Splatfest is a reminder of Nintendo's greatest secret ingredient

How did you fight in the toilet roll wars?

It is so rare in games to go to war for something you believe in. And yet going to war is such a big part of the deal with games. You go to war against demonic entities in Doom. You go to war against space fundamentalists in Halo. Games are filled with rogue states and splinter groups, with orcs and Chaos creatures: all kinds of things that need a generalised shoeing. But these things are so numbingly removed from real life, so good-versus-evil that it's hard to feel like you have much skin in the game.

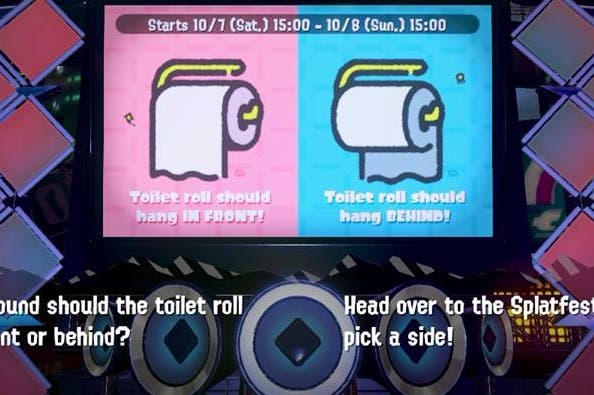

In Splatoon this weekend, though, I went to war for something I really cared about. Splatfest has returned, the weekend-long celebrations of ink-flinging that hinge on a 'what's better?' question. What's better: Ketchup or Mayo? Choose your answer and then prove it on the battlefield. What's a better super power, invisibility or flight? Pick a side and then get at it. This time around it was the age-old conundrum of how you should hang toilet roll. I took up arms as a front-roller. I fought back-rollers. I also often fought other front-rollers because there simply weren't enough back-rollers to go around. It was great.

It was great because Splatoon is great, of course. But there was an extra thrill this weekend, because I cared. I discovered that I have actual opinions about how to hang toilet roll, just as I have actual opinions of whether I prefer ketchup (of course I do) to mayo (I love Simon Mayo). With such a simple gimmick, something that barely counts as a game mechanic, Nintendo lead me back to a battlefield I have stayed away from for the past few weeks because of other more pressing concerns. Mainly laundry.

Nintendo keeps doing this stuff, and yet I'd never really noticed it before. I think of Nintendo and I think of colourful fantasy: the Mushroom Kingdom, the punkish squid of Splatoon. But that's because I'm not thinking very hard - I'm not looking at the fantasy to see what it's composed of. And maybe, I'm starting to realise, this is one of Nintendo's most powerful secret weapons: Nintendo's not afraid to invoke the real world, the world you already know very intimately, to make its games a bit more engaging. Magical settings, sure, but why not chuck in the odd landmark you already know to help orient you?

Take Splatoon. On the surface this is such a strange game, isn't it? Teenage squid fighting each other for territory. And yet if you pull it apart, there's so much that you already know about, so much that you can already relate to, that there's little need for a serious cognitive leap to get involved in the action. These squid are basically playing paintball. Their weapons are super-soakers and paint rollers and umbrellas. Their loot and equipment comes in the form of T-shirts and hats and shoes. The hub is a city square with cafes and sliding doors and a food truck. You are launched into each session by watching the kind of TV show that might pop up on The Box. These teenage squid, right, are basically teenagers.

And it's not just Splatoon. Mario's worlds are not really as fantastical as they might initially seem. Or rather the fantasy is composed of things that are very familiar: cup-cakes, ice cream, bean bags. The Mushroom Kingdom is a fantasy, but it's a fantasy that's often made of brioche.

Elsewhere, the WarioWare games that seemed like such a breath of fresh air in the early 2000s earned much of that freshness because they were simply about parts of the world that games had never turned to before. While other games were fixating on nazis and super soldiers and spaceships and aliens and medieval warfare, Wario was finding the fun in toilets, in cookery, in picking your nose. There's a game in the first WarioWare about catching toast. You don't need to wait to be told how it works, because it's about catching toast. (It didn't start with Wario either. Nintendo once made an arcade game about the high-octane thrill-ride that is vacuuming.)

It's so weird, isn't it? Or at least it is to me. Games hinge so much on the fantastical that it's easy to forget that they can sometimes make the fantastical humdrum. To paraphrase Hugo Dyson, when banging on about Tolkien (I initially thought it was C.S. Lewis speaking): Not another f***ing elf. And when games do turn to the real world, it's the extreme bits: the world wars, the knights and the castles.

And so Splatfest continues to be such a landmark date in my calendar: a date where I am asked to pick a side in a conflict I genuinely care about, and ponder a part of the world that I actually recognise. All while being a teenage squid with horn-rims and high-tops. Not bad, really. Not bad.