Hands-on with Oculus Rift DK2

The second-gen developer kit under the microscope.

The Oculus Rift DK2 is a development kit, not a retail product. Oculus VR is adamant about that. When you order one, you have to tick a box saying you understand that you're not buying something intended for consumers. In a quaint touch, you even have to name your current project when you sign up to the developer resource. We can't help but wonder how many people out there are working on 'playing the Elite Dangerous Beta'?

In spite of all this, the Oculus DK2 is, for many reasons, a much more practical, usable head mounted display than its proof-of-concept predecessor, the DK1. That's partly down to the headline hardware features: a higher resolution, low persistence OLED screen and positional tracking via a separate infra-red camera. The other half of the story is the 0.4 software development kit, which introduces several smart tweaks that improve performance and usability.

Let's start with that screen, though. It's been specifically chosen for VR use this time around - and the resolution is only part of the story. The 1920x1080 panel uses Samsung's PenTile technology, which sub-divides pixels into their component RGB colours. The upshot is that the 'screen door effect' of the DK1 - where the gaps between pixels created what looked like a black mesh across the image - is far less pronounced. Careful scrutiny reveals some diagonal hatching, and focusing on items far in the virtual distance is still problematic, but during play the effect is more like newsprint half-tone than a screen door.

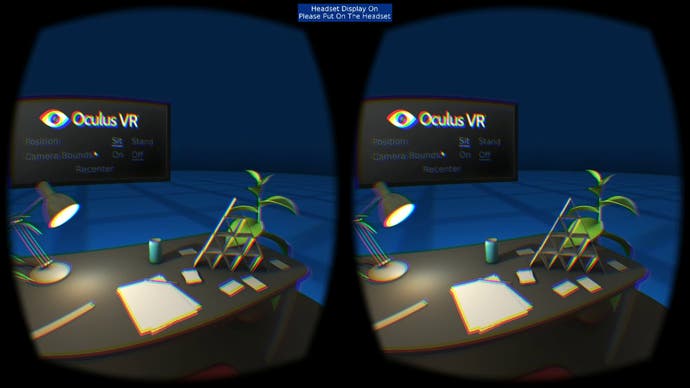

The other major benefit of this OLED panel is its low persistence, which is a major factor in reducing nausea for those affected by it in DK1. Gone is the soupy mess when you rapidly move your head, replaced by a crisp, responsive image that allows your eyeballs to track objects just as they would in real life. There's still some slight ghosting of very light or white objects on dark backgrounds, such as the text in the Oculus' own demo scene, but it's barely perceptible.

The second piece of good news for those whose stomachs rebel against VR is the DK2's 75Hz refresh rate, though this introduces some problems of its own. Naturally, an increased update means less disparity between actual head orientation and the frame rendered on the screen, but currently the most compatible of the DK2's two display modes is the extended desktop mode. Unless you're running the Rift as your default display, which is fiddly for navigating Windows, it locks to the frequency of your monitor, usually introducing a violent juddering effect that has you reaching for the sick bag almost instantly.

Get things running and you'll be faced with a more old fashioned problem - system horsepower. In order to benefit from the 75Hz display, you really need your games to be running at a rock-solid 75 frames per second, which is a non-trivial achievement. Graphically minimalist apps like Titans of Space ably demonstrate the brilliance of best-case performance, but more intensive games like Project Cars - which we've already seen referred to as 'the Crysis of VR' - will need to be dialled back considerably from detail settings that might be perfectly playable on a monitor.

Get everything working in concert, though, and behaviours that provoked nausea with DK1 are perfectly fine with DK2. The resolution is by no means perfect, but it's markedly superior to the previous model and basic teething problems like text legibility are all but a thing of the past. In practical terms, this means longer game sessions and the prospect of actually playing games to completion entirely within VR rather than just booting them up for brief test runs.

Finally there's positional tracking, which debuted on Oculus VR's internal Crystal Cove prototype. It's largely unchanged from a technological perspective, but it's an absolutely necessary inclusion. While initially the novelty of peering closely at virtual objects like racing car instrument panels seems to be the major appeal, in reality it's the more subtle sense of immersion full neck movement offers that is the long-term gain. The only potential speedbump later down the line is that currently, the 60Hz positional tracking of the infra-red camera lags substantially behind the 1000Hz update rate of the orientation sensors and, crucially, the 75Hz screen.

With the hardware largely pulling its weight, the 0.4 SDK is the element that brings DK2 that much closer to being a consumer-viable product. Usability has clearly been a huge drive and a major component of that is the new Direct to Rift display mode, which will likely supplant extended desktop mode by the time the first consumer version arrives. Deftly sidestepping problems like frequency mismatches and extended desktop juggling, Direct to Rift mode does exactly what it says on the tin - a separate executable file recognises the rift and pipes the visuals to the device. What this means is, rather than wrestling with connecting and disconnecting the Rift when switching between VR and regular gaming, the device can remain plugged in and at your beck and call. Currently getting things running on DK2 still feels hacky, but the smooth experience of Direct to Rift must be Oculus VR's intended future.

That march towards the future does involve discarding much of what was built for DK1. One of the most striking things about the DK2 in the weeks immediately after its release is how little is actually compatible with the device. Nothing built for the previous SDK works out of the box and while there are developers working on backwards compatibility for DK1 apps the message is clear - DK1 and even DK2 are just work-in-progress prototypes on the way to the consumer product. However, most developers are still engaged enough that they're prepared to port their work to the newer SDK.

Other fringe benefits of SDK 0.4 include better chromatic aberration correction, which accounts for the way colours separate as they are distorted through the two lenses. Again, light or white colours on dark backgrounds can be problematic, but in general the image resolves beautifully. The other key element, John Carmack's most high profile piece of programming 'magic', is less easy to identify by eye.

Timewarping, as it's known, is a second polling of the headset's orientation sensor after the frame has been drawn but just before it is displayed, reprojecting that frame to account for any slight change in orientation. It's a typically elegant Carmack solution to the problem of tracking latency, and definitely helps during frame-rate drops, but at the recommended 75fps, that latency is barely perceptible anyway. It's definitely by no means a crutch for systems struggling the DK2's higher performance requirements.

Oculus VR refuses to be drawn on how close CV1 (Consumer Version 1) will be to this unit's specification, but we're anticipating a far smaller leap forward than the one DK2 represents over the Kickstarted prototype. One thing is certain - the performance requirements of even the DK2 lend some credence to Oculus VR and Valve's assertions that the future of virtual reality is on the PC. A 1080p screen is absolutely an improvement on DK1's, but it's just as obvious that another increase in resolution would be hugely beneficial.

If, as is speculated, CV1 does boast a 1440p screen running at Valve's recommended 95Hz via DisplayPort, there'll be an almost exponential increase in the PC system requirement as both greater image fidelity and consistent, higher frame-rates are required all at once. A 1080p screen an inch away from your eyeballs is still the clear limiting factor - and actually lower graphical settings can often provide a more intelligible image on DK2 - but a higher resolution panel would be far less forgiving.

Alarming news perhaps for Sony, who will be relying entirely on the fixed specification of the PS4 to do the maths for Project Morpheus. But in our opinion, the DK2 is an important step forward: Oculus has made the step from an often nauseating novelty attraction to hardware on which most VR-enabled games are both adequately playable and comfortable for longer sessions. Morpheus appears to be targeting a similar specification to DK2, so there's little reason why that shouldn't be the case for Sony's retail HMD as well.

The real challenge from here onwards, it seems, is not necessarily in improving the specification. It's in designing games that are worth playing and tailored to the hardware's strengths and weaknesses - something that's far more uncertain than the 'Moore-esque' Law of ever-increasing resolutions and frequencies.