The story of Crash magazine

It's all about the games.

If, like me, you were a ZX Spectrum fan growing up in the 80s, one of its trio of passionately assembled and dedicated magazines was an indispensable read. Like the famous platform rivalry of the time, each magazine had its fervent fans: Sinclair User was the longest serving, and had a drier tone; Your Sinclair (formerly Your Spectrum) gleefully brandished its off-the-wall humour in each issue, and is especially revered today. But for me, and many others, our magazine of choice was the appropriately-titled Crash, published by Ludlow-based Newsfield.

Most fans of Crash consider it ceasing with issue number 98 from April 1992 - just shy of 25 years ago. Published by Impact, a company created when Newsfield had been sold to Europress a year earlier, the magazine continued briefly, albeit as just a logo on the cover of one of its great rivals, Sinclair User.

"Whatever happened after issue 98 wasn't Crash, and we even put a poster in the final issue with a date range on it, like an obituary," recalls Nick Roberts, deputy editor of the final issue. "The Sinclair User 'incorporating Crash' thing, it was just the money men trying to claw back a couple of quid. Never sully the memory."

While there was a little more to it than Roberts reveals, it remains a sad end to an iconic publication of the 8-bit era. "Europress Group wanted an Atari ST magazine that was published by EMAP," says Newsfield co-founder, and Crash's first editor, Roger Kean. "And they came to an agreement simply to swap it for Crash. It was kept secret from us in Ludlow, so a big shock when the board announced it." For EMAP, it was the final revenge for a spiteful enmity that had spilled into the law courts. That's how it ended, though. Let's start with how it began.

In 1982, Roger Kean and his artist partner Oliver Frey were working at magazine and newspaper publisher Alan Purnell, gaining invaluable experience in the whole process of publishing, from journalism to CRTronic typesetting and rotary drum laser scanning. Oliver Frey's brother, Franco, working for an electronics development company, approached the pair with an idea for a new venture. "He had a German business contact who'd asked him to source computer games," explains Kean. "At the time, the high street was ignorant of computer games - if it wasn't Atari, it didn't hit the shelves." Franco Frey had discovered that dealing directly with the swiftly-growing number of software houses was the only consistent way of getting new games. The three men began sourcing titles and selling them via a posted magazine, complete with the unwieldy moniker of Crash Micro Games Action; then, a few weeks later, the home computer scene exploded. Newsfield, and Crash, were in the right place, at the right time.

"It was a colossal change," remembers Kean fondly. "The playground enthusiasm was just incredible, with the ZX Spectrum leading the way. Within days of our first mail order advertisements appearing in Computer & Video Games and the other popular magazines, one local lad, Matthew Uffindel, turned up asking if he could buy a game direct from us." The inevitable word of mouth created a snowball effect; within a week, the children of Ludlow were laying siege to Kean and the Freys, who realised, somewhat bemusedly, that they had something special on their hands; something that was about to change into an altogether different type of publication.

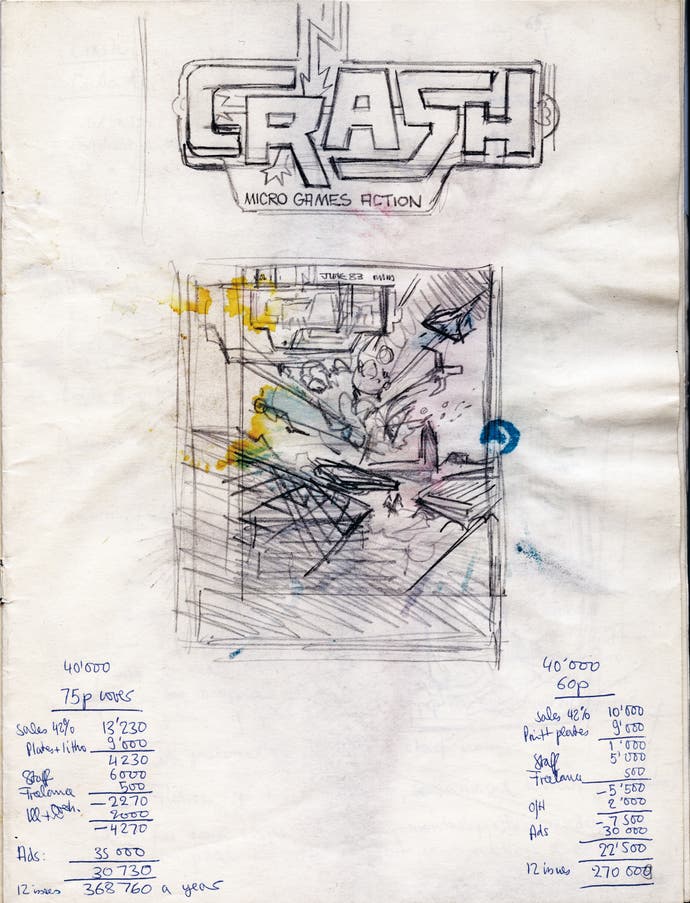

Crash's transformation into a monthly tome of invaluable Speccy-related knowledge came about late in 1983, with a portentous meeting between Kean and the managing director of magazine distributor Wells Gardner & Darton. "His son had shown him one of our mail order catalogues, replete with Oliver's line drawings," says Kean, "and he in turn had shown it to the WH Smith's news buyer. They agreed that the giant news retailer would be interested in stocking a real magazine along such lines, and it was up to us if we wanted to proceed." After a frantic period of costing exercises and work scheduling, the new magazine was confirmed, with that first inquisitive customer, Matthew Uffindel, on board as staff writer and reviewer, and the mysterious Lloyd Mangram in a similar role. The optimistic aim was to release the first issue in time for Christmas 1983. "The costing we made indicated we could only survive if the bulk of the magazine was printed on low-cost newsprint," explains Kean. "This meant restricting the amount of colour pages to 16 - essentially the pages reserved for advertisements and the four-page cover. However, the price point we wanted went out of the window as WH Smith said it was too low - so we had to bump it up, and then they said that for the new price we had to offer more colour as value...and on it went."

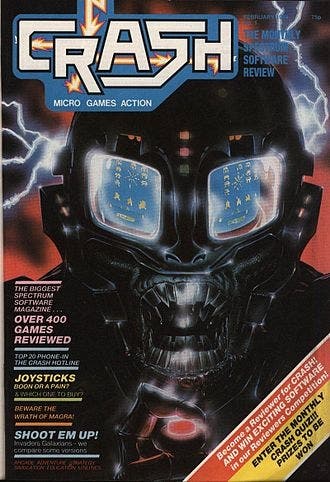

The continuing negotiations on the style and format of Crash pushed the first issue into the New Year. With over 75,000 words either written or edited by Roger Kean himself, the magazine hit the shelves in January 1984 and was an instant hit. The first of many fantastic covers by Oliver Frey disguised the sweat and tears that had gone into its creation. "Just about every word of that first issue - and a few thereafter - was written on an electric Smith Corona typewriter," says Kean. "The hundreds of typed pages were marked up to indicate typeface, weight, column width, font sizes and so on, and posted to a typesetting company in London, who then posted the galleys back for layout." Black and white photos and screenshots were dealt with separately, and sent to a local company for processing; colour transparencies were attached to the layout sheets with indicators of scale and sent to a London studio to process at the planning stage. Images were taken in a spare bedroom of Kean's home at 85 Old Street, converted into a photo dark room. In time, the team were even able to develop and enlarge images, including colour prints.

The biggest editorial change to Crash from its previous incarnation was its reviews. As had befitted what was essentially a sales catalogue, Crash Micro Games Action had never been anything but glowing in its opinion of the software it sold. "But Crash had to be critical," notes Kean, "and in spite of playing Combat, Asteroids and Space Invaders on my Atari VCS in the late 70s, I was not representative of the demographic." With Uffindel's help, Kean recruited a dozen regular kids aged between 12 and 18 who would turn up after school to discuss and review the latest games. "It was all very ad-hoc. Over the first few issues we weeded out those who were just doing it for the free games, rather than the desire to write something sensible. Later, we paid £5 per review, which was pretty good for the time, and of course that meant a flood of potential writers. We ended up with a pretty tight team."

One of this small cadre of young Spectrum fans, and budding writers, was 14 year-old Ben Stone. "My mum took me along to the interview," he laughs when I ask him what his parents thought of him working at Newsfield. "I think she was just pleased I was exercising my English skills!" Every Saturday, Stone and his fellow schoolchildren would descend upon Crash's new offices, situated above a branch of Victoria Wine. "There was a real vibe there on a Saturday. Roger would be there, Matthew too, and people like Robin Candy. It was really good fun, and we were mainly kids, so there was a lot of bad behaviour. I even remember seeing eggs thrown out of the window at someone!" Kean chuckles when I mention this to him. "A visitor seeing Crash Towers on a school weekday after 4pm, any weekend or during the school holidays would be forgiven for thinking they'd stumbled into a zoo. I'm afraid I didn't always help, instigating rubber band fights up and down the central staircase. But nevertheless a lot of work got done and, amazingly, hectic schedules were met."

Crash's youthful reviewers were given free rein to critique games as they saw fit. "At the start, I made it my job to check out how all the other magazines handled their reviews," says Kean, "and I wasn't impressed. But there we were, surrounded by local schoolchildren, the very market the software houses wanted to reach. It seemed obvious that they would be ideal reviewers, in that they would be candid about their opinions."

Stone, who impressed Kean in giving one of his first games a lowly 9 per cent score, recalls, "We were never pressured to give better scores. They were really solid about that, and it was probably the whole point of having kids involved."

Newsfield's support of its reviewing panel was tested in particular one month when Stone received an angry phone call from a disgruntled software house boss. "They had taken us out, schmoozed us, given us loads of hype about their games." he recalls. "And we breathed it in, wanting the games to be brilliant. Then, this one game missed out on a Crash smash [an honour given to the best games of any issue that scored 90% or more] and I got dumped on by this guy whose agenda was to get a Crash smash for all his games. I argued my case, but he said he was going to withdraw all advertising." With multiple ads across Newsfield's various magazines, the impact was considerable.

"I was in bits, and Roger said 'don't worry about it mate' and praised my ability to cope with the flak. But he was obviously pissed off, and I couldn't blame him!" However, despite its sometimes brutal opinion of the games it reviewed, Crash generally had a good relationship with most publishers. "Advertising departments always wanted to keep customers happy with great reviews," admits Kean, "but I always tried to wear my editor's hat rather than publisher's whenever a team came under pressure over a review."

By September 1984, Crash was selling well enough for a sister publication for the Spectrum's great rival, the Commodore 64, to be mooted. Newsfield's staff had already been slowly increasing, and now Kean needed a full-time assistant in order to take the strain off his own shoulders. The new employee, Graeme Kidd, was soon in charge of Crash, as Kean moved across to take over Zzap!64 when its original editor left. Kidd (who sadly died in May 2009) took over for issue 19 of Crash in the summer of 1985 - when the ZX Spectrum was almost at its peak - and he wasted little time in making his mark in controversial fashion, simultaneously pushing Crash even further up the magazine sales charts.

"During our first year, EMAP had taken swipes at Newsfield, calling us a bunch of 'rural pirates'," says Kean of the origins of the controversy. "The Crash team were also aggrieved that Sinclair User frequently claimed 'exclusive' previews and reviews, which was often not the case." Graeme Kidd, at the helm of his first issue of Crash, decided it was time to hit back. With the authorisation of Kean, issue 19 contained a hilarious spoof of Crash's rival, sporting a fake cover along with the 'Unclear User' sobriquet. It was an amusing, if unsubtle move, and one that EMAP failed to find funny, as the London-based publisher pursued an injunction to prevent the magazine being distributed, not on the suspected grounds of defamation, but for copyright infringement.

"It was just Graeme taking the piss really, but it backfired on us," says Stone. "Pretty much what we were saying was true, they were reviewing games that weren't finished and no doubt getting told not to worry as it'd be fixed in the finished game." Ultimately, EMAP won its injunction and the distributed issues of Crash 19 had to be recalled. "I remember lots of people chopping bits of magazines out before they could go on sale again," says Stone. But fortunately 60 per cent of the print run had already been sold - the costs were minimal, and six months later Newsfield and EMAP settled out of court. "In retrospect the sum we paid was worth it," beams Kean, "as the resulting wave of public outrage - giant London publisher slams rural underdog - pushed Crash from a median sale of around 50,000 copies a month to well over 100,000."

Other than its humour and review honesty, there was another reason for Crash's continual rise. From the very beginning, the magazine's covers had been designed and produced by Oliver Frey. With a background of working at the War Picture Library, Frey's work was not only artistically impressive, but frequently pushing the boundaries of what he could - and couldn't - get away with. "Oliver never shirked from painting something violent," remembers Kean, "often blood-streaked, and in a manner that could never be tolerated in today's safety-first culture." Controversial covers, such as issue 41's blood-soaked Barbarian and issue 31's depiction of a swimsuited Hannah Smith wrestling with an alien, often saw sales spikes, despite the protestations of WH Smith, John Menzies and indignant mothers.

Throughout the mid-80s, Crash remained a roaring success. But the pace of technology meant it couldn't last forever. By 1987, the Spectrum software market had begun to shift. Budget software and big licenses dominated, and the companies behind them changed as well. Stone, by now a full-time employee, recalls, "some of the guys we had got to meet, such as the Design Design lads, were so cool and awesome, and you learned a lot by talking to them - they were crafting games and having fun. Later, it was mainly people part of a large PR machine whose job it was to sell units. I remember the publishers behind the game Tarzan delivered this huge fruit basket to the office. They said 'it's PR, Ben,' and I said, 'just give me the game!' But that became the mainstay."

Most smaller software houses had either folded or been subsumed into larger publishers; the day of the bedroom coder was over. Roger Kean was busy elsewhere, running Newsfield, and on the cusp of releasing The Games Machine, a new multi-format magazine. The ZX Spectrum itself, having seen the rise of the Nintendo Entertainment System and Sega Master System consoles, was now fighting on another front in the form of the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST 16-bit home computers. When Kidd departed from Crash for The Games Machine, Kean returned home to his first editorship, and he was soon contacted by Nick Roberts, a 15-year-old Ludlow lad who had noticed that playing tips host Hannah Smith was departing the magazine.

"I remember I printed the letter out on thermal paper with an Alphacom 32 printer connected to my Spectrum!" laughs Roberts, who subsequently scored an interview with Kean. "If you can imagine, the office was something similar to Life On Mars - the radio was playing 80s music, editors chain-smoked at their desks and there was the smell of the chemicals used in film planning." Within two months Roberts was implanted as playing tips editor, and soon one of the most tumultuous periods of Crash's life began. "I didn't think the Spectrum scene was waning at all when I joined Crash," he points out, "and I don't think it did for a good two years after." Roberts's tips pages, in a pre-internet age, were a highly-valued part of the magazine. "Most of the content came from the sacks of mail we received each week," he explains. "There was loads of it: letters, maps and tapes of POKE routines. I sifted through it all to try and find things I thought the readers would find interesting." Roberts also sourced tips himself using a Romantic Robot Multiface. "I'd search for the code of the game to find POKEs that would give infinite lives or whatever and it was always a thrill to find messages in the code from programmers!"

Meanwhile, one of Crash's rivals, Your Sinclair, was beginning to regularly place game cassettes on its front cover, and the resulting increase in its sales was impossible to ignore. "It was the drop in the price of tape duplication that did it," laments Roberts. "We would end up each month spending more time trying to fill 15 minutes on a cassette than writing the magazine." As a result, Crash's page count drastically fell as it became all about the piece of plastic and magnetic tape on the front cover, a development Kean recalls witheringly. "The financial implications of sourcing games for the tapes, plus the huge cost of manufacturing and then sticking the damn things on something like 300,000 covers of Crash and Zzap!, had an effect on the extent of the magazines. We simply had to cut paginations to save on print cost. I hated what the covertapes did to Crash, and Oliver of course hated the ruination of his designs for covers which already had to cope with swathes of cover lines." It's a point I totally empathise with. As a reader, it was upsetting to see the glorious artwork of Crash reduced to a mere cassette-supporting role, much like the rest of the magazine, despite the allure of the bundled games.

The end for Newsfield came in September 1991, and by then Crash was contributing significantly less to its waning coffers. However, Kean, in union with Oli Frey and Jonathan Rignall, persuaded Europress Group to take over Newsfield's assets and set up Impact Magazines to publish some of its titles. Crash was one of these, and it continued until April 1992, and the infamous swap deal of EMAP's final revenge. But an ignominious termination aside, for eight years, Crash had had a glorious run, and positioned itself firmly in the hearts of countless Spectrum owners.

"Crash was conceived and written by people committed to reviewing as many games as were published each month," reminisces Kean, "and that in itself was a novel approach." Ben Stone, who had left the magazine two years earlier, recalls, "It was generally really good fun and we had a good laugh. Don't forget, we were essentially growing up together, and my career now, wouldn't have happened if I hadn't been a computer game journalist." Today, Roberts also remains in publishing, creating the monthly homage to games, movies and more, Geeky Monkey. "It was a dream job, and it was always fun. I learned magazine craft there from the best in the business: Roger Kean, Oliver Frey, Franco Frey and Graeme Kidd. We made it so readers would want to belong to the club, and they could, for just 90p a month!"

But what, I ask Kean, of Crash's longest serving member, the enigmatic Lloyd Mangram? "Um, he didn't exist," he says sheepishly, until I inform him that, like most readers, I was well aware of Crash's worst kept secret. "One thing I learned in London was that a magazine isn't credible unless it has a sizeable masthead. That first issue only had the three of us, so we needed to add more staff." Kean's solution was the nom de plume of Lloyd Mangram, named after Texan golfer Lloyd Mangrum. Rod Bellamy, a staff writer in the first three issues, was also fictitious. As Crash blossomed, real contributors replaced the fake ones, but Mangram remained as a stalwart of the magazine, right until its very end.

For Kean, like Roberts, working on Crash proved to be a platform to a publishing career that continues today. "The eight years of Crash proved to be a non-stop learning process," he admits, "something you tend to think you've already done enough of when you reach your mid-thirties. It was a learning curve in management too - by 1988 we had over 80 full time staff - and of course, creative writing and, above all, editing." Since Impact's demise, Kean has created several reference books and more at Thalamus Publishing. "It's also led to a maturing body of former readers demanding access at retro events and the like." he says, and reinforcing the decision to recruit schoolboy reviewers, Kean reveals a controversial parting shot. "I must dismay though, when asked what were my favourite games, I can only reply, that apart from Jet Set Willy, I rarely played any...and haven't since."

Personally, the reasons for Crash's success were clear. It read like a magazine that was written by kids that, like me, worshipped Sir Clive Sinclair's flawed little computer, and the wealth of imaginative and wonderful games that appeared on it. I would read it religiously every month, from cover to cover, and then back again. Its reviews could be trusted. Its art could be marvelled. Its insight could be believed.

It was our bible.

My thanks to Roger Kean, Ben Stone, Nick Roberts and all those whom I spoke to for this article.