Black the Fall review

Bloc and key.

An individual escapes his fate in an oppressive dystopia, moving across a landscape defined by monolithic yet crumbling industry: train yards, ironworks, storm drains and sinister research labs. The machine seems to produce nothing but grinds on, using people like meat. It's all stained concrete and rent steel, described in hard blue light, long shadows and little, glowing pinpoints of detail. Swathes of darkness and empty space dominate the small characters. There are many devious obstacles, but problem solving, subterfuge and ingenuity might just take our hero out of this nightmare.

I am describing Black the Fall, a new puzzle-platformer by the Romanian studio Sand Sailor, but I am also describing Inside, last year's insidious, brooding game in the same genre by Denmark's Playdead, creators of Limbo. This might not be the first time you've come across a comparison between the two, but it can scarcely be avoided. The design, mode, mood and art style of the two games are uncannily similar.

Sand Sailor told Polygon that the resemblance is down to a case of "artistic synchronicity", and certainly Black the Fall follows Inside's release too closely to be accused of ripping it off wholesale. (Though it's also true that a much earlier version of the game had a very similar look to Limbo; I think we can assume that Sand Sailor counts Playdead as a major inspiration.) Perhaps it's more interesting to look at where the games diverge, because Black the Fall is a subtly different beast - and not just in the matters of polish and production values, where it is clearly the work of a less experienced and well-funded studio.

Sand Sailor's developers are Romanian, and have both personal recollections and a shared folk memory of the country's grinding oppression under its Communist movement, which lasted from the end of the Second World War until 1989. Romanian Communism was hardline and nationalistic even by the standards of the post-Stalin Soviet bloc, and to make matters worse, from the mid-60s the Party and country fell under the control of the pitiless despot Nicolae Ceaucescu and his secret police. Romanians had it bad; there was no glasnost or perestroika there, no tearing down of walls, and Ceaucescu clung on so long and through such brutal measures that, in the end, his was the only Communist government that had to be violently overthrown.

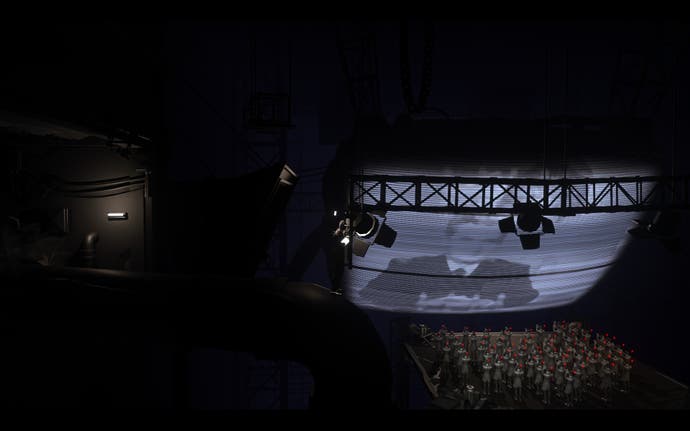

All this explains why Black the Fall is - or rather, starts out - so angry. It's a shock, because it's something we've become unused to. In pop culture, the Cold War is now usually explored as a time of intrigue and doomsday paranoia: a usefully moody, minor-key backdrop for spy stories. The era and its aftershocks feel sufficiently distant for Soviet iconography to have become kitsch, regularly used and abused out of context for its clean graphic power. But for Sand Sailor, and you suspect for many Romanians, this stuff is still real, and raw. In Black the Fall's exaggerated dystopia, you encounter images - like the giant screens showing the hectoring visage of the supreme leader, with his high collar and swept-back hair, or the mass of workers labouring in unison, heads bowed - that have become overused clichés, but which are allowed to reclaim some of their oppressive power here. If you didn't know the studio's background, it might seem a bit over the top, but even then the lack of pretension or artifice is obvious.

There's bitterness, too, and a little cruelty. In some earlier puzzles, your worker needs to use others to abet his escape, and he does so and leaves them behind without compunction. The main puzzle-solving tool in the game is a laser pointer, stolen from one of the game's pot-bellied, lamp-faced guards, that can be used to interact with machinery and also to select and command workers to do your bidding. These aren't the faceless, brainless golems of Inside, either; they're just people who've been conditioned to do as they're told. This story of escape starts, as I suppose many have to, with pure selfishness.

Things cheer up, relatively speaking, when you get outside - into a ruined and polluted wasteland, but hey, it's fresh air. Here you acquire a surprisingly chirpy companion, a robot dog, who can assist you in various ways, serving as a mobile platform or a distraction. Black the Fall's puzzles punish failure with swift death, in the Playdead style, and require some trial and error to solve. I wouldn't call them ingenious, but they have an implacable and occasionally pleasing logic that will see you through a diverting handful of hours of gameplay without much frustration.

The end of the game takes another, darker turn, before a last-gasp reversal that your character doesn't instigate so much as arrive at fortuitously. At this point, though, the requirements of a satisfying game narrative come a distant second to what the Sand Sailor team need to get off their chest. As the credits roll and photos of the actual 1989 Romanian Revolution scroll by, you think: that's on the nose, but fair enough.

The strange thing is that, as sincerely felt and personally motivated as Black the Fall is, the totalitarian nightmare it evokes isn't anything like as unnerving or threatening as the one Playdead created in Inside (from their relative paradise in liberal Denmark). Nor, when the tables finally turn and you get a chance to deliver a blow against the oppressors, can Black the Fall muster such a blood-pumping, visceral revenge as did Inside's startling closer. I don't think that's just down to Sand Sailor's lesser artistry. As surreal and creepy as Inside is, the fear it summons is an abstract and universal one - fear of the loss of self. It's something we can all feel and share. Black the Fall, though, isn't about your pain, it's about theirs. It's not here to look into your soul, it's here to bear witness.