Nvidia G-Sync: the end of screen-tear in PC gaming

Digital Foundry goes eyes-on with the revelatory new technology.

Nvidia has revealed new technology that eliminates screen-tear from PC gaming forever. Dubbed "G-Sync", it's a combination of a monitor upgrade working in concert with software that is exclusively available only from Nvidia's Kepler line of graphics cards. It's a phenomenal achievement that drew praise from three of the most celebrated names in video game technology: id software's John Carmack, Epic's Tim Sweeney and DICE's Johan Andersson, all of whom were on stage at Nvidia's reveal event to sing the praises of the new tech.

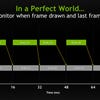

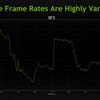

A fundamental problem facing gaming is that the monitor operates on a clock that is separate and distinct from your console or PC. On a typical 60Hz display, the screen refreshes every 16.66ms. If the games machine has a frame ready, it can synchronise with the display, but it absolutely needs to have the next frame ready in the next 16.67ms period, otherwise it will have to wait another 16.67ms for the next refresh. That's the fundamental problem with games that run with v-sync - if that time interval isn't met, judder creeps in.

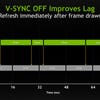

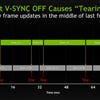

The alternative right now is to pump frames out to the display as soon as they are ready, mid-refresh. This causes a phenomenon we simply can't abide: screen-tear.

Various solutions have been attempted across the years. On console, the general trend is to lock at 30/60fps, and to drop v-sync when the frame-rate falls beneath, introducing screen-tear only when absolutely necessary. Other intriguing technologies - including frame-rate upscaling, which mimics the frame-rate smoothing effect seen on HDTVs - have also been investigated but haven't been implemented in a shipping game.

G-Sync solves the issue at a hardware level by allowing the GPU to take control of the timing on the monitor. Rather than locking to a set 16.67ms refresh, the screen kicks off its update when prompted by the GPU. The result is that there are no more duplicate frames rendered on-screen, meaning no judder. The screen refreshes according to the speed of the GPU, with maximum refresh on the Asus monitors we saw locked to a high bound of 144Hz.

"Developers are pushing new frontiers in rendering technology, but the way displays work have forced us either to accept immersion-killing v-sync judder or eye-rending screen-tear. G-Sync is the first serious attempt at tackling the issue."

Now, the big question here is: what about consistency? If the graphics card can refresh the screen whenever it wants, surely that has to be noticeable to a certain degree? Nvidia had two demos on show to illustrate how G-Sync works, and we were able to make a number of interesting observations about how the technology works in action. In order to illustrate G-Sync more effectively, two systems were set-up side by side - one with a traditional monitor, another right next door with G-Sync enabled. Both were running mid-range Kepler GPUs - specifically, the GTX 760.

The first demo took the form of a stone gazebo with a swinging pendulum in the middle. Zooming in on the pendulum we see some text. First up, we saw the demo operating at the optimal 60fps on both systems and the result was - as expected - identical. After that, the frame-rate was artificially lowered on the traditional system, first to 50fps, then to 40fps. The result was as expected: judder, caused by repeat frames being packed into the 60Hz time-frame. Then the same artificial frame-rate caps were introduced on the G-Sync system next door, the result being no perceptual difference in fluidity - the demo remained super-smooth.

After this, v-sync was disabled on the traditional system, causing annoying screen-tear at 50fps, and a cycling tear from top to bottom at 40fps that was simply unacceptable for anyone with even a passing interest in image integrity. The scene panned back, taking in the whole gazebo, after which the scene is spun, highlighting just bad screen-tear can be in fast-moving scenes with plenty of panning. Meanwhile, on the G-Sync side, the same frame-rate reductions caused no undue impact to fluidity at all. The same exercise was then repeated on both systems using the recent Tomb Raider reboot, the result being exactly the same: tearing and/or stutter on the traditional system, silky smooth fluidity with the G-Sync set-up.

"We did notice some minor ghosting on G-Sync when running well under 60fps, but it's a worthwhile trade-off if it means the end of screen-tear and judder."

So is G-Sync a magic bullet that kills screen-tear and judder with no side-effects whatsoever? The answer there is in the negative. The text on the pendulum in the gazebo demo was the giveaway - crystal-clear at 60fps on both systems, but with evidence of ghosting as the frame-rate dropped down. The lower the frame-rate, the more noticeable the ghosting. However, looking for a similar effect in the Tomb Raider demo proved fruitless - probably because high-frequency detail that took centre-stage to a similar degree wasn't in evidence, along with the fact that the frame-rate never drifted south of 48fps.

The remarkable reality is that Nvidia has finally consigned screen-tear and judder to the past - we approached the technology with all the scepticism in the world, but having seen it in action, it genuinely works. There are compromises, but the fact is that the choice presented to the gamer here is a no-brainer: while noticeable, the ghosting didn't unduly impact the experience and side-by-side with the juddering/tearing traditional set-up, the improvement was revelatory.

So that's the good news, but what's the bad? Well, if you own an AMD graphics card, you're in bad shape - G-Sync is a proprietary technology that remains Nvidia-exclusive in the short term, at least. There were indications that the tech will be licensed to competitors, but it's difficult to imagine that Nvidia won't want to capitalise on this in the short term. Secondly, you'll most likely require a new monitor.

In theory, existing monitors that are 144Hz-capable can be retrofitted with a new scaler board in order to gain G-Sync functionality - the Asus VG248QE has already been confirmed as the first monitor that will be upgradable. The question is to what extent display vendors will want to offer the replacement scaler module when their interests are probably better served by selling a new monitor. Only time will tell on that one.

"The good news is that G-Sync is an astonishing technology. The bad news is that you may need to replace your existing monitor, though upgrades will be available for limited models."

From there, the next reasonable question is to what extent higher-resolution monitors are invited to the party - we saw 1080p displays at Nvidia's event, but having moved onto 2560x1440 and recently sampled 4K, we really want to see the technology rolled out onto more pixel-rich displays. This is very likely to happen: sustaining that even, consistent performance on higher-resolution displays is a massive challenge, and G-Sync technology will prove even more advantageous there than it is with the 1080p displays we saw.

Beyond traditional desktop PC gaming, the applications elsewhere are mouthwatering. Laptop GPUs have far more issues producing smooth, consistent performance with the latest games than their desktop equivalents - a G-Synced gaming laptop will offer a palpably better experience. And the same thing goes for mobile too. After the main presentation, John Carmack was talking about the challenges of optimising for Android - that it proved impossible to get code he was running at 56fps to hit the magic 60 owing to SoC power management getting in the way. G-sync would resolve issues like this.

The arrival of the new technology is a genuine game-changer in many other ways - and at the event there was almost a sense of "what do we do now?" mild panic from the PC enthusiast press mixed in with the elation that we were looking at a genuine game-changer. In our recent Radeon HD 7990 review, we put the case that the reality of reviewing PC graphics cards had to move away from raw metrics and towards an appreciation of the gameplay experience, particularly in terms of consistency in update. As you can see from the screenshot below, we've been working on improving our performance tools to include a visual representation of judder. The arrival of G-Sync means that while the frame-rate metrics on the left won't change, the new consistency meter will be an entirely flat line on G-Sync systems judged by perceptual terms. Drops in performance won't be measured by the perception of the screen - far more by the variable lag in your controls.

"G-Sync matches GPU frame update timing with the refresh of the display, completely removing duplicate frames and providing an eerily smooth gameplay experience - even at 40fps."

Indeed, traditional bar-chart driven GPU reviews could almost become somewhat meaningless - even if an AMD card outperforms an Nvidia competitor by 10 or 15 per cent, if it doesn't have G-Sync, the problems with tearing and judder will still be there, but they won't be on what traditional metrics will tell you is the weaker card. By extension, we can also foresee that this will be a problem for Nvidia too - if the perceptual difference between, say, 45fps and 52fps, is ironed out to a great extent by G-Sync, we wonder if there will be enough differentiation in the product line-up to make the more expensive offering worth the additional premium. What is needed here is more testing on the impact of frame-rate differences on the gameplay experience - G-Sync may solve tearing and stuttering issues, but it can't address input lag, which does tend to be impacted by lower frame-rates (though this too can be addressed to a certain extent by developers).

Three weeks ago, we described AMD's Mantle API as a "potentially seismic" innovation in the PC space, offering console-level access to PC GPU hardware for increased performance. It's safe to say that as enticing as Mantle sounds, Nvidia has somehow managed to trump it, by offering a new technology that must surely become the new standard for PC displays in the fullness of time, instantly working across all games with no developer input required. When asked directly which was more important - Mantle or G-Sync - Epic's Tim Sweeney and John Carmack both instantly, unequivocally, gave the Nvidia tech the nod.

We hope to bring you a more complete test across a range of games soon. Everything we have seen to date suggests that G-Sync is the real deal - and the fact that luminaries with the calibre of Johan Andersson, Sweeney and Carmack so enthusiastically evangelised the tech speaks for itself - but it's clear that there's a vast amount of testing to do with the technology and a raft of questions to answer, both specific to G-Sync tech and also to the wider industry. Specifically: is there a threshold at which the g-sync illusion starts to break down (35fps seemed to be mentioned after the event)? What is the perceptual difference - if any - offered by running, say, a GTX 760 and a GTX 770 at the same quality settings? Will we see competing technologies from AMD and will we see fragmentation in the PC market, or will Nvidia exercise the power of the patents it has in place?

"G-Sync marries graphics and display technologies together to a degree that has never been seen before, eliminating the most ugly artifacts from the gaming experience."

We're also curious if next-gen console could conceivably be invited to the party at some point. Our guess is that it's simply not possible in the short term owing to a combination of no G-Sync support in living room displays and no appetite from Nvidia to accommodate the new games machines anyway. Across the medium to long term, the situation still looks bleak - Sony could introduce similar technology that works between PS4 and Bravia displays, but adoption needs to be widespread to really make a difference.

It's been an interesting couple of days at Nvidia's media briefing. With the arrival of Xbox and PlayStation replacements based on PC architecture, there's the sense that the graphics vendors are looking for the ways and means to more effectively differentiate themselves from the consoles. Increasing GPU power year-on-year helps, of course, but the consoles have always punched above their weight from a visual perspective. 4K support is welcome (higher-end textures for 4K displays still means higher-end textures for 2.5K and 1080p displays too), but we're still looking at more challenges there - specifically that the GPU power to run 4K on a single card simply isn't there yet, and display prices are currently astronomical.

AMD's response is to embrace console and work its optimisations into PC gaming, while offering developers superior audio solutions. Nvidia's response is altogether more striking: G-Sync marries graphics and display technologies together to a degree that has never been seen before, completely eliminating the most ugly artifacts from the gaming experience. Tearing and judder are finally a thing of the past - and after years of putting up with it, it's about time.

This article was based on a trip to Nvidia's press briefing in Montreal. Nvidia paid for travel and accommodation.