Reaching out towards the past in Assassins Creed Origins

Wings over Giza.

Editor's note: Once a month we invite the wonderful Gareth Damian Martin, editor of Heterotopias, to show us what proper writing about games looks like before we shoo him away for making the rest of us look bad. If you want to read more in-depth critical writing, you can find the third issue of Heterotopias here.

When we talk about history we are, more often than not, talking about architecture. From the cities in which we live and work, to those we travel to as a form of escape, we constantly encounter history through its architectural presence. The ruins or restored structures of cathedrals, castles, temples, tombs-they are preserved as interfaces with history, ways of accessing the inaccessible and long distant past. Even meagre structures, such as the steel teeth and concrete bunkers of the Normandy beaches, take on an incredible architectural power and worth through their proximity to culturally significant events. As individuals we constantly seek these places out, and stare from crowded streets at their unrelenting stones in hope of some form of contact. We might even touch them, idly running our hands, as thousands upon thousands have, along their walls. For many of us, these encounters will be the most powerful architectural memories we form in our lives.

When discussing Assassin's Creed Origins and its architecture, you'll have to forgive me for going back to the series' own origins. From the very beginning, architecture has been a central part of Assassin's Creed. When the first game launched, a decade ago this month, it integrated architecture into its gameplay in a way that had few precedents. There had been no Mirror's Edge, no Infamous, with Ubisoft's own Prince of Persia: Sands of Time being the most obvious precedent for freedom of movement. Assassin's Creed looked and moved like nothing before it, its open cities crafted around one central idea - the game's impressive climbing system.

Through this system, in which protagonist Altaïr's moves were realistically mapped to each handhold and ledge, the game's Holy Land cities became playgrounds where each brick, support, window or beam played a vital role. Though since that first iteration the series has smoothed out, simplified and sped up the climbing, making it increasingly easy to clamber across ancient rooftops, there is still something attractive about the clumsiness and difficulty of this first attempt. It asked focus and attention from the player, with paths up the side of structures often being indirect and complex, while badly timed traversal in the city would often leave you hanging from a beam in full sight of your pursuing enemies.

The necessity of keeping your attention on the next handhold or gap in order to wrangle this climbing system into behaving forced the player's attention onto the rough stone and bricks of Acre, Damascus, and Jerusalem. Each of these cities, modelled with a level of detail and care that few games of 2007 could compete with, became the centrepieces of the game. There was something in the act of touching, scrambling across and eventually surmounting these structures that felt like such a powerful way of connecting with historical architecture. I can't even guess the amount of hours I spent back then, moving from rooftop, to dome, to spire, seeing the city again and again from a thousand angles. At the time it seemed obvious to me that my experience of the game was an extension of my interest in and experience with real life historical architecture. Being given the freedom to hang from every ledge, cross every façade and take in the view from each rooftop felt like an impossible gift. For me the guards, the narrative, even Altaïr himself became distractions to circumnavigate in my wanderings of these spaces.

What struck me at the time was that if the historical buildings I had seen in cities around Europe functioned as a kind of interface for imaginary and real encounters with the past, whether that was gazing up at Notre Dame's gargoyles in Paris or exploring Namur's Medieval citadel in Belgium, then Assassin's Creed was the ultimate realisation of this interface - a chance to virtually map, explore and gain an unprecedented view of these structures. While as a real life visitor to one of these locations you might imagine yourself exploring the upper reaches, bridges and balconies of these spaces, in Assassins Creed you could simply go ahead and do it, letting your interest take you from architectural detail to detail. Even the architects of these buildings couldn't have imagined such a total experience of their designs would ever be possible. That such an incredible feat was possible felt powerful enough that I barely registered the game structures it was in service to. The original Assassin's Creed was a surprisingly sparse game, dotted with short missions, and with much of its space left tantalisingly unused. Its huge connecting "Kingdom" hub was so empty of content that many players simply rode straight through it, ignoring the stunning landscapes and hidden views that lay so pleasantly un-incentivised for anyone willing to wander.

A decade later and these supposed "mistakes" have been comprehensively corrected. Assassin's Creed: Origins, a soft reboot of a series that has more than 18 games to its name, feels almost sickeningly full. Everything from the overstuffed HUD and the glut of interlocking menus to the almost illegible map of mission markers, question marks and resource pockets, this is a game designed to fill every bit of Ptolemaic Egypt with things to do. It might be something of an obvious point, seeing as the series has grown a reputation for sensory overload by now, but when brought alongside its kin of a decade past it seems suddenly strange.

How did we end up wandering out of an empty kingdom to here? We're left drowning in numbers, from those that that chart experience, resources and attack power, to those that jump even more enthusiastically than the generous gouts of blood from bodies of photofit guards we don't know why we are murdering. Shrouded in all this, I find it hard to touch on that power I once felt - the beautiful strangeness of a game so besotted with history that it offered up its structures for you to explore in any way you might imagine.

And yet it is still there, that ability to touch every surface of the structures of the past through a virtual hand. Assassin's Creed Origins is, beneath those numbers, built on an exquisitely detailed, architecturally obsessed world. Though its attempts to portray its hero Bayek as combination of both a glib young man and a vengeful and mentally scarred killer is as incongruous as it sounds, this narrative flatness is layered on top of a richness and depth of detail that deserves better. Behind the humdrum of combat and hunting lies the most detailed simulation of Ptolemaic Egypt ever created, in science or art, or all of archaeology. Its focus may not be accuracy, but the comprehensive breadth of the sense of time and place it evokes cannot be ignored. And, desiring to be free of the tedium of its missions, I found myself turning the games HUD off and wandering its world as if I was playing the originals empty kingdom once again. It was then that I realised the connection, the true meaning of the word "origins" clamped so awkwardly onto the game's title.

There is a shared connection in the game spaces of the first game and of Origins that lies outside the series - the work of the painter David Roberts. A Scottish artist working at the end of the 19th Century, Roberts is often described as part of British Orientalism, a movement In painting that is often questioned for its romanticisation and Western colonial outlook of the so-called "Near East". But Roberts, unlike many of his peers was famed for his studies of architecture in the West long before he travelled to the Holy Land and Egypt. He was known for his accuracy, his sense of architectural scale, and unlike many other orientalists, he made many journeys through the places he depicted, often painting his images on location. Because of this his body of work shows an unprecedented view of the architecture and landscape of the Middle East and beyond. Long-time Assassin's Creed art director Raphael Lacoste has never hidden the huge influence of Roberts' iconic studies of the Holy Land on the first game, and with Origins turning to Egypt the series could once again return to the work of this master painter.

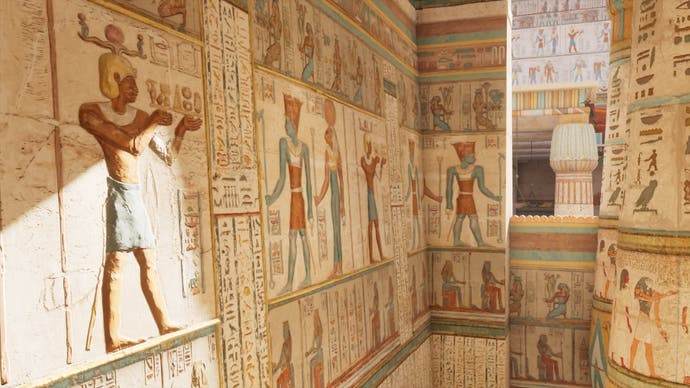

That's what I found, in my HUDless wanderings - images and architecture that like the first game's empty Kingdom evoked Roberts work beautifully. Just compare this study Roberts did of an ancient Egyptian portico to the shot of an Origins temple on this page. The colour, the sense of light and scale, it's all there. And the more I wandered in Origins, the more I saw of the same powerful sense of space and time that I had observed a decade before in the original game. Origins is a development too, of those beautiful cities of the early games, which while rich in detail were failed by their dull and awkward citizens. Assassin's Creed Origins feels alive in comparison, its layers of wildlife and work, of industry and daily life filling its world with variety and complexity. Finally the series' exceptional architecture feels matched by the life around it. And yet, for my first hour with Origins I felt frustrated by the way this was obscured, ignored and sidelined by the games structure. Even with the HUD off, playing Bayek seemed to anchor me to the series' failings. But then I discovered Senu.

Senu is perhaps the most important introduction to the series in all this time. An eagle that the player can switch to controlling at any time, her debut appearance feels like a disappointingly predictable way to retcon a contemporary military drone into a historical setting. Used for marking targets and objectives, at first she might appear to be just another overblown idea with little sense. But with the HUD turned off Senu becomes beautifully useless. With no targets to mark and no strange high tech overlay, flying as Senu pulls away from the violence, the tepid story and the endless numbers once and for all. There are no enemies, no barriers, and incredibly, no limit to the distance she can fly from Bayek. The first time I discovered this I went on an hour long weaving flight from Alexandria to Giza, observing this world with fresh eyes once more.

From this elevated perspective the rhythms of the games systems take on a new light. You can watch as the snaking forms of crocodiles stalk unaware fishermen, swoop among songbirds perched at the top of high domes, and track riders through the city as they follow some urgent path. The world feels empty, so to speak. Not empty of life, of activity, or of detail - but empty of the structures that dictate meaning. From this high up, above the chatter and the routine, you are free to imagine a story for every detail, a life for every citizen, a meaning for this world.

And in that form, Assassin's Creed Origins approaches another architectural image of history, that of the diorama. I began by talking about how it is the old architecture of cities that shapes our view of history, but there is another influence too. While walking through a cathedral or palace, letting our hands drift along old stone, might evoke a connection with the long dead people who did the same, there is something to be said for the elevated perspective. That is the same perspective we are shown in archaeological diagrams, and in museums, where tiny model cities sit in perspex cases. Like many children I found these dioramas endlessly fascinating, their people fixed in carefully composed narratives as they milled around giant masses of masonry and stone. These tiny versions of ancient worlds felt so powerful because they contained enough space for wandering. You could easily stare at one for an hour, figuring out the pathways and passages, discovering figures and patterns that suggested stories waiting to be told. Though they are fictional in the extreme, these dioramas often felt to me like a powerful way to explore history freely, without the stringent rules of study or research.

Swooping above Assassin's Creed Origins as Senu, I felt this same feeling re-emerging in some new and incredible form. Like the progression from staring at real architecture to climbing its virtual facsimile, this was a progression from a diorama of historical still-life to one of a living world. Preserved here, in this strange virtual place, within in a distorted image of an ancient world now lost, was an endless diorama, a place to wander and somehow connect to a sense of history. It might not be slavishly factual, or even physically accurate, but as I crossed the desert to Giza on the wings of an eagle and saw Memphis rise out of a moonlit Nile, in a view no ancient Egyptian could have had, I felt some kind of wonder that perhaps didn't belong in a blockbuster about violent men and their endless bloody quests. And then, it was gone.