The impossible architecture of video games

Bang head against wall of text.

There is a saying in architecture that no building is unbuildable, only unbuilt. Structures may be impossible in the here and now, but have the potential to exist given enough time or technological development: a futuristic cityscape, a spacefaring megastructure, the ruins of an alien civilisation. However, there are also buildings that defy the physical laws of space. It is not an issue that they could not exist, but that they should not. Their forms bend and warp in unthinkable ways; dream-like structures that push spatial logic to its breaking point.

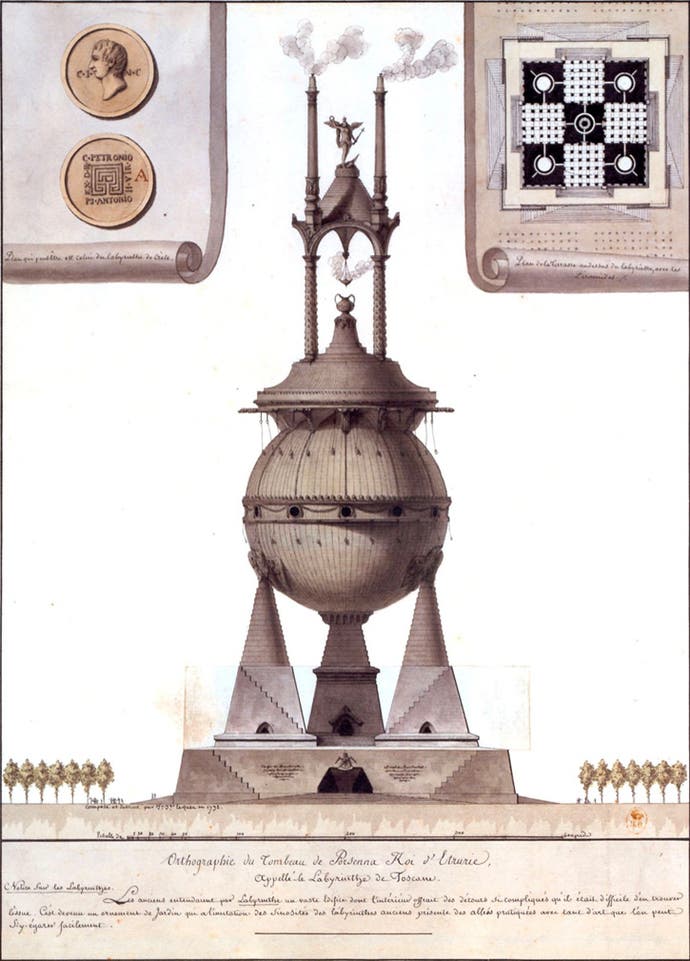

The Tomb of Porsena is a legendary monument built to house the body of an Etruscan king. 400 years after its construction, the Roman scholar Varro gave a detailed description of the ancient structure. A giant stone base rose 50 feet high, beneath it lay an "inextricable labyrinth", and atop it sat five pyramids. Above this was a brass sphere, four more pyramids, a platform and then a final five pyramids. The image painted by Varro, one of shapes stacked upon shapes, seems like a wild exaggeration. Despite this, Varro's fanciful description sparked the imaginations of countless architects over the centuries. The tomb was an enigma, and yet the difficulty in conceptualising it, and the vision behind it, was fascinating. On paper artists were free to realise its potential. If paper liberated minds, the screen can surely open up further possibilities. There's no shortage of visionary structures within the virtual spaces of video games. These are strange buildings that ask us to imagine worlds radically different to our own.

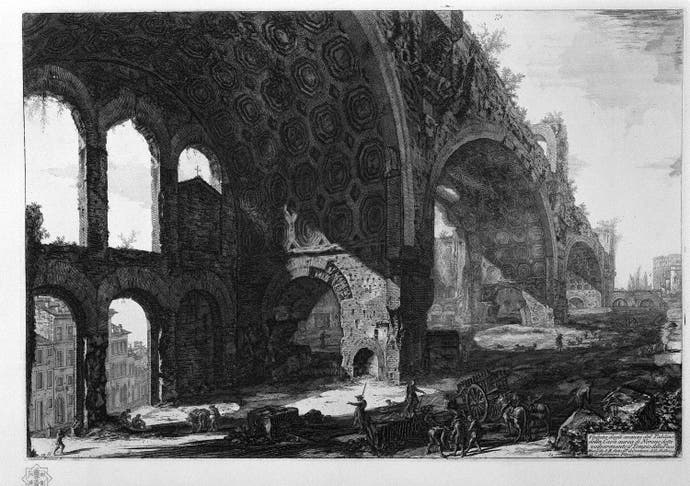

Whilst many impossible formulations are orientated towards the future, there are also plenty from the past. The castle in Ico is one example of this. During the Renaissance, Europe was obsessed, not with future utopias, but with ancient Greece and Rome. While the box art of Ico is famously inspired by Giorgio de Chirico, the long shadows and sun-bleached stone walls only make-up a portion of the game's mood. It is the etchings of Giovanni Piranesi that best capture what it's like to explore the castle's winding stairs and bridges. Piranesi's imaginary Roman reconstructions were absurdly big - so colossal you could get lost in just the foundations. In a similar way, Ico's castle is impossibly large, the camera zooming out in order to overwhelm you and build up the unfathomable mystery of its origin and purpose.

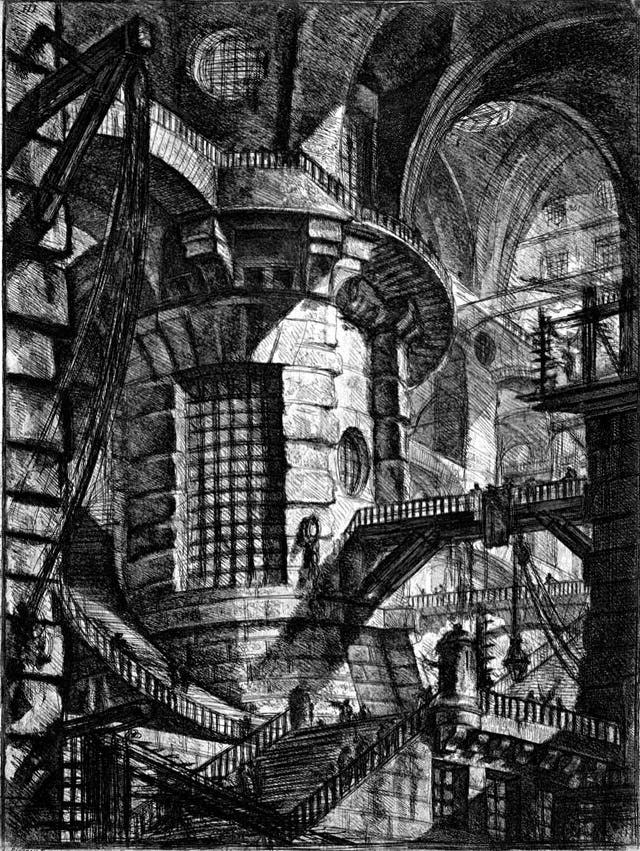

Piranesi is most famous for his "Imaginary Prisons". Unleashed from history, the etchings depict a vast subterranean network of walkways, bridges, arches and stairs. A labyrinthine catacomb filled with all kinds of infernal-looking machinery: wheels, cables, pulleys, levers. These were the Gothic nightmares opium-addled Romantics would dream up centuries later. Whilst Team Ico's Fumito Ueda has acknowledged Piranesi as an influence, the architect's visions extend further.

It's not hard to pick out the similarities between Piranesi's oppressive prisons and your typical FromSoftware gauntlet. With traps and lifts powered by ancient machinery and maze-like areas where platforms criss-cross and intersect within a cavernous space, FromSoft's environments mesmerise and disorient in familiar ways.

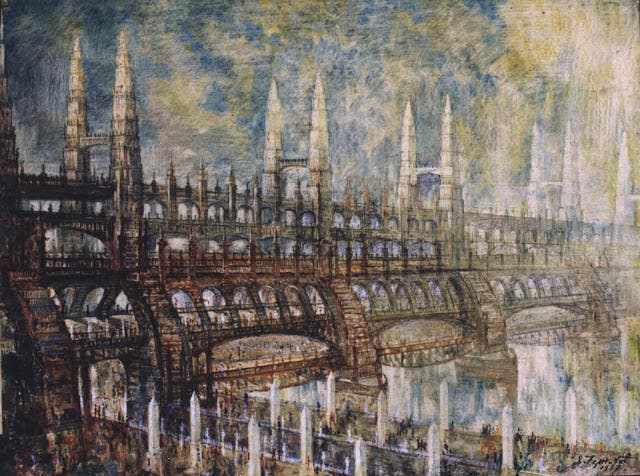

The environments of Dark Souls and Bloodborne also bear a resemblance to the work of Soviet constructivist Yakov Chernikhov. His early work was all sleek, coloured lines and elegant abstractions - a million miles away from ornate Gothic revivalism. However, as World War 2 loomed and Stalin tightened his grip on the Soviet Union, Chernikhov was forced away from the avant-garde. In private, his architectural fantasies took on darker shades. The endless cathedral spires and buttresses of places like Anor Londo, Yharnam and Lothric are very much reminiscent of this late work.

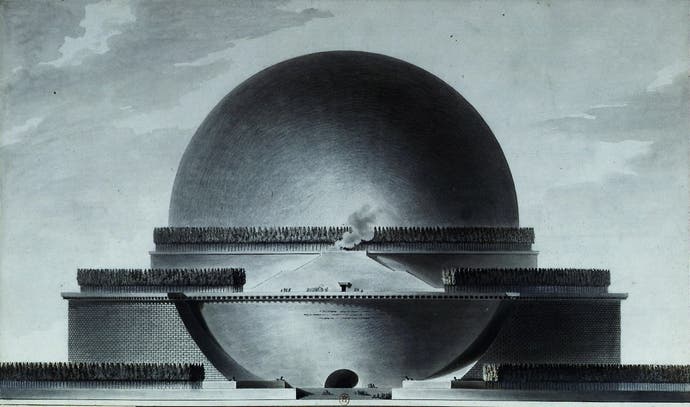

Many impossible structures are oriented towards the future. Étienne-Louis Boullée was one of several French architects working within the revolutionary period. His method was simple: geometry at an impossible scale. Boullée's pyramids and spheres are like great science fiction structures - all space stations and alien monoliths. Boullée, alongside contemporaries like Ledoux and Lequeu, imagined buildings on a cosmic scale. Glimpses of their monumental designs can be seen in everything from the ringworld of Halo to Destiny's orb-like Traveler. We also see spheres used in similar ways in futuristic titles like Obduction, No Man's Sky and The Signal From Tölva. These empyrean shapes, bearing neither ornament or culture, seem to gesture towards some transcendental truth. Like so many impossible structures, the forms create a distant sense of grandeur. This is architecture as alienation - forces so large they become humbling.

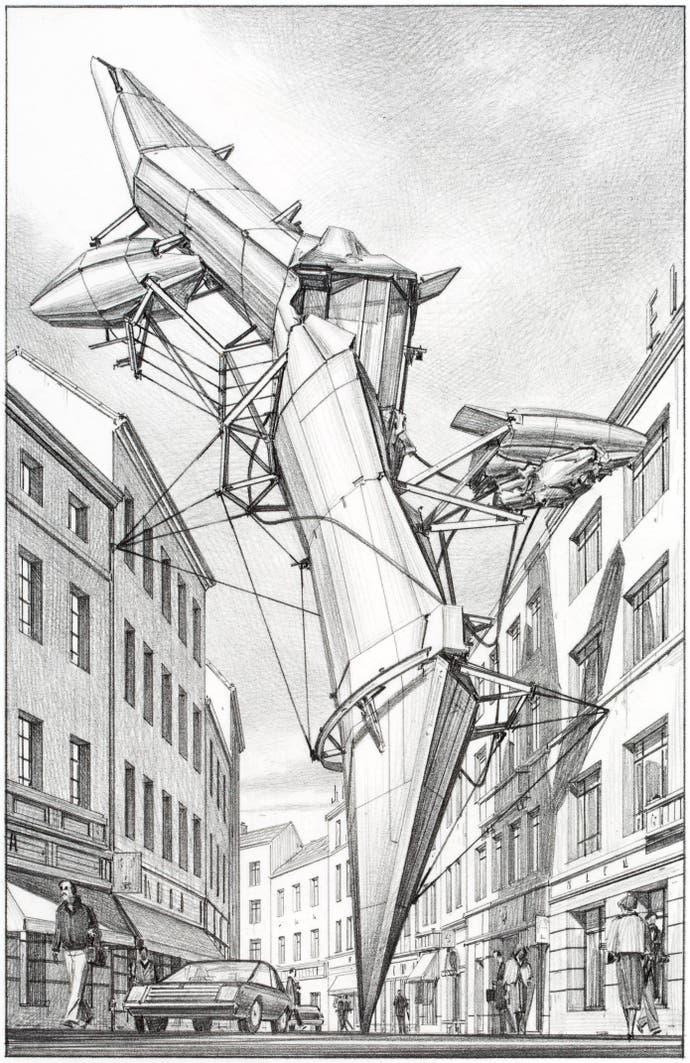

Another great science-fiction environment is Half-Life 2's City 17. Its central citadel is so tall it disappears into the heavens, but more important is the way in which the tower's influence creeps outwards, absorbing and re-molding the city in its image. This has parallels with the visionary architect Lebbeus Woods, whose philosophy was "Architecture is war. War is architecture". His visions were of a form of creative destruction. Out of chaos could spring newly invigorated forms. Half-Life 2 leans on the dystopian quality of this idea, but the Combine's infectious architecture is no less arresting.

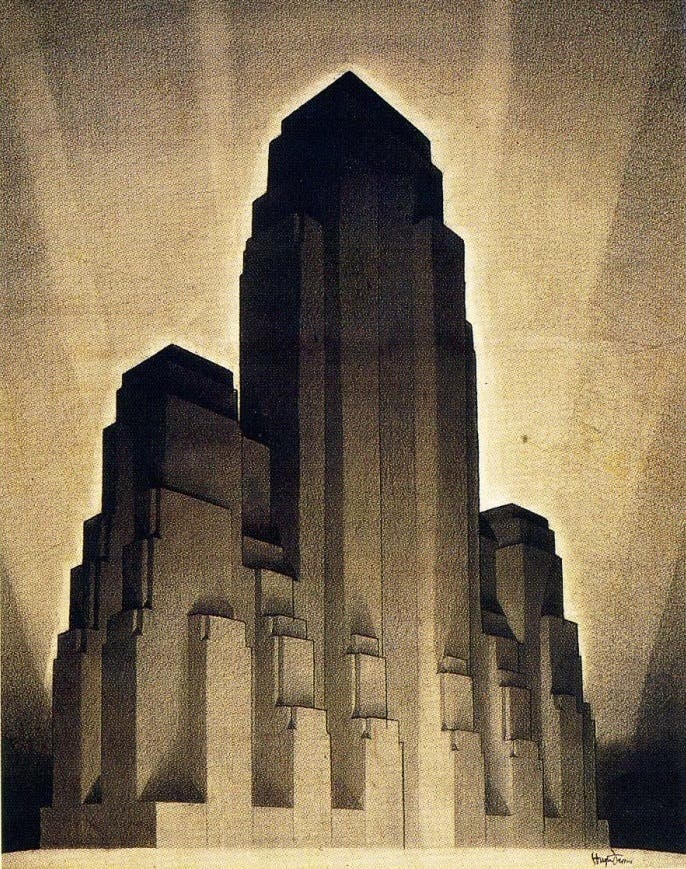

Impossible architecture is often bound up with the city, and Bioshock's Rapture is one of gaming's most iconic examples of this. While its submarine status renders it an unlikely prospect from the get go, the city has other visionary qualities. The Art Deco-inflected cityscape can be aligned with other speculative metropolises, including the one from the 1927 film Metropolis. Both drew inspiration from early 20th century Manhattan, which director Fritz Lang described as a "vertical sail, scintillating and very light, a luxurious backdrop, suspended in the dark sky to dazzle, distract and hypnotise". This same set of influences also inspired the architect Hugh Ferriss' "Metropolis of Tomorrow". All three cities are a mix of modernist sprawl and the gothic. Similarly, Rapture's skyscrapers loom impossibly large, dazzling with their searchlights and electric advertisements.

Whilst the structures explored thus far have been imaginative, there are also plenty of examples of the truly bizarre. Think of the shift from Dishonored's cities to "The Void" - a cold and fragmentary dreamscape. Pieces of Dunwall and Karnaca are chopped up and spliced with shards of obsidian, creating estranging forms. While Arkane designed an entire alternate dimension, other games distort their worlds in short bursts.

1998 was a landmark year for contorted corridors, with the release of both Zelda: Ocarina of Time and Thief: The Dark Project. 2018's DUSK uses the same trick in homage, its crooked passageway a jumping off point for the ordinary, where space is turned upside down. DUSK transitions from the aptly named "Escher Labs" to places like a facility in the sky, an underground cathedral and an entire city that cannot be named, altogether shattering concepts of space and time.

Independent games are very much the advanced guard of impossible architecture. Games like the Stanley Parable and Antichamber show off the mind-bending possibilities of experimenting with space and reconfiguring architecture on the fly. The artist M.C. Escher is obviously influential in this regard, as are concepts of non-euclidean geometry, strange topologies and hidden dimensions. Among all this weirdness lies the potential for horror, and games like NaissanceE and Kairo are keen to use architecture to make us feel insignificant. In a more extreme fashion, Echo plays with ideas of the uncanny and infinity, its gaping palace halls stretching off into the distance as if its designers fell asleep on the copy and paste command. Games like Anatomy and even the eerily-deleted P.T. also play with uncanny configurations, coiling domestic space into irrational shapes.

There's huge potential going forward. Despite having the uncanny ability to realise the impossible, too many games - particularly the big budget ones - play it safe when it comes to designing environments. With such a wealth of visionary architecture to be used as inspiration, on top of the sheer spatial possibilities, let's hope we'll see a lot more of the impossible in the future.