The Shrouded Isle review

Blood will out.

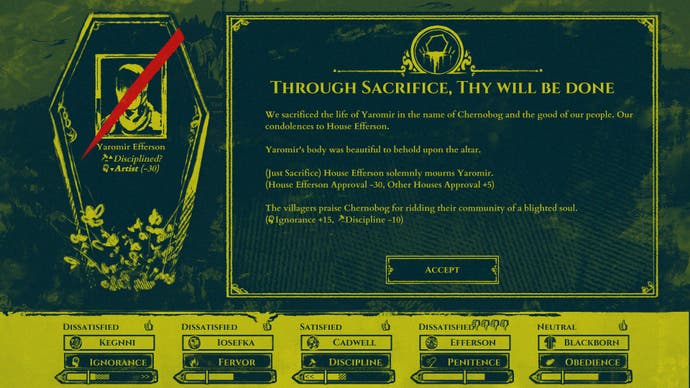

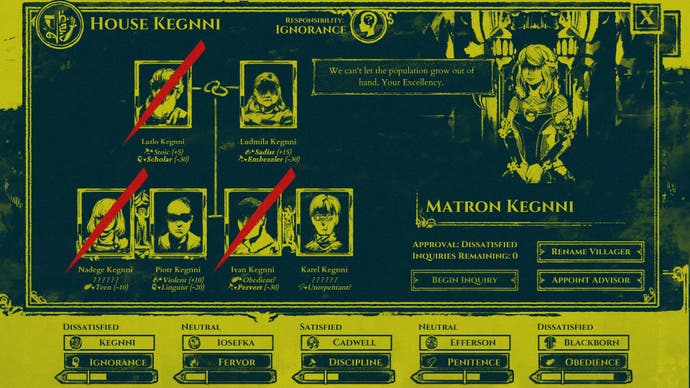

I can't decide whether to murder Yaromir Efferson. On the surface he's a model zealot, never sparing the lash in pursuit of sin, but I look at how repulsively literate our village has become under his eye, and I worry that beneath that righteous facade lurks the mind of a Scholar. Were this any other season he'd make a perfect sacrifice, but I butchered a member of the Efferson clan in the spring and they're threatening revolt if I do it again too soon. Ludmila Kegnni would be a solid alternative - she's been stealing from the altar fund, a capital offence, but on the other hand her Sadistic tendencies are an inspiration to us all. Who else, then? Ah yes, young Marya Cadwell. Of course, you could argue that being a Teenager isn't all that grave a sin, but fewer adolescents on our streets equals a more biddable populace. Besides, the Cadwells are pretty well-disposed toward me right now. Let's see how deep their loyalty goes.

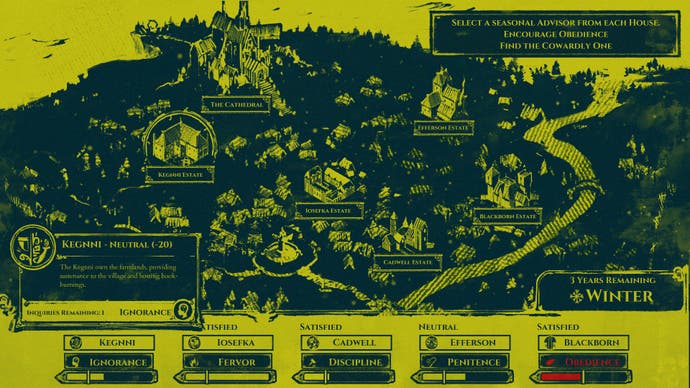

These are the kinds of ghastly decisions you'll make in The Shrouded Isle, a well-wrought Lovecraftian management sim distinguished by some beautifully emaciated monochrome art, which puts you in charge of a village cult just three years (twelve turns, or around an hour of play) from the apocalypse. Your mission, should you be morbid enough to accept it, is to grease the wheels of annihilation by sacrificing townsfolk to Chernobog, an undersea deity named for the God of the Night in Slavic myth.

Every season, you'll pick five advisors from the game's five clans - each a procedurally generated morass of virtues and vices drawn from a list of around 60 traits. Then you'll put up to three of these advisers to work, month to month, in order to raise (or, if you choose badly, lower) your community's levels of Ignorance, Fervor, Discipline, Penitence and Obedience. Neglect any facet of the community's spiritual life for too long and it's game over. Come season's end, you'll select an advisor to offer up to the god beneath the waves, permanently reducing the village headcount and in all probability, rousing the wrath of their kin. Allow a clan to feel Rebellious for more than a turn, and they'll take up arms against you. Think of it as a bit like carefully chiselling away the cliff you're standing on, stone by stone, root by root, till the ocean itself sees fit to sweep you away.

The first big wrinkle is that vices and virtues are largely a mystery to begin with. You can approach clan elders for hints before appointing advisers, and commission an inquiry to reveal a single trait if you have enough favour with that clan, but much of the time, you'll have to glean what makes them tick by watching them at work. This obviously creates potential for nasty surprises, like recruiting an Ascetic to boost local Discipline only to find that he's a closet Kleptomaniac. Unmasking major vices is, however, a blessing in disguise, because the juicier the sin, the more enthusiastically villagers (including the victim's relatives) will respond when you put that character under the knife. Where a game like XCOM is about making the best of what the RNG doles out, The Shrouded Isle thus sees you actively grooming reprobrates to serve alongside more dependable advisers, so you've got plenty of bones to throw Chernobog down the line. The god itself will occasionally complicate matters by whispering to you in your dreams, calling on you to hunt down one particular sinner while keeping a certain village stat extra-high.

As meshes of competing variables go it's hardly as ornate or volatile as XCOM, but for a piffling £7 or $10 there are plenty of grotesque involutions to unearth on replay. You'll learn, for example, that it isn't wise to reveal too much about a character you hope to sacrifice, because if that character turns out to have a major virtue your followers will be divided over the choice, losing as much of one devotional quality as they gain of another. Better to hide that light under a bushel, before snuffing it out. It's delightfully awful. Occasional semi-random narrative events add a bit of scripted malevolence or absurdity - you might offer to erect a monument to carrots to appease quarrelling farmers, or burn a passage of scripture which suggests that Armageddon is a few thousand years off rather than three.

Redolent of both Game Boy dungeon crawlers and Mike Mignola's Hellboy comics, the visuals are mesmerising throughout. The game's puritanical tyranny finds its echo in the palette, a glaring quagmire of yellow and black (alternate colour schemes include "sacramental wine" and "poison ivy"). Characters appear as ruined canvas portraits, their eyes seared away by shadow. The audio is marvellous, too: each clan has its own introductory orchestral sting, a skitter of pipes and strings that suggests a shaft of sunlight exposing something horrid on a table in a darkened room. The Shrouded Isle is essentially a few dozen pieces of 2D art with overlaid animations, but it conjures up an atmosphere of entrenched, ineradicable evil the average triple-A horror game seldom manages.

It's hard, nonetheless, not to wish for a little more meat on the bones after a few sessions. While suspenseful in its early stages, The Shrouded Isle tends to grow a little dry by year three, once you've discovered most of the vices and virtues in circulation - it feels like there should be another, over-arching campaign dynamic to shake players up towards the finale. Still, this is a marvelous blend of fanaticism and Machiavellian calculation, and a pleasantly wicked way to round out the summer lull.