How Tomb Raider got lost in the wilds

Lara Craft.

Have you heard of the North Pond Hermit? It's a wonderful story: strange and wistful. For 27 years a man named Chrisopher Knight lived in the wilderness of Maine, sleeping in a camp beautifully hidden amongst boulders and sneaking out, every few weeks, to steal supplies from the surrounding homes. People suspected he was there. It must have been a little bit like being haunted by a lonely ghost. Houses were broken into, candy, books, the odd Game Boy was lifted. Some people would leave supplies out for him, in a bag hooked over the handle of the back door.

And then one day in 2013 he was caught, and when he was questioned regarding how long he had been at it, his response was to ask how long ago the Chernobyl disaster had happened. He had taken to the woods just after Chernobyl.

Man, I would love to play a game about the North Pond Hermit: a game that captures the sad majesty of New England woods, with their cruel winters and bursts of autumn colour. A game that allowed you to learn a complex terrain, to make it your own, and yet to always feel that your existence, the life you had chosen for yourself out there, surrounded by people but not living amongst them, was tenuous and worth preserving. I doubt I will ever play something exactly like this, but the North Pond Hermit is often at the back of my mind as I plod through survival games like The Long Dark, and now, blasting through Rise of the Tomb Raider, he is frequently at the forefront of my mind too.

In a way, he is the reason this series has finally clicked for me. I have always loved Tomb Raider, and since Crystal Dynamics took over the series with Legend, I had continued to feel that one of gaming's greats is in safe hands. Legend is a wonderful game, as are Anniversary and Underworld. These are games that manage to capture the lonely wonder of the Core titles, while knowing which edges to smooth out a little. They are the Core games the way you remember them being, in a way: the frustrations and occasional clumsiness have been removed, leaving only the elegance and the sense of awe as you explore levels that feel intricate and coherent, as if you are wandering around inside an ancient machine.

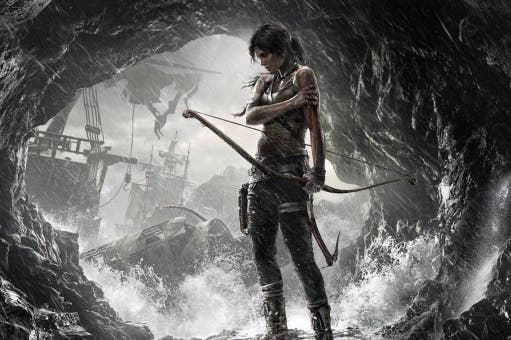

The reboot has been much harder for me to get my head around. I went to see Crystal Dynamics when it was in development, for a magazine piece, and I was struck at first by the sheer beauty of what the team was doing. That first demo, with Lara hanging from the rafters of some cultist's cave, engaging with a little light physics puzzling, and then racing to safety as the roof collapsed and the wolves attacked? It felt too vivid to be real. The rocks glistened with rain water while soot and sparks leapt from Lara's torch. And Lara did improbably cool stuff, too. Not the big stuff, the little stuff: she would reach out to steady herself on a wall. When she was inching through a narrow waterway, she would put a hand against the roof to maintain a sense of contact with dry land.

There was no doubting the care and skill that was going into this, but there were other things at work that didn't always feel very Tomb Raider. Lara Croft is a strange beast: she is posh and remote and unflappable, and yet through the allure of that control system - the sideways jumps, the backflips, the mantling that sees her doing a headstand if you press the buttons right, one leg dropping down before the other - there is an intense feeling of connection between player and character. The grid system from the Core games made this stuff explicit: once you understand the limits of her movements within this rigid environment, you could do pretty much whatever you wanted to.

That sense of connection was preserved for the Legends-era games, but all of a sudden in the reboot, a little distance had crept in. Lara would contextually do other things for you: she would crouch automatically when moving through low chambers, she would snap into cover to do all that glorious cosmetic reaching and steadying. A tiny thing, surely, but the athletics got a bit safer: like Nathan Drake there was a sense she could be drawn more obviously towards ledges on jumps that otherwise wouldn't quite make it. The plot, meanwhile, mistook grimness for character development. Players like me were off on an adventure. And here was all this suffering, all this falling on spikes and getting the wind knocked out of you. As the camera moved inwards and Lara took up more of the screen, there was a strange feeling that player and character were slowly separating at the same time.

I finally finished the Tomb Raider reboot a few days back. I enjoyed it, I think, although it took me over a year to complete, playing on and off, uninstalling and reinstalling. Because of this, and because of how devastatingly pretty it is, regardless of the harshness of the world that it's portraying, it retained a sense of spectacle to me: it felt like a tech demo right to the end. Sure, it settled into a groove, but I never lost my admiration for the way the camera bobs and rucks behind Lara as she clambers over this and that. And while Lara's rebirth is more of a shooter than I had expected, I still liked a lot of the shooting: the shotgun has a nice flat punch to it, the assault rifle barks and snaps. And that bow: the long pull-back, the target moving in and out of sight, and then the release and the perfect headshot.

My sense throughout was that Tomb Raider was changing, but it was hard to see what it was changing into. At times, there was a genuine attempt to marry the old Tomb Raider and the reboot. Moments when Lara first flings herself across a chasm, the world switches to slow-motion, and her ice axe hits climbable rock at the last second: a classic hero moment, maybe a defining moment? In that instance you could see how this Lara could become that other Lara. Equally, while exploring a stretch of coastline towards the end of the game, ancient rocks gave way to rounded concrete: a World War 2 gun emplacement, forgotten after the battle for the Pacific. The mixture of two things, both old and mysterious, rubbing up against each other, felt very Tomb Raider. And for a brief moment I was not surrounded by identikit enemies moving into cover: I was grappling and mantling and leaping from one spar to the next. Behind the rusting door of an old shack, I even found one of the game's optional tombs. This is surely a sign of the utilitarian muddle Crystal Dynamics found themselves in: a strong vision for a new character-driven take on Tomb Raider, but if you're not down with that, you can have a little of the old Tomb Raider a la carte.

The reboot remains a muddle to me over all: a beautiful, carefully made game that wants to be bold, but also wants to please everyone, and is not quite a total success on any front as a result. Last week I went into Rise of the Tomb Raider expecting much the same stuff, and the sequel does, in truth, hold close to the basic template. But there is a little shifting underfoot. At times, I see glimpses here of a future in which the new Lara Croft feels coherent and exhilarating.

Tellingly, most of these moments come in the first half of the game. Rise of the Tomb Raider loses a lot of its appeal from the moment, about a third of the way through, in which you get your first assault rifle. Suddenly, firefights, including a huge pitched battle as you move towards the final act, are suddenly viable. It's no coincidence, surely, that at the same time as I got that gun I started to notice how many enemies had the same face, and how eagerly they spilled from doorways and exchanged the same kind of combat chatter with their cloned colleagues.

But before all that - and in fleeting moments afterwards - the game genuinely seems to be settling into a groove. And it's a groove that the North Pond Hermit might recognise. Early on, I'm dropped into a wintry wonderland, an old Soviet base high up in the snowy mountains. All around are windblown shacks and craggy rock faces that I have just unlocked skills to be able to climb. This landscape is not a linear path: it is a complex arena, with many routes across it, many of which I can create myself, rope-arrowing new ziplines into being and breaking down doors.

Crucially, I am pretty much alone. A few wolves patrol the lower reaches, but my objective is not to seek out anybody and kill them, it's instead to knock out five radio transmitters, scattered about the place. For a happy thirty minutes, I do just that. I scamper around, navigate dead ends, work out where I'm headed - or where I think I'm headed - and rely on happy accidents to do the rest.

And all the while I am picking over the landscape, breaking off branches and pinching birds nests for the stuff I need to make arrows, picking mushrooms for poison ammo, collecting bits and pieces for bandages, and finding salvage, a kind of hobo currency that is far more fun to gather than it is to use. In truth, all of this stuff is far more fun to gather. The upgrades in Rise of the Tomb Raider are not particularly enthralling, and the character progression is largely unmemorable. But it's nice stuff as texture: a way of being in nature, in the world itself, is reinforced by scavenging as you move, picking up audio logs I will never listen to, filling out a map I will never look at. It's all part of the North Pond Hermit lifestyle.

And all of this became explicit as I started to realise that what I had thought was one of the reboot's more throwaway ideas might actually be one of its best. I'm talking about Base Camps, these little rest areas scattered around the map that allow you to pause, upgrade weapons and spend skill points, and fast travel across the game's landscape. (They also allow you to recap the plot if you haven't been paying attention.)

They're not save points, exactly, but they're a clever spin on it. In the new Tomb Raiders, you pretty much auto-save after every individual bit of business. There's no need for the Base Camps as way of taking care of progress. But they feel like one of the other uses of old save points: a moment to break off and reflect on the journey so far.

In this way, they remind me very strongly of something I had completely forgotten doing in the very old Tomb Raider games. In Tomb Raider 2, say, which I think had a quick save system, I would be stuck in the middle of a gigantic level, and worried that if I broke off now I would never pick up the threads again and find my way back to the adventure. As a result, as I moved through the game, I would pick spots in the distance - anywhere with a good vantage point, or that offered a decent sense of forward momentum - and I would save at that spot, turning it into my own little base camp before logging off. This sense of mild role-playing makes me feel a bit silly now, but it also bridges a gap for me, between the old Tomb Raiders and the new ones, the former seemingly slick but actually ornery, rather wonderfully harsh and prickly games in places, the latter coated in a patina of suffering, but actually a little too slick, and a little too accommodating at times.

Where from here? There's a new Tomb Raider in development, and it will be fascinating to see how it finds balance amongst all the forces now at play in Lara Croft's world: how the survival elements fit together with the cover-based shooting (with a bow, Tomb Raider makes for a surprisingly entertaining stealth experience; as with Crysis, I find myself hoping they leave the guns at home this time), and how the old Tomb Raider virtues of melancholic loneliness and complex, level-sized puzzles find space for themselves in amongst all the chatter of ceaseless enemies and an endlessly nagging UI. I have hope, anyway. And I can't wait to sit down at the first base camp in the new game and think about what's to come.