Florence is so much more than a love story

A spoilerific look at a new touchscreen gem.

Florence is a new and inventive visual novel for smartphones, and it's the latest game from Ken Wong, the lead designer on the original Monument Valley. It's out now on iOS for £2.99 and is coming soon to Android.

Please note: This article contains extensive spoilers for the plot of Florence.

Florence has fallen in love. Hasn't she? She must have. There has been the distant glimpse, the first encounter - painful, dizzying and memorable. There have been dates and tentative conversations and the first kiss and now she is moving in with her new boyfriend. It is time to place two people's shoes on the shoe rack, to combine kitchen clutter and toiletries and books and doodads and keepsakes. What a wonderful thing! And yet the Tetris, the human Tetris - it will not quite work. There is never quite enough space to make everything fit, to allow both people to be their complete selves. No. If people are truly their things - and in the shorthand of a game so driven by ingenious mechanical contrivances, people must often be their things here - there must be a way, right? This is a story about a blossoming relationship, isn't it? And so this must be a puzzle. How do we make it all fit?

If Florence is built of dozens of bright moments of cleverness, the single cleverest thing about it is that, while always maintaining a careful veneer of breezy synecdoche and superficiality, it refuses to settle for anything easy or trite more often than not. It's a romance, and it truly is the story of a blossoming relationship - but the romance is not as straightforward as it initially appears, and the relationship that eventually develops is far more interesting and satisfying and convincing that you might hope for at first. As the tension in that sequence with the shoe rack, the kitchen and the toiletries suggests, Florence is a game about finding the wrong answers as frequently as the right ones. It's a game about a relationship that doesn't work, but that, in its collapse, reveals another relationship with a lot more promise. I was dazzled by this game, delighted by its mechanical smarts, but I was also lifted by its refusal, for so much of its running time, to conform to the most standard of all narratives.

Here is what Florence is about then. It is about a woman called Florence (encountered in that low, lost period in the mid-twenties) who you get to know through ritual. You watch her wake in the morning. You brush her teeth, swiping a finger back and forth across the touchscreen until the meter is filled. You follow her to work, prodding over the glossy surfaces of her social media as she jangles on the streetcar. These are theoretically intimate moments, but you are never allowed too close. You sit through a shift at the office, thick with the isolation of mindless, bloodless toil. "Some page of figures to be filed away;/--Till elevators drop us from our day..." You jab at the decline button on phone calls from her mother until you have to give in and answer, and then you select distancing things to say: clichés, cul-de-sacs, conversation-enders.

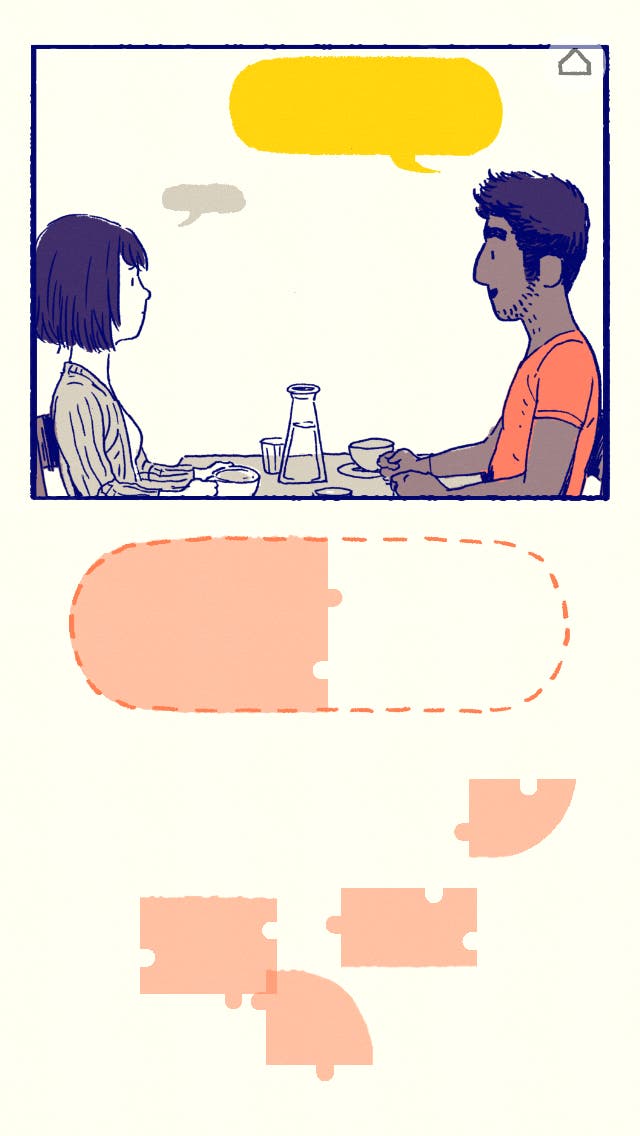

Florence wants to be in love, I think, and when she meets a busker everything seems to fit. Oh man, that meeting sequence is perfect! Then the date in which he speaks before you help Florence to reply, clipping together jigsaw speech bubbles to provide her half of the dialogue in a conversation that, true to form, you can never truly listen in on. Still, these people are perfect for each other, right? You hear about his dreams, to be a great cellist. You hear his music, which has already lifted Florence, note by note, through the streets towards him. You shake the Polaroids that develop as this new couple mints its first ideal memories. Every interaction - so clever, so brilliantly designed for a touchscreen - brings a new part of their life together into focus.

And then they break up. And I realise: of course they did. Of course they did! This is the real story, isn't it? The uneasiness, the tension behind everything. The dialogue we don't get to hear, but which still has so much to tell us, perhaps - of him leading the conversation while she tries to find the answers he is looking for. The dreams of success - his dreams, his success. There is grief here, but it is the grief you get at the end of something that was not quite right in the first place. It is sad that he is gone, perhaps, but sadder still that he was never the solution anyway, that he was not even close.

So what is the solution? Florence has one - the game and the person, because the game is the person really, even down to the polite distance at which the player remains. And yet, regardless of what this solution is, solutions of any kind were always going to be tricky here. So while I love the journey in Florence, I am not sure that even this better, more-satisfying-than-I-was-expecting ending that it lands on will really do. It trades one easy cliché for another, albeit, yes, a slightly richer one.

Florence is a game at odds with the easy conclusion, really, so when it settles for any kind of conclusion at all it has already pretty much programmed you to snip away at it a little, to find it elbowy and constrictive and trite.

But maybe that's the point. Maybe all conclusions are a form of settling.