The SD card and the vintage video game revolution

How modern technologies resurrected old consoles, and are now making them more powerful than ever

A conservative estimate puts the value of the entire Neo Geo library of games - all European, US and Japanese variants - at around a quarter of a million dollars. Some of the games are so scarce that they come up for sale only once a decade. In October 2009, for example, an anonymous buyer paid $55,045.64 for the European versions of the fighting game Kizuna Encounter and the football game Ultimate 11 (as if guided by a scriptwriter's pen, the buyer carried a custom-made briefcase to meet the seller, to ensure the games remained pristinely cosy on the flight home). There are, it is estimated, fewer than ten copies of each game in existence. Even for the wealthiest game fanatic, then, there is almost no opportunity to play these games anywhere outside of a PC emulator.

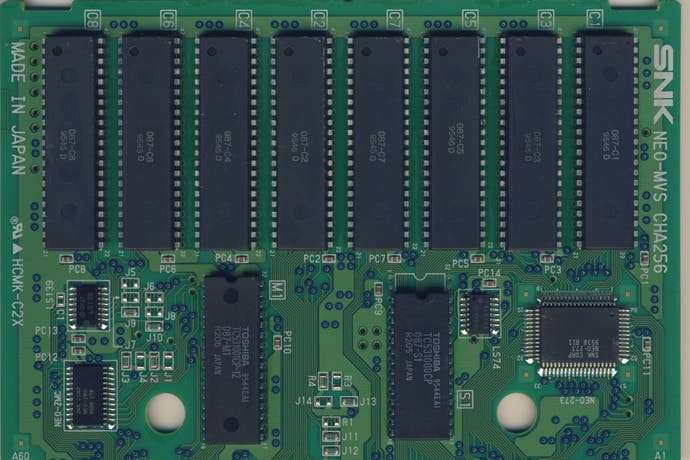

All this changed last year when a group of Spanish game enthusiasts released the NeoSD, a cartridge manufactured to look exactly like one of the chunky Neo Geo originals. As the name implies, the device, whose insides are studded with chips that replicate every foible of every game in the Neo Geo library, houses an SD card that can be loaded with a digital imprint of the entire Neo Geo collection (all 4.4 GB-worth of it), and slotted, with that pleasing, yielding clunk, into an original console. It takes around 30 seconds to load a ROM into the Flash memory, at which point the cartridge becomes utterly indistinguishable from the original.

At 435 Euros, the Neo SD is more expensive than a brand new PlayStation 4 Pro - and that's before you track down an original Neo Geo console on which to play the games. But despite the price-tag, the device sold out almost immediately. As four million sales of Nintendo's SNES Mini as well as the recent chart-flying success of Shadow of the Colossus show, the appetite to revisit old games and consoles has never been greater. We have entered the nascent stages of a vintage video game revolution, one fuelled by older video game players who are willing to pay stratospheric prices for products that both exhume and invigorate the past.

Take the W-Hydra for example, a luxurious $300 SCART input selector - of the kind that hasn't darkened a Curry's store shelf for more than a decade - that allows no fewer than sixteen consoles to be connected to a television without any loss of brightness or fidelity of image. Or the OSCC, a £160 device that re-introduces scan lines to contemporary TVs, fooling your brain into thinking that your pixel-thin high-end HDR-enabled set is, in fact, a handsomely fat 20-year-old CRT. Robert Fletcher, the founder of Retrogamingcables, hand builds scores of high-end cables designed for vintage video game consoles every month. After eight years of consecutive year-on-year growth, he now employs four full-time members of staff. Preorders for Fltecher's top-end 'Packapunch' cables always sell out on the first day of each week, after which he closes pre-orders while they're built. His backlog is now so great that he routinely closes the site to new orders for weeks at a time. Where once unscrupulous companies would release cheap bootleg versions of best-selling consoles for the grey market, now companies manufacture high-end, lavish "re-imaginings" of out-of-print hardware, such as the recently released, $189, Super NT. There is even evidence to be found on that most embattled of all fronts, the high street. Vintage Gamer, a specialist retro game store is just one of a handful of examples that have opened across the UK in recent years.

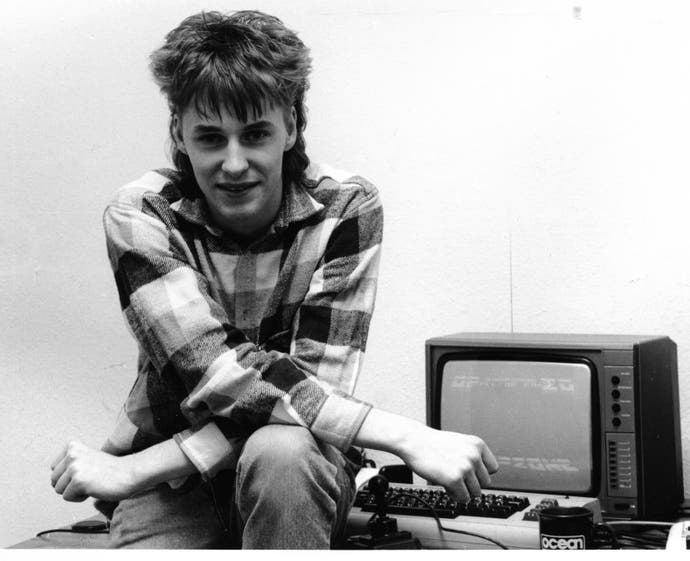

The revolution is more than a nostalgia trip. For those who grew up in a time before internet-enabled consoles, when games didn't rely on fragile servers, day-one patches, DLC upselling, and the gambling-adjacent business of loot crates, the pre-128 bit era may as well be an entirely different medium to that of the contemporary video game. "What we're seeing is games separating into a myriad of different sub-types that are not just gameplay or genre-based, but also era-based," says Jaz Rignall, who edited the formative video game magazine Mean Machines in the early 1990s. "Rather than old games and consoles being consigned to the cupboard, as they used to be, they're now being considered in the same way as music; they represent a style and an era that can be enjoyed by anyone who is interested in them."

Video games are constantly changing, forever lurching forward with each new iteration of console hardware. But, with a bit of distance and perspective, it seems as though the shift between the pre- and post-internet era video games was more significant and defining than anyone realised at the time. The urge to return to the past is practical as well as sentimental; they actually don't make 'em like they used.

34-year-old Igor Golubovskiy, better known by his fizzing online handle, Krikzz, is at the heart of the revolution. Golubovskiy grew up in Sumy, a chilly city in the North East of Ukraine. In 1993 his parents sent him on a programming course where he learned to write programs in BASIC on a Yamaha MSX2. As a reward the students were allowed to play games on the Japanese machine. In 1995, soon after this first, illicit contact, Golubovskiy convinced his grandfather to buy him a console, the Subor, a Chinese Famicom clone that, he says, was the only popular console in the post-Soviet states.

A few years later, Golubovskiy bought a second-hand Sega Mega Drive. Without any games to play on the machine, he had the idea to build a flash cartridge, one that could be loaded with digital copies of original games, and used to play them on the system. While Golubovskiy, who had skipped university to join a game studio (he was involved in porting some classic Sega titles like Space Harrier and Wonderboy to mobile phones), had taught himself electronics via internet tutorials, he was surprised at the scale of the challenge. "I had almost zero hardware skills at that time," he says. "I had to figure out how to fill a flash memory with data and connect it to the bus of the console, which was a huge challenge."

Having designed a rudimentary board for his Flashcart device, Golubovskiy placed an order with a small PCB manufacturer for four units - three to sell and one to keep. When they arrived, he placed the boards inside an old, hollowed out Mega Drive cartridge shell ("an old football, or basketball game - I can't remember which") and cut a small slot for an SD card into its side. He called the device the Sega Flashcart, a name that would later morph into the brand by which all his products are now known: the Everdrive.

When word got out about Golubovskiy's creation, he was inundated with requests to develop the project further. After a second revision (14 of which were produced), in March 2010, Golubovskiy launched the first official Everdrive. Other systems soon followed: one for the Sega Master System, the Game Gear, Nintendo 64, PC Engine. At first, Golubovskiy handled every aspect of the Everdrive's creation, from design and programming, through to production and shipping but as the business grew he was able to hire staff.

Today Golubovskiy, whose father is also an entrepreneur, handles only development tasks and, while he is the only programmer on staff, the company is poised to expand its "development department" in order to manufacturer more complicated Flash carts, and maybe even hardware. He sells seventeen different Everdrive products via an official online store (such is the Everdrive's success that eBay is awash with fakes) and, while Golubovskiy won't divulge how many cartridges he has sold during the past eight years, he says that he makes "good money" from work. "I am a retro video game addict," he says. "So I simply make products that I want to use myself."

The Everdrive's appeal is clear. As well as the chance to play vintage games with the original controller, rather than a misfit modern stand-in, using the original hardware eliminates all of the tiny discrepancies between even the finest-tuned emulator and the original hardware. Nintendo's NES and SNES Minis are essentially boxed emulators, rather than true recreations of the original consoles on which they're based, and therefore run games in ways that are different to the originals. A flash cart, by contrast, offers all the convenience of an emulator - a system's entire library of games at your fingertips - without compromise. "The cost of one of these products is often as cheap as one or two of the more expensive games, and there's the benefit of being able to play hacks, language translations and homebrew games too, as well as saving wear and tear on your original game," explains the 43-year-old YouTuber GadgetUK164. The commercial opportunity is obvious too; while the cost of living in Ukraine is less than that in most Western European countries, Golubovskiy isn't alone in being able to work fulltime on his project.

38-year-old Alejandro Romero had the idea for the NeoSD after he sold his invention, a GPRS device that could inform slot machine operators how much money was inside their gambling machines, thereby saving them a potentially pointless trip to collect non-existent winnings, to Cirsa Gaming Corporation, Spain's largest casino operator. Romero had long been a collector of Neo Geo arcade cartridges and wanted a way to play his games without opening the cabinet to swap out the games, potentially damaging his collection. Newly flush, Romero decided to spend his winnings, not on a sports car, but on building a Neo Geo Flash cartridge, and gathered a team of fellow enthusiasts.

"I wanted to make something totally solid, not to play pirated games, but something that would perfectly emulate the entire original Neo Geo cartridge hardware, without using tricks: a purist device, indistinguishable from the originals," he says. The first attempt, however, was a failure. Brabo's partner, intimidated by the technological challenge, pulled out. Part of the issue was the need to find a specialised programmer able to design Field Programmable Gate Array chips - a system that essentially replicate all of the circuity of a vintage games console in a single chip. The SNES Mini and most other emulators work 'sequentially'. This means they run, for example, a CPU instruction, then a graphics chip operation, then a sound operation in uick succession, causing miniscule timing issues and, sometimes, glitches. An FGPA chip, by contrast, allows all of the instructions to be processed in parallel, just as they were on the original console. "We knew the Neo Geo hardware intimately, but none of us had ever coded a FPGA," says Romero. "I made some calls, found a candidate, and, finally, put the financial resources behind the project."

The work was gruelling. As well analysing the original cartridges and their signals in order to properly understand how the various board revisions worked, the team had to marry current and outmoded technologies. "We quickly learned that making current electronics technology work with 25-year-old systems ago is supremely challenging," he says. The moment the first game successfully booted, six months in, was, he recalls, a "great collective experience", providing the team with enough momentum to push through the next twelve months of tinkering, principally to solve the complicated copy protection used on some later Neo Geo games.

"During the final months of development, we all agreed that working together was more fun than we expected," says Romero, who promptly left his lucrative job as an executive any Cirsa, to focus fully on high end vintage game projects, as a new company, Terranion. Profits from the venture have already funded a similar product for the PC Engine, released earlier this year, and 'pro' version of the Neo SD, which can store numerous games in Flash memory at once. "We are a small company doing things with ten percent of the staff that a corporation would use for the same work," says Romero. "For example, at my previous job there was a person whose sole responsibility was sourcing chips! We don't have anywhere close to that luxury. But we do have a clear plan for Terraonion, and we are currently laying the foundations to guarantee long-term success."

Romero's bet is, if the various lucrative industries that surround vintage cars, pinball machines, and musical instruments (the trade shows, the specialist repairers, the magazines and websites) sound. As a generation of players brought up on 8- and 16-bit machines enters their thirties and forties, the urge to preserve and return to those formative years and experiences will surely only intensify. The urge to revisit the past is quintessentially human. "Modern games reflect the complexity of modern life, whereas retro games reflect simpler times, our childhoods, and where imagination was a key part of the experience," says GadgetUK164. "Modern games provide extremely detailed immersive worlds, but there's something to be said for those simpler games from an era where imagination played an important part of the experience. When you have limited graphics and sound, the brain steps in and fills in the gaps."

Rignall, who, as editor of Mean Machines, assumed the role of the older, wiser, cooler brother to many young readers learning about the brave new frontiers of video games in the 1990s, gets closer to defining the indefinable appeal of the past than most. "Maybe it's just me," he says, "but I think that gaming just seemed to be a lot more exciting and surprising back then. That's not to say modern gaming isn't exciting. But things just felt fresh and new back then."