Titanfall tech interview

Digital Foundry talks with Respawn about the cloud, the beta, the day-one patch and more.

Last week, Electronic Arts contacted us asking whether we'd be interested in talking with Respawn lead engineer Richard Baker to discuss the more technical elements of its new gaming behemoth, Titanfall. It's sort of opportunity we can't ignore for obvious reasons, but as well as tackling the key technological issues, this was a chance to find out what went on behind the scenes in one of the year's most high-profile gaming events - the release of the Titanfall beta. Our vision of a networked hub flooding with incoming data turned out to be just one element of the developer's surveillance - Respawn was literally watching people playing its beta with an unexpected use of a recent revolution in gaming.

"Most of the guys here were watching Twitch TV a lot actually, seeing the expressions of the various people that were streaming while they were playing the beta, seeing what they were saying, watching what they did," Richard Baker tells us. "It's kind of great, like watching over their shoulders the first time they play the game. And lots of people were streaming, it was a different experience - sometimes people do things that you don't expect."

It's an interesting idea - direct observation of a vast number of people playing your game, complete with real-time feedback from even more observers. But beyond the audience reaction, this was a technological stress test - a means to put Microsoft's Azure cloud system through its paces.

"We had graphs of how many people were playing in different regions, which was kind of fun to watch, trying to get the player counts up but not too fast - it's an interesting mix," Baker recalls. "It was kind of exciting watching the graphs, looking at matchmaking on PC. I think we're going to do a lot of changes for how matchmaking works to try to make it so the games are a lot closer... We're still working on that, hopefully we'll be ready for launch, and we'll continue to improve after launch."

It's a new era in gaming. The ubiquity of the day-one patch has reduced the significance of sending off that gold master disc, and in the case of Titanfall - a game that can only be played online - some might even question whether the game was actually finished in the conventional sense at all. We were somewhat sceptical about the very short time period between the completion of the beta phase and the game's apparent completion. To what extent could the game be tweaked and improved based on the vast amount of feedback the beta would have generated? Baker acknowledges that the beta served as much as a demo for the game - a sampler to ramp up interest in Titanfall - as it was a means to stress-test the code, but he points out that a vast number of changes were made in situ.

"On the server side, we were changing things multiple times a day. It might not sound like a lot of time but we were able to respond to people actually banging on servers," says Baker. "And scalability... also stability issues - whenever there's an issue on a server, it pings an email to the company to find out why the server crashed... all those are very quick to fix. We fixed hundreds of issues in the beta."

"Most of the guys here were watching Twitch TV a lot actually, seeing the expressions of the various people that were streaming while they were playing the beta, seeing what they were saying, watching what they did."

What made the situation somewhat unique is that it was the first time that Microsoft's Azure cloud platform had really been stress-tested for gameplay. Respawn isn't making any grand claims about the cloud as a gateway to a next-gen nirvana ("In the end it's just a bunch of computer capacity. You can do anything with the cloud that you can do with a bunch of computers," says Baker) but it is a highly innovative approach to tackling the issue of multiplayer infrastructure which could open the door to a wider array of developers.

Rather than buying a whole bunch of dedicated servers, Titanfall accesses Microsoft's existing cloud network, with servers spooling up on demand. When there's no demand, those same servers will service Azure's existing customers. Client-side, Titanfall presents a dedicated server experience much like any other but from the developer and publisher perspective, the financials in launching an ambitious online game change radically.

"The biggest thing is that it allows people to take a little more risk. In the past you would have a game where you're like, 'OK, we have a game where we think we're going to get 10 million people play it day one,' and you buy a bunch of servers for day one... You need to have a lot of servers available to make the game super popular and, if not, you lose lots of money. On the opposite side, if you don't have a lot of servers on day one you're kind of screwed... Now nobody has to buy servers just in case they're going to be super-successful."

Titanfall may well be one of the most hyped and well-funded launches of 2014, but the implications here are intriguing - smaller developers can tap into the Azure infrastructure and don't have to take on the enormous financial burden of buying a server network with worldwide coverage. Bespoke server code created by the developer runs on Azure, and it could be tasked to do anything. In Respawn's case, it's a dedicated server, with trimmings - for example, running the AI cannon fodder drones that populate the levels. There is potential here for something more, and a mature network to make it happen. Perhaps the biggest revolution of Microsoft's cloud isn't game-changing graphics, but instead accessibility. The only question really is how much CPU resource is given to game creators - and did Respawn need to push Microsoft for functionality that simply wasn't present?

"We were mostly using local servers here while we were developing. We always want more CPU so there was a little going back and forth with Microsoft trying to get more CPU and to get the servers up faster," notes Baker.

Client-side, Respawn has based Titanfall on the Source engine, but it has effectively been re-built from the ground up. In our last Respawn interview, producer Drew McCoy said that "I hate to say that it's the Source Engine" because so much had changed. From our experience with the beta, we saw a piece of technology significantly transformed. Source was never particularly well-threaded, and there was no DirectX 11 support. More than that, the tech simply wasn't built for the kind of ultra-low latency feedback that the erstwhile Infinity Ward team members demand from a satisfying shooter.

"It's 64-bit obviously and we converted it to DX11 and part of the conversion gave us the opportunity to re-architect the engine and make it more like we wanted it to be on the memory side," Baker says.

"A lot of the work was making the engine multi-threaded. The original Source engine had a main thread that built up a command buffer for the render thread and there was a frame of delay. We kind of changed that so the render thread buffered commands as soon as they were issued - in the best case, it gets rid of a frame of latency there. And then almost every system has been made multi-threaded at this point. The networking is multi-threaded, the particle simulation is multi-threaded. The animation is multi-threaded - I could go on forever. The culling, the gathering of objects we're going to render is multi-threaded. It's across as many cores as you have."

The arrival of AMD's Mantle API has put a lot of focus on DirectX 11's API and driver overhead, and Respawn's solution to this is simple enough while highlighting that this is an issue developers need to work with.

"Currently we're running it so that we leave one discrete core free so that DX and the driver can let the CPU do its stuff. Originally we were using all the cores that were available - up to eight cores on a typical PC. We were fighting with the driver wanting to use the CPU whenever it wanted so we had to leave a core for the driver to do its stuff," Baker adds.

Going forward, the quest to parallelise the game's systems continues - particle rendering is set to get the multi-threaded treatment, while the physics code will be looked at again in order to get better synchronisation across multiple cores. We'll be seeing an interesting battle ahead in the PC space - the pure per-core throughput of Intel up against the more many-core approach championed by AMD. It's Baker's contention that games developed with Xbox One, PS4 and PC all in mind will see console optimisations result in better PC performance.

"Originally we weren't planning on an Xbox One version of the game. I'm certain that having an Xbox One version has made our PC version much better - it justified the effort in moving to DX11 and even 64-bit," Baker says. "I think in the future that's going to continue. The higher-end [graphics] cards are always going to be able to do more, but a lot of the bottlenecks - especially on PC - are more CPU and with DX11 you can have the GPU do a lot more that the CPU did previously."

Baker cites compute shader technology here, reeling off a list of examples where tasks traditionally run on CPU are instead run on the graphics hardware via DirectCompute. Bearing in mind the lack of DX11-only engines there were before next-gen console arrived, the transition to the newer API is welcome, and even older DX11-capable graphics cards should benefit. But Titanfall also sees one area where perhaps the vast unified memory of the consoles could have implications for the PC experience. At its very highest settings, the Titanfall beta's "insane" texture setting crippled performance on any GPU with less than 3GB of RAM. So what was the score there? Did "insane" mean something really bonkers, like running with completely uncompressed assets?

"No, we have a lot of high-res textures. We talked a lot about having some kind of mega-texture support or streaming but it's a multiplayer game, you drop in anywhere, you move around quickly," Baker says. "If we added streaming, we could use a lot less RAM for the same visual quality - if you were sitting still and looking in the same direction. But given that you're spinning around, wall-running and jumping through windows all over the place all the time, we didn't have a whole lot of confidence in texture-streaming without getting textures delayed a lot."

In the beta, ramping up texture quality to the insane level on a 2GB card could result in enormous "swapping" problems, with reduced performance as texture data switched between system DDR3 and GPU RAM.

"For the shipping game we've changed it quite a bit - what textures are various resolutions," explains Baker. "In the beta, if you switched it down one level below insane, all the textures were a quarter of the res."

Another performance worry was tackled with sheer disk space - the 48GB install has around 35GB of uncompressed audio. Most games use compressed sound files, but Respawn would rather spend CPU time on running the game as opposed to unpacking audio files on the fly. This isn't a problem on Xbox One - and wouldn't be on PlayStation 4 in theory - as the next-gen consoles have dedicated onboard media engines for handling compressed audio.

"On a higher PC it wouldn't be an issue," points out Baker. "On a medium or moderate PC, it wouldn't be an issue, it's that on a two-core [machine] with where our min spec is, we couldn't dedicate those resources to audio."

An optional download would have been our preference, but Respawn's philosophy appears to be all about keeping things as light as possible in order to service the gameplay. Titanfall doesn't have the same kind of advanced audio processing as Battlefield 4 or Killzone: Shadow Fall. It doesn't embrace computationally expensive deferred lighting solutions. The focus is entirely different: key to the firm's ethos is pursuit of low-latency controls, the best possible 'handshake' between the player and the game.

"People tend to trade a little more visual quality for more latency. It seems like everyone wants to give up the gameplay for slightly better visuals - especially on the PS3 games, there'd be a really long rendering chain," Baker muses.

"We're definitely biased much more the other way to make the frame appear as soon as possible. We actually changed how the networking works so the controls have less latency. And we changed how the main thread and the render thread works so that there's lower render latency speed. If we can get to a solid 60Hz, it's really responsive. Hopefully everyone will do it, and games will be more fun."

"Ideally it would have been a rock-solid 60 all the time when we shipped... we're still working to condense the systems, make them more parallel so we can hit 60 all the time, ideally."

Titanfall may have shipped, but from what Respawn is telling us, the game is still being tightened up and improved. Systems will continue to be optimised, hopefully yielding better overall performance, while there may be changes to the options available to PC owners - only hardware anti-aliasing is supported right now, but FXAA may be included too for those whose GPU resources are limited. Even those running higher-end GPUs could benefit here - for example, running the game at 4K resolution.

Respawn is also talking about what sounds rather like extensive Xbox One optimisations, including a revision for the 1408x792 native rendering resolution of the game on the Microsoft console.

"We've been experimenting with making it higher and lower. One of the big tricks is how much ESRAM we're going to use, so we're thinking of not using hardware MSAA and instead using FXAA to make it so we don't have to have this larger render target," Baker tells us. "We're going to experiment. The target is either 1080p non-anti-aliased or 900p with FXAA. We're trying to optimise... we don't want to give up anything for higher res. So far we're not 100 per cent happy with any of the options. We're still working on it. For day one it's not going to change. We're still looking at it for post-day one. We're likely to increase resolution after we ship."

The utilisation of 2x multi-sampling anti-aliasing is a lock for the initial rollout of the Xbox One code, and GPU optimisations are promised for smoother performance on the Microsoft console. As our beta analysis indicated, there's a long way to go there - Titanfall's frame-rate clearly falls short in the most intense action, which is really where the higher frame-rate is needed most in our opinion.

"A lot of the performance is on the GPU side. There's still room for optimisation and we're still working on it," Baker says. "Ideally it would have been a rock-solid 60 all the time when we shipped but obviously when there's big fights going on, lots of particle effects, lots of physics objects... we're still working to condense the systems, make them more parallel so we can hit 60 all the time, ideally."

Titanfall's '792p' resolution and frame-rate dips call into question - once again - the power of the Xbox One's hardware architecture. The GPU - based on AMD's Bonaire part - seems to be falling well short of the sort of performance we would expect from the architecture, making us wonder if the custom ESRAM is proving to be more of a problem than it should be.

"We're just trying to put as much trust in it as we can. It's an extra thing you have to manage but if it makes the game run better it's better than not having it, obviously," says Baker. "We've iterated on it - whether the shadow maps should be in there, whether it's better to have more render targets, whether some of the textures we use a lot should be in there. We played with it a lot and it definitely helps performance so if it wasn't there, it would be bad [laughs]."

It's known that Microsoft is attempting to free up precious graphics resources. Last year, the Xbox One architects told us that the GPU "time-slice" - the amount of processing time reserved by the operating system for elements like Kinect - would be made available to game developers. Respawn confirms that this hasn't happened yet.

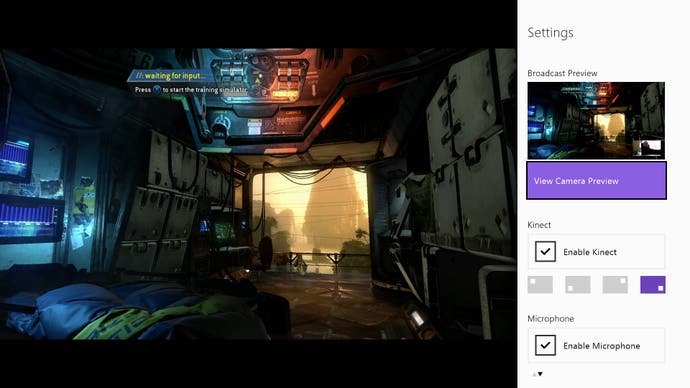

"Microsoft is heavily backing Titanfall to spur on Xbox One sales. The system software has been updated twice with the game's release in mind, and Twitch broadcasting is finally available."

"They were talking about having it available for launch and I think there were some issues for how it was going to work," Baker tells us. "It's not available for launch but we're definitely going to take advantage of that if they give that as an option. And the plan that is they will make that an option, so when it's visible we'll enable it for our game and we should be able to crank up resolution proportionally."

In the immediate future, there's a day-one patch for Titanfall, and while it's unlikely that we'll see much in the way of noticeable improvement for Xbox One over the beta, PC has received some interesting tweaks.

"We've reallocated video memory, so on video cards with less memory the apparent texture quality is higher. For weapons we used higher-res normal maps then for world geometry we used higher-res colour maps... which tend to give a better balance. We've tweaked some of the auto settings so the game looks better on various levels of video cards," Baker explains, before revealing that a prized game mode missing from the launch will be arriving soon.

"The main focus has been server issues, even on the client, fixing crashes. After we launch, everyone gets patches online so we'll continue to add features. We didn't ship with private match support but it's working here and we're going to patch that as soon as we can and continue to add whatever features are wanted by the community."

As our session with Baker comes to an end, it's time to address the great unknown. Just what is going on with the Xbox 360 version of the game? We wanted to know about resolution, frame-rate and feature parity. Two weeks from release and still nobody has seen the game.

"Yeah, we've actually been playing it almost every day here. Bluepoint's developing it and we've mostly been hands-off, letting them make their own technical decisions," he says. "It seems pretty close [in terms of] feature parity and they're still working on getting the frame-rate up. I'm not sure about the resolution..."

And at that point, our previously silent EA invigilator steps in: "There's nothing much more we can say."

Cut-off mid-flow, Baker chimes in with a final comment before the interview is over: "It's getting better every day."