Can AMD's new strategy restore its fortunes?

The Radeon RX 480 offers excellent value - but what about the rest of the range?

Competition improves technology - we need plurality in the PC components market and we need alternatives to market giants Intel and Nvidia. In short, the bottom line is simple: we really need AMD to do well. This week's launch of the Radeon RX 480 demonstrates a new approach that marks a radical shift away from AMD's traditional release strategy. Gone are the toe-to-toe battles with Nvidia at the top tiers of PC performance - the green team currently has the premium market completely to itself. Now we see new Radeon technology employed in an all-out assault on the all-important price vs performance sweet spots in the graphics market.

According to AMD, 84 per cent of graphics card purchases are in the $100-$300 price segments. Now, that doesn't necessarily mean that the lion's share of the profits reside here, but a key part of AMD's new strategy is to reclaim overall market share. In this area, Nvidia's overall dominance is undeniable. AMD has clawed back some percentage points in recent times, but the overall outlook has generally seen an 80/20 split in Nvidia's favour. Unofficial, unverified figures we've seen have indicated that certain territories - the Nordics, for example - see the GeForce brand enjoy a 90 per cent market share.

In targeting the mainstream, AMD hopes to gain momentum, increase share and then move on to tackling the higher end of the market with its upcoming Vega products. But in the here and now, despite some teething issues on initial cards, the new Radeon RX 480 represents a good start in returning AMD to a much more competitive state.

As our RX 480 review this week stated, if you want better-than-console visual quality and 60fps gameplay, the RX 480 currently offers the best combination of price and performance, making it a compelling buy. Priced at £180/$199 (blame VAT and 'Brexit' on the closer-than-usual cost differential), the bottom line is this - the cost of building a PC that offers a substantial, must-have improvement over the console experience just got a whole lot cheaper.

At a press day this week in Munich, AMD shared more on its plans. Up until now, all we've known is that two chips are in production - Polaris 10 (the processor found in RX 480) and Polaris 11, a much smaller chip aimed at the entry-level desktop market and gaming notebooks.

Polaris actually represents an attempt to streamline AMD's mainstream GPU line-up: previously we had four different chips - Bonaire, Pitcairn, Tonga and Hawaii - proving the basis for six different products (R7 360, R7 370, R9 380/380X and R9 390/390X). Polaris 11 effectively replaces Bonaire and Pitcairn at the bottom end of the market by offering a specs bump to the low-end, while Polaris 10 straddles the performance envelope of the two higher-end parts. It's not as powerful as the fully enabled Hawaii in 390X, but it effectively matches the 390 and is much, much faster than the Tonga chip found in 380/380X.

A line-up of six products has been cut down to just three. In addition to RX 480, AMD has revealed the existence of two more GPUs - products we are set to learn more about in the next couple of weeks. We expect the RX 470 to hit the market swiftly - it looks physically identical to the RX 480, and it's based on the same Polaris 10 chip. However, only 32 of the available 36 compute units are enabled.

AMD isn't offering anything more on specs, though in a briefing we attended this week, chief gaming scientist Richard Huddy suggested a 2x performance improvement over Polaris 11. Assuming something in the region of four teraflops, we suspect that R7 470 will see clocks drop to 1.0/1.1GHz, and will feature slower GDDR5 - perhaps something in the region of 6gbps. Again, memory bandwidth stats were conspicuous by their absence in the AMD presentation - all we know is that 4GB of VRAM is a lock.

Based on the compute unit count (which matches the old Tonga chip) and efficiency enhancements, we should see performance higher than the outgoing R9 380 and 380X. This won't see a game-changing improvement over consoles in the way that RX 480 delivers, but there'll certainly be a useful boost. Price-wise, if AMD is looking to make as much of an impact as it did with RX 480, we would hope for a product in the region of $150 (UK pricing is very hard to guess given the current economic turmoil).

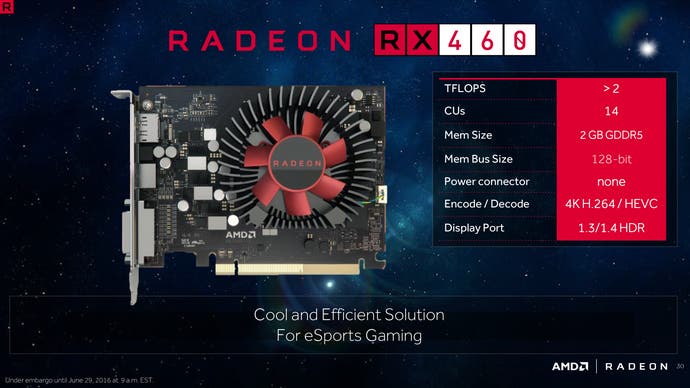

The final product in the line-up is the RX 460, which we expect to see at the $100 mark. This actually uses a cut-down version of the smaller Polaris 11, with 14 of the available 16 compute units active. Based on efficiency improvements, clock-speed increases and an additional two compute units up against the outgoing R7 360, this should be an interesting package, offering performance capable of inching ahead of PlayStation 4's GPU. The board itself is absolutely tiny - no additional PCI Express power cables are required - and it retains the full range of media encode/decode functions found on Polaris 10. In short, it could be a great product for HTPC home theatre set-ups.

As for the fully enabled Polaris 11 - we strongly suspect that the full 16 compute units will be enabled for a mobile chip for thin and light laptops. In the notebook space, clock-speeds need to drop in order to manage thermals, reduce power draw and conserve battery life: using the fully enabled chip will help here to offset the inevitable performance drop.

Overall, what's clear is that AMD has rationalised its mainstream offerings and it may well be as simple as having compelling desktop products at the key $99, $149 and $199 price-points. The question is to what extent the red team can make an impact here in the face of a rival in the form of Nvidia that gleefully revealed a $2bn investment in its new Pascal architecture - the kind of R&D budget that AMD simply doesn't have available.

At the press event, AMD made it perfectly clear that at their current top-end at least, they know that Nvidia is coming for them - and sooner, rather than later. The release of the GTX 1060 is the next logical step in Nvidia's release roll-out but what isn't known are full details on the processor design it is based on, and from there, the likely performance level plus the price-point (though leaks are starting to emerge).

From our perspective, the $199 ticket price is an important psychological factor in the success of RX 480 - a crucial component in defining its message. We have no doubt that Nvidia could match this price, but equally, the firm has enjoyed no shortage of success with GTX 1070 and GTX 1080, both of which saw significant price-hikes compared with their direct predecessors.

With its Maxwell and Pascal architectures, Nvidia has a proven track record in convincing users to spend more on their graphics upgrade by providing compelling performance. The question is whether the green team thinks the same strategy will work for the mainstream market - do they preserve margin with a faster, more expensive product or do they face down the new AMD hero product face-to-face at $199?

This particular battleground is going to be hard-fought, and there are some concerns about AMD's chances in competing with Nvidia here effectively at the base technological level. Both Polaris and Pascal designs are based on new, smaller, 3D 'FinFET' transistors. Power efficiency for AMD has improved over their old chips, but the RX 480 power consumption figures are disappointing overall, showing only a small improvement over Nvidia's older 28nm parts. Nvidia's new 16nm GTX 1070 commands Titan X levels of performance and draws less juice than RX 480, while operating with a frame-rate advantage typically in the region of 50 per cent in like-for-like tests. The power consumption figures in particular may have profound implications for AMD's plans in regaining market share in the laptop graphics market.

| RX 480 | R9 390 | GTX 970 | GTX 1070 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak System Power Draw | 271W | 437W | 295W | 263W |

There's also a patent disparity in terms of clock-speeds too. Nvidia's processors operate at 2.0-2.1GHz when overclocked to their limits, up by 500-600MHz from their 28nm equivalents. By contrast, we could only just break the 1.3GHz threshold with RX 480 - clock-speeds have only increased by around 200MHz compared to similar products from the last generation. And on top of that, there are revelations that in some scenarios, the RX 480 is pulling way too much power from both motherboard and PCI Express power lines. This is a cause for concern (AMD has released a statement and says this can be fixed in software (with details to follow on Tuesday) but in the meantime there remain concerns that cheaper motherboards may not be able to cope with the RX 480's current demands - not what you want to hear on a brand new product launch.

The obvious question to ask is this - what if AMD's strategy for the mainstream is a product of necessity based on the limitations it has encountered in dealing with the new, immature 14nm FinFET fabrication process? In short, is AMD's value proposition the best possible option it had available based on the quality of technology it could actually bring to market? AMD's shrewd targeting of the mainstream gamer sounds like a winning formula, but Nvidia has yet to play its cards - GTX 1060 is coming and if the impressive performance gains seen on GTX 1070/1080 filter down, RX 480 could be in for a hell of a challenge.

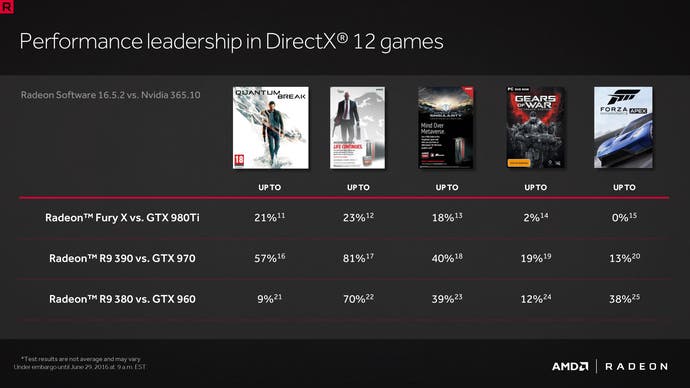

If this all sounds rather pessimistic in terms of AMD's longer term prospects, it should be balanced with areas of the Radeon technology that show evidence of clear advantages over Nvidia's technology. AMD is claiming performance leadership in DirectX 12 gaming - a massively important growth area - and has come up with the table below to demonstrate the extent of its domination.

Some of the performance claims here look outlandishly high - and GPU vendors are often highly selective in their data - but the bottom line is that Radeon's lead in Ashes of the Singularity is corroborated by virtually every independent benchmark, the Quantum Break figure ties in very closely with our own GTX 970 vs R9 390 tests, while our figures for Hitman on DX12 sees some phenomenal AMD performance, to the point where the same benchmark running on RX 480 at 1440p is only around 10 per cent slower than GTX 970's showing at 1080p.

As fast as Nvidia's Pascal technology is, questions still remain about the ability of the hardware to handle asynchronous compute as well as its AMD counterparts. And we should expect to see this feature more fully utilised as time goes on - already developers are using it to extract much more performance from their console titles. It's utilised extensively in id software's recent Doom reboot, to the point where team member Tiago Souza reckons the team clawed back three to five milliseconds of processing time - a massive help bearing in mind a 16ms render time for each frame.

This is not an isolated case either. Ubisoft's Mickael Gilabert claims 2.5-3ms savings in console Far Cry Primal, while Q Games' James McClaren claims 6-7ms savings at 30Hz, presumably on PS4 title The Tomorrow Children. As DirectX 12 and Vulkan slowly take over from DX11, this could have a profound effect on the performance differentials between Nvidia and AMD products. We intend to take a look at 'the story so far' on DX12 for the mainstream enthusiast PC gamer once we have both GTX 1060 and RX 480 in hand.

As things stand, AMD's new discrete graphics strategy is intriguing. We really like the RX 480 - it's not really about the benchmarks (as decent as they are), it's about the experience it provides: console-beating 1080p60 visuals at a highly appealing price-point. However, the power consumption issue needs to be comprehensively resolved as soon as possible, and there is a responsibility for journalists to re-evaluate the product's performance once the fix is out there - typically, less power means lower clocks resulting in a drop in performance. In terms of the rest of the line-up, until we're hands-on with RX 470 and RX 460, we can only 'guestimate' their performance credentials by extrapolating downwards from the 480, but our gut feeling here is that these are not 'sexy' products - the use-cases there are not quite so compelling, so it's going to be about offering great value: the price-points are going to have to be every bit as competitive as RX 480's.

But for a while at least, the only competition we can foresee from Nvidia against RX 470 and RX 460 will be iterations of existing 28nm parts - aggressive price-cuts on GTX 950/960 to bring them into line could be likely. But it's the upcoming RX 480 vs GTX 1060 face-off that will prove most compelling and will define which vendor offers the most value to the mainstream gamer - and we'll be there with the benchmarks and analysis as soon as we can.