Playing today's games in a thousand years

A time traveller's guide.

Ask a young adult today what a floppy disk is and you'll likely earn puzzled silence. To them, they are ancient artefacts. Demonstrate an "old" game (say, from around 2000) to a kid today, and they might look at it with disbelieving curiosity. Did games really look like that, once upon a time, in the unfathomable recesses of antiquity? Similarly, to me, 30 years old, games of the early 90s (and the machines that run them) already exude a certain alien primitivity. Revisiting them several decades after their prime with a historian's curiosity is as fascinating as it is frustrating: it's easy to bounce off old games and their archaic workings.

The advance and change of technology is rapid, and, as many have pointed out, presents daunting problems regarding the preservation of older games. But there are other issues that may be less urgent, issues that are just as real. Let's assume for the sake of speculation that game historians and preservationists manage to address the problem, and that, say, a thousand years from now (if we're still around by then), at least a fraction of today's games will still be playable in some form.

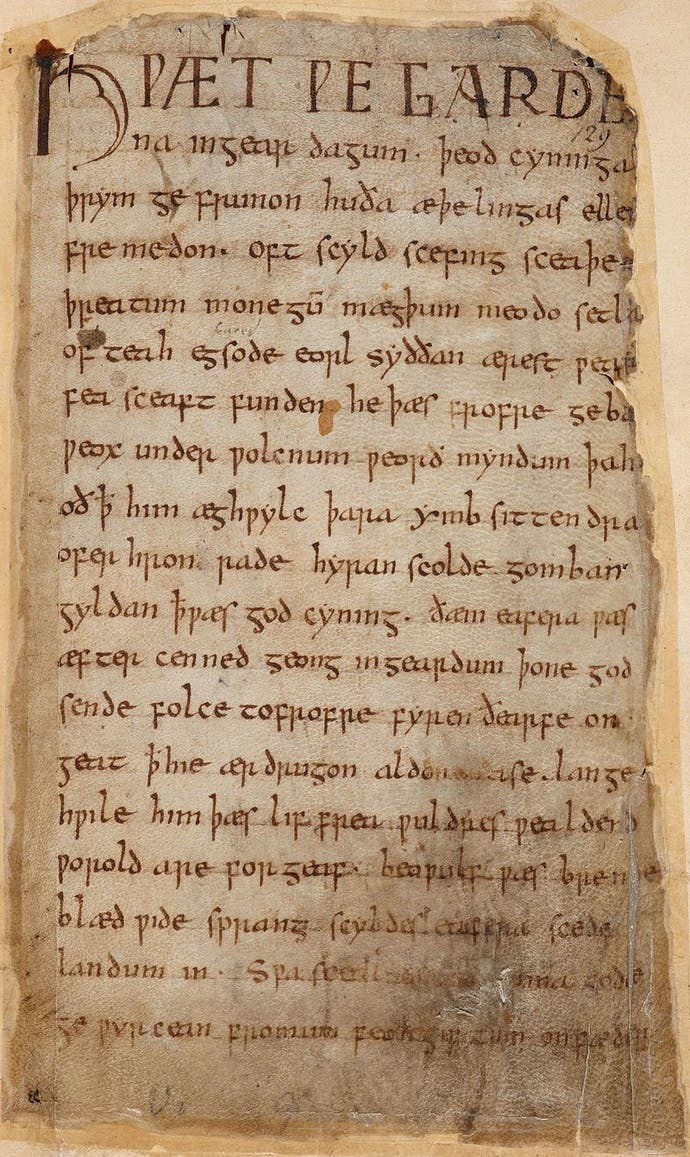

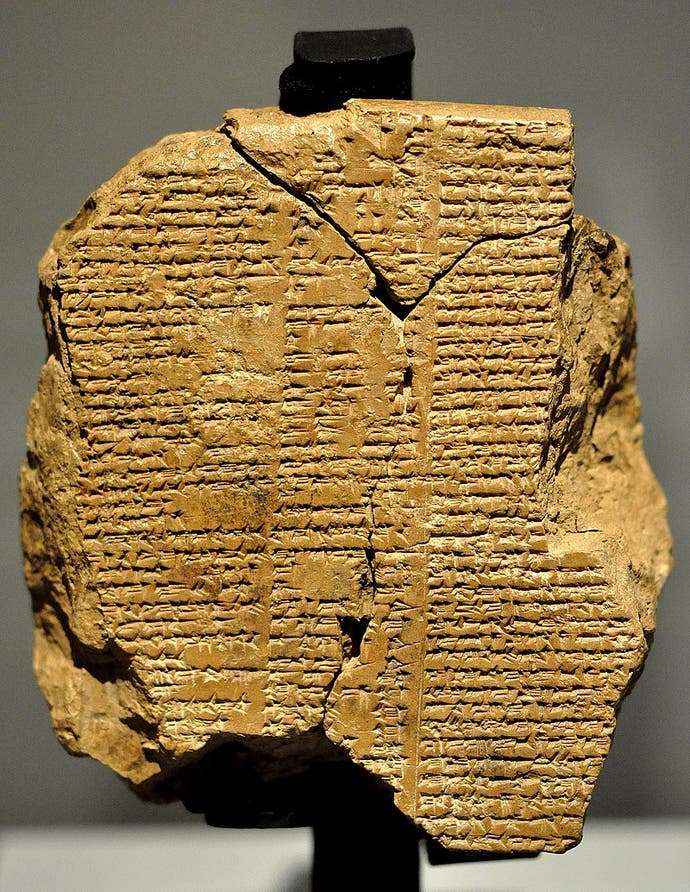

A thousand years may seem excessive. Given the breakneck cycles of hype and disinterest, of novelty and jadedness, surely no denizen of a future world a millennium from now will be interested in playing, say, Call of Duty: Infinite Warfare? But consider that when it comes to older media, literature first and foremost, some texts are still alive and well. You'll have no trouble finding a copy of Beowulf (ca. 1000 years old and surviving in a single manuscript which was almost destroyed in a fire in 1731), The Iliad (almost 3000 years old) or the Epic of Gilgamesh (a whopping 4000 years old). And it's not just historians who read them either.

Why these texts, and not others, have survived until now and achieved canon-hood if so many others have been discarded in the dustbin of history is a complex question that is also relevant for the preservation of video games. What is certain is that without the work of countless researchers and enthusiasts and their efforts to preserve, transcribe, reconstruct, translate, annotate and interpret these texts, they would be completely inaccessible to us today (even if the texts survived in material form).

Despite these gargantuan efforts, old texts can be a puzzle even to the people who study them. The controversial psychologist Julian Jaynes found the mentality behind works such as The Iliad or the Epic of Gilgamesh so alien that he dedicated an entire book, "The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind" (1977), to the bold thesis that people living roughly before the first millennium BC did not possess consciousness, at least not as we understand it today. Neal Stephenson's cyberpunk novel "Snow Crash" runs with the idea and reinterprets the Sumerian language (in which the Epic of Gilgamesh was originally composed) as a sort of programming language that can rewire the human brain. The "gibberish" of ancient texts, we are told, is fundamentally other, even quasi-magical.

Will today's games seem like gibberish to people living in a thousand years? There are a lot of factors that, if unaddressed, may make enjoyment of these games impossible. Some are peculiar to video games, which, unlike literature, demands constant physical input from players. Like the operation of machines, the playing of games requires fragile know-how that can be easily lost. This already begins with interfaces and controllers, which might quickly change beyond recognition. Anyone who's watched someone unfamiliar with games struggle desperately with this strange lump of electronics we call controllers knows that input devices are not at all intuitive, even if they feel like natural bodily extensions to those who've been playing for ages.

A few issues, however, games share with literature; the evolution of language especially. Will today's English still make sense to English speakers of the future? Will English still be around, or will we have adopted the lingua franca of our mutant lizard overlords? Language evolves alongside our rapidly changing world. New words, idioms and metaphors are constantly introduced to still be able to make sense of our environment. Future linguists and historians would have to find ways to translate, or at least annotate game texts.

And like literature, games refer to concepts or objects that seem natural to contemporaries like us, but will likely become obscure at some point in time. Going back just four centuries, Shakespeare's plays would be hard to grasp for anyone without at least some basic understanding of the society, customs, common cultural reference points (like The Iliad, for example), theatre practices and material culture of the Bard's day and age. The issue could be even more troublesome for games, since possibly alien concepts or objects aren't simply referenced, but may have to be interacted with. Imagine something simple like a ringing sound in a game. We will instantly recognise it as a mobile's ringtone and will go looking for its source. We know what phones sound and look like, and how to use them, but chances are that communication technology won't look the same a long time from now. Game worlds are full of references to our contemporary world, full of objects to use and manipulate, from the loot we pick up or the vehicles we drive to weapons and other tools. Today, even a child will have no trouble understanding these interactions. In a thousand years, we may need a host of researchers to make sense of them.

The visual language of games, too, only seems intuitive to us because we (both as players and simply as contemporaries) have been immersed in a thick soup of conventions and metaphors for years and have thoroughly absorbed it into our systems. Hearts as a health gauge. A lightning bolt as a symbol for "Initiative". Flashing button prompts. Floating arrows in different colours and sizes for main and side objectives. Red for enemy (or health), green for friend (or stamina, experience points, poison status). Even the "S" floating above phone booths in Yakuza 0 may prove confusing. What does it mean to "save" your game? And what the hell's a pay phone? (We won't have to wait a thousand years for that question to arise). While each element on its own may seems easy enough to puzzle out, they can easily overwhelm when assailing the senses in full force (not least because many games are designed with sensory overload in mind). The same soup that nourished us might turn out to be a treacherous swamp for a time-traveller visiting us from the future.

Even though some parts of mainstream culture still deny the fact, games do not exist in a vacuum, and are in fact inextricably embedded in a dense web of cultural and intertextual relations. Take Dark Souls, for example. Imagine attempting to play it without recourse to some basic knowledge about the tradition of fantasy fiction, from Arthurian myths to Tolkien and beyond, of which it is a part. Imagine playing it without ever having played another RPG or dungeon crawler (most of which might not have survived), or without understanding the tension between western and Japanese traditions and sensibilities. We may consider Dark Souls a masterpiece, but this will mean nothing if much of its context is lost or simply unknown to players trying to re-experience its magic in the far future. Uprooted by the turbulent flow of time from the soil that sustained them, individual games may well wither and die.

If we take another step back to see the bigger picture, it becomes clear that even the fundamental logic that underlies games may one day become a puzzle, especially if we consider that human nature isn't quite as fixed or "natural" as we often pretend it is. If one day our distant descendants are all connected in a collective hive-mind, perhaps games driven by competition and the clash between the motivations of individuals will make no sense at all. And we don't have to indulge in utopian naivety to imagine societies that will eventually have managed to disentangle themselves from the excesses and exploitations of colonialism, neo-liberalism and militarism. The citizens of this speculative future may not share our fantasies of domination, conquest and the endless accumulation of resources modern games often pander to. The chase after high scores, the empire-building of Civilization, or even the quasi-kleptomaniac obsession with collectables in games such as Super Mario Odyssey (grab all the coins!) may not resonate at all in a society with very different cultural or economic underpinnings.

Without time machines to go check, of course, all of this remains speculation. Will there still be people around who'll appreciate, or at least try to understand, the seemingly timeless appeal of Dark Souls, Doom, Civilization or Super Mario in a thousand years? The only certainty is there will be major hurdles beyond purely technological ones to overcome if anyone is to actually play and engage with these games in any meaningful way. As long as humanity stays alive and curious about the more playful aspects of its past, perhaps at least some of the games we play today will be still around by the time we're all long gone.