Does resolution really matter?

Nielsen polling data says it does, but Digital Foundry isn't totally convinced.

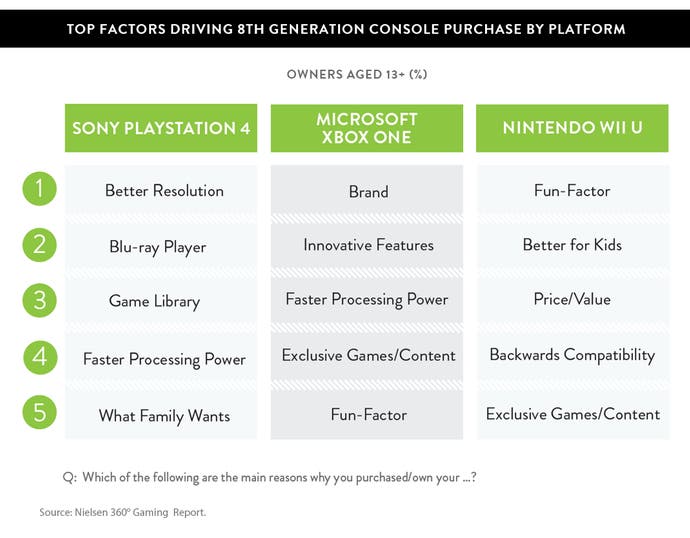

This one took us by surprise. A study undertaken by US pollmeisters Nielsen revealed this week that "better resolution" is the top reason people bought PlayStation 4 over its competition. It's a remarkable, perhaps even unbelievable result, and one we wanted to dig into more deeply, so we contacted the director of Nielsen Games, Nicole Pike, asking about the size and make-up of the sample and how respondents were directed into giving their answers.

Pike tells us that data for the report was collected using "Nielsen's proprietary, high-quality online panel in the United States". Two waves of data were collected, the first between November 7th and November 12th, 2014. The second came a couple of months later, from January 22nd to January 27th, 2015. In terms of the demographic make-up of each sample, wave one consisted of around 2,000 teens and adults aged over 13, along with 400 kids aged between six and 12. The second wave consisted of a further 2,000 teens/adults aged over 13.

"Post-survey, raw data was weighted to ensure representation of the US general population based on current US census data," Pike added.

Nielsen obviously knows what it's doing when it comes to its polling, but we were curious about how those surveyed chose their responses. It turns out that the pollsters put together a list of 30 reasons to choose from (of which "better resolution" was just one) and the following question was asked separately for each system they owned:

"You indicated that your household owns the following video game system(s). What are the main reasons for owning the following video game systems(s)? You can select as many or as few that you feel apply to each statement."

It all makes for fascinating reading. In an era where the relevancy of the specialist press is under scrutiny, we find that coverage of the resolution issue not just made it into the general public's consciousness - but also defined buying intentions, to the point where it was still considered an issue a whole year after the release of the current-gen consoles. Obviously this is our own personal interpretation, but our take on it is that resolution became a way of quantifying the technological capabilities of PlayStation 4 and Xbox One - a relatable metric, if you like. We're not sure if 'console A is more powerful than console B' was one of Nielsen's 30 reasons, but resolution is a parameter by which the differing power levels of the machines can be addressed, and was certainly the way the specialist press - ourselves included - went about it.

In some ways it's a grim state of affairs - especially for Microsoft - because as 2014 progressed, resolution as a meaningful, differentiating issue of the gameplay experience between multi-platform titles became less important. The amount of visually compromised 720p/792p titles appearing on Xbox One dwindled as the year progressed, while the 900p/1080p differential turned out to be much less pronounced than the raw maths suggested. Indeed, as the major titles rolled out in Q4, we saw resolution parity in key titles such as GTA 5, FIFA 15, Destiny and Assassin's Creed Unity. On other tentpole games like Far Cry 4 and Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare, PS4 maintained a resolution advantage, but raw pixel count wasn't the most crucial element of image quality (though it played much more of a role in the multiplayer portion of COD).

The question of whether resolution actually matters is explored nicely in GameSpot's recent Reality Check video, in which Cam Robinson oversees a 'blind taste test' of sorts across three platforms - PS4, Xbox One and PC. Far Cry 4 and COD are the main examples here, illustrating that despite a yawning chasm in resolution between PS4 and Xbox One, it's very hard for the majority of those participating to tell any difference in actual gameplay conditions. What's crucial in this case is that not only are both COD and Far Cry 4's res reductions well-handled on Xbox One, they also have performance profiles equivalent to or even better than their PS4 counterparts - and we're firmly of the belief that frame-rate difficulties have much more of an impact on the overall experience than resolution.

Robinson could have chosen titles where the difference is more pronounced - we would have enjoyed seeing the same test undertaken on the 720p vs 1080p Metal Gear Solid 5: Ground Zeroes, for example - but as an indicator for how close multi-platform titles are becoming, the games are well chosen. Call of Duty on Xbox One operates mostly at 1360x1080, yet looks remarkably close to the full HD PS4 version in motion. Similarly, Far Cry 4 runs at 1440x1080 on Xbox One, while again running at an uncompromised 1080p on the Sony console. The PS4 version is cleaner and more pleasing to our eyes, but not to a revelatory degree.

In the case of those two games, it's not so much the pixel count that is important as the ways and means by which the image is constructed. Advanced Warfare's campaign aims for a soft, filmic image, heavy on post-processing. Far Cry 4 uses a very promising anti-aliasing technique that blends post-process AA with additional resolution expertly blended in from previous frames still held in memory. Both games are using different technologies aimed at smoothing away the telltale signs of traditional rendering such as hard, geometric edges - elements that can look poor when upscaled. Both titles are also more forward-thinking in that they only scale in one direction rather than two, the idea being that upscaling artefacts are only evident on one axis, diminishing their impact on overall image quality.

But developers are thinking bigger. Working to eliminate resolution as a major consideration - or at least mitigating it - could revolutionise the realism found in current-gen video games. It's not exactly a new idea either.

"A few of us were chatting about what would we do... what could we do if we used next-gen hardware at standard def. What could we do?" Criterion, now Frostbite engineer Alex Fry told us back in 2010. "Interesting question. Lighting and quality of shaders and overall image quality that you get counts more than raw resolution or poly count."

In 2012, then-Nvidia, now Epic tech guru Timothy Lottes mused on his blog about how ultra-high detail video game art was at odds with the presentation found in movies. In short, Blu-rays may well process 1080p video streams, but pixel counts relative to video games are much lower.

"The industry status quo is to push ultra-high display resolution, ultra-high texture resolution, and ultra sharpness. In my opinion, a more interesting next-generation metric is, can an engine on an ultra high-end PC rendering at 720p look as real as a DVD quality movie?"

CG professionals - including Pixar's technical director Chris Horne, now at Oculus VR - weighed in:

"We do what is essentially MSAA. Then we do a lens distortion that makes the image incredibly soft (amongst other blooms/blurs/etc). Softness/noise/grain is part of film and something we often embrace. Jaggies we avoid like the plague and thus we anti-alias the crap out of our images," Horne added. "In the end it's still the same conclusion: games oversample versus film. I've always thought that film res was more than enough res. I don't know how you will get gamers to embrace a film aesthetic, but it shouldn't be impossible."

It's not impossible. In fact, it's happening. With titles like 2013's Ryse on Xbox One and the more recent efforts of Ready at Dawn with PlayStation 4's The Order: 1886, we have working examples of a similar kind of approach. These titles are both a clear evolution visually, and the good news is that they didn't need to drop down to DVD quality or even 720p. The Order uses around 74 per cent of the raw resolution found in a native 1080p framebuffer (using a 2.4:1 aspect ratio to avoid upscaling) while Ryse achieves its excellent visual results with just 69 per cent of a full HD pixel count. There's a strong argument that both of these titles represent the pinnacle of the visual arts on each of the current-gen console systems, despite the resolution trade-off.

Advanced anti-aliasing and naturally softer imagery is key, just as Chris Horne suggested: high frequency details are not the focus of the visual make-up - there's a more natural approach to the way in which materials are rendered. The Order: 1886 even uses the MSAA approach Horne advocates, in conjunction with other filters, though Ryse performs almost as well with a temporal form of SMAA post-processing. Does resolution matter? Well, with the recent release of Ryse on PC, we could finally compare its sub-native framebuffer to full 1080p, and the results are encouraging.

What you're seeing below is compressed video of course, but image quality on Xbox One holds up, as you can also see in our previous coverage. By far the biggest difference between the two streams comes down to performance, not image quality. Xbox One not only runs at a slower frame-rate, but its imagery is delivered in an inconsistent manner, resulting in further judder. However, Crytek's approach to filmic, more realistic rendering produces the most compelling evidence yet that it's not the amount of pixels you're rendering that matters, but rather what you do with them.

By removing resolution as most crucial factor in overall image quality, both PlayStation 4 and Xbox One games stand to benefit. GPU resources can be better spent elsewhere. With this approach in mind, you might expect diminishing returns on PC, though it's interesting to note that moving up to 4K can see a big improvement - similar to what you might expect from ultra-HD movie content. However, the horsepower required to make that leap is considerable.

Of course, not every game will use the filmic approach, but developers are still working to make resolution differentials less of an issue - even for the more traditional forms of video game rendering. Returning to Far Cry 4, its HRAA anti-aliasing technology targets the kind of aliasing that looks particularly noticeable when it's upscaled. Most post-process AA filters deal with jaggies just fine, but they can only consider the current frame, leading to discontinuity as each new image is processed - this results in the kind of pixel-crawl and sub-pixel break-up seen in many games. HRAA doesn't just anti-alias the image in the current render pipeline, it also seeks to address the temporal artefacts too, producing a cleaner, more consistent image. It doesn't just look good on static images, it works in motion too.

There's still a long way to go. In the greater scheme of things, it's still early days in the current console generation, and while progress in the visual arts has moved on significantly since Xbox One and PS4 launched, mitigating the resolution difference has mostly come about through improved scaling on Xbox One and heavier post-processing effect pipelines on certain titles. We've seen some promising results, but we're not out of the woods yet. Battlefield Hardline launches later this month with a 720p Xbox One resolution and unimpressive image quality as a result, while we suspect we'll see the same situation with Metal Gear Solid 5: The Phantom Pain later on in the year, if the Fox Engine titles released to date are any indication.

Those titles should be outliers though, and fingers crossed that across 2015 we'll see enough progress that next year's re-run of the Nielsen survey sees the quality of the gaming experience as the motivating factor behind investing in console hardware. In the meantime, perhaps the biggest takeaway from the survey data is that it's the Wii U owners that are having the most fun from their gaming hardware...