foundations were starting to crack. Without someone to help shape all the conflicting ideas into a single, cohesive whole, the project was on the verge of buckling under its own weight.

Fate, however, had other plans.

In March 2008, approximately 12 months after the original pitch, Justin Halliday, producer on the Sin City project, flew over to America for a meeting with Flint Dille and Red Mile. After months spent butting heads, they were finally going to settle on a concrete vision for the project, a clear roadmap that would allow Transmission to focus on what it did best: actually make games.

That had been Halliday's hope, at least.

"We found that their vision for the game was very different to the one we'd been working on for a while," he explains. "They had this literal interpretation of the game where the game would follow the comic book panels. You would look at a comic book panel and you would play through that panel."

Effectively, Dille and Red Mile wanted a near 1:1 recreation of the comic. Locations, characters, story beats; it would all have to mirror the source material to a T. Transmission would have no creative license whatsoever.

Halliday came away from the meeting staggered, and from there things only got worse. Over Sin City's 12-month pre-production, the Australian dollar had risen from $0.90 USD to $1.10 USD, putting the kibosh on Australia's role as the industry's go-to for outsourced game development.

"Red Mile were under money pressure, and they kept asking us for new budgets on the game," recalls Halliday. Sadly, it was too little, too late. Just a couple of months after the portentous meeting, Red Mile pulled Transmission Games off the Sin City project, handing development to an unnamed studio. In July 2008, a Canadian company called SilverBirch acquired Red Mile, and less than 6 months later, SilverBirch shut down, taking Red Mile with it.

Back at Transmission, the loss of Sin City was met with a mix of disappointment and relief. While the project had started out as the studio's golden ticket, the vagaries of development had stripped away a lot of its lustre.

"At the end of the day, I felt like we dodged a bullet when that game got cancelled," says Anon. "I wouldn't have wanted to put my name to it."

"There was a bit of a sentiment when it got cancelled of 'well, that's not that shocking'," confirms Finn Morgan, one of Sin City's visual effects programmers. "It was surprising that some random studio from Melbourne got the IP in the first place."

Mired by conflict from within and without, perhaps the Sin City game that never was was simply never meant to be. Then again, perhaps we'll see a resurgence of interest in the franchise in ten years' time, with a studio like Telltale applying its trademark narrative formula and comic-book art style to Frank Miller's brutal universe. Either way, by all accounts, it's probably a good thing Sin City never saw the light of day.

"I think if that game had come out," concludes Anon, "people would have been disappointed. 'What do these guys think they're doing with Sin City, because that's not Sin City.' And we would have agreed with them."