Eurogamer Editors' Games of the Decade

Six of our Top Men (and a lady) pick a game they love and explain.

Who wants one present on their birthday when they can have loads? Not us, certainly, which is why in addition to Eurogamer's Lifetime Top Ten, we're also publishing this series of blogs from Eurogamer editors past and present, each of whom got to pick a game of the last 10 years that meant a lot to them and explain why.

- John Bye (Editor, 1999-2002/3) - Unreal Tournament

- Rob Fahey (Long-time contributor / founder of GamesIndustry.biz) - Deus Ex

- Ellie Gibson (News Editor, 2005-2006 / Content Editor, 2007-2008 / Deputy Editor, 2008-present) - Fruit Mystery

- Kristan Reed (Editor, 2002-2008) - Half-Life 2

- Johnny Minkley (Eurogamer TV Editor, 2006-present) - Guitar Hero

- Oli Welsh (Long-time contributor / MMO Editor, 2008-present) - World of Warcraft

- Tom Bramwell (Editor, 2008-present) - ICO

John Bye (Launch Editor) - Unreal Tournament

When Eurogamer launched in 1999 I was a dyed-in-the-wool id kid.

As a teenager I discovered the joys of multiplayer gaming by fragging my friends in Doom deathmatch sessions over the school network. At university I joined the online gaming community, downloading literally hundreds of homebrew Doom maps from the legendary Walnut Creek file depot at ftp.cdrom.com, along with a level-editing tool that gave me my first real taste of game development.

As time went by I spent more and more time creating and reviewing Doom maps, and less time going to lectures. Eventually I dropped out of university entirely and founded my own online games company, The Coven, recruiting some of my favourite designers from the mod community to make expansion packs for the Quake games. I even spent a year running the world's biggest Quake fan site, PlanetQuake. And it was while covering a Quake II tournament for PlanetQuake that I first met the Loman brothers. A few months later they invited me to join their new company as Editor-in-Chief of Eurogamer.

So why am I writing about Unreal Tournament as one of my favourite games of the last decade?

10 years ago, nobody in their right mind would have bet on Unreal Tournament. Announced just a couple of months after Quake III Arena was first revealed to the world, it was written off by a lot of people as a cheap, bandwagon-jumping knock-off. One of Epic's own designers described Unreal Tournament to me as "a bad joke". It's not hard to see why.

id Software was a pioneer of online gaming, from the fast-paced modem-to-modem action of Doom through to the internet deathmatch perfection of QuakeWorld and the addictive grapple-happy teamplay of Quake II CTF.

By comparison, Epic's first foray into deathmatch was a disaster. Unreal was a fantastic single-player game for its day, but its multiplayer was a lag-ridden mess that was barely playable out of the box. Facing a chorus of complaints from fans, Epic had to release a steady stream of patches to finally bring the game's network code up to par with the Quake series.

And yet, against all the odds, Epic stole id's thunder.

My own first taste of Unreal Tournament came just a couple of days after Eurogamer's launch at ECTS 1999. Having failed to blag my way into SEGA's hot-ticket Dreamcast party, I instead found myself in a cellar bar in north London with Epic boss Mark Rein, programmer Brandon "Greenmarine" Reinhart and a host of outcasts... I mean, PC gaming journalists.

Things got off to a good start when the rest of the press decamped to another server mid-game, leaving me playing with a group of AI bots for a quarter of an hour until one of our hosts politely pointed out to me that I was the only human left in the game. While their limited range of taunts might not get them through a Turing test, the bots' deathmatch behaviour had been almost flawlessly believable.

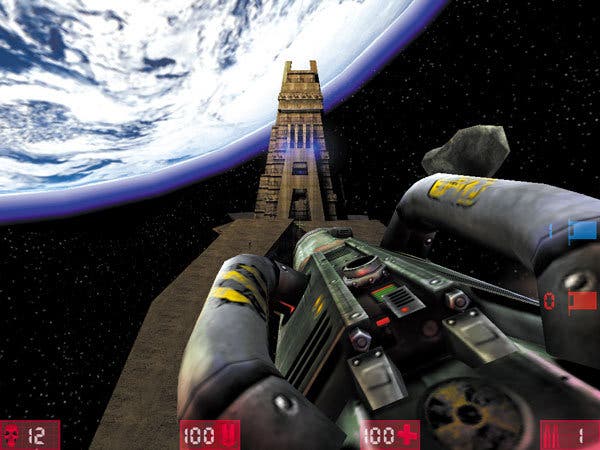

A short stint storming the beaches in Assault mode and a quick dip in the steady shower of blood that is DM Morpheus with the instagib mutator enabled showed the game's versatility, but it was the epic CTF battles on Facing Worlds that proved the biggest draw of the night.

Perched precariously on a ledge high up on the side of a tower, watching the other players scurrying around ant-like on the rocky asteroid far below as space tumbled around us, it was hard not to be blown away. Not least because I had my trusty sniper rifle to hand, my headphones echoing with the words "headshot" and "killing spree", only drowned out by Greenmarine screaming "where's that sniping bitch Gestalt" from the other end of the bar as I turned his head into a fine red mist for the umpteenth time and shifted to another shadowy balcony.

So it was perhaps no great surprise when, a few weeks later, Unreal Tournament scored Eurogamer's first ever perfect 10/10 score.

As a games journalist working on what was then a small independent website whose editorial department was essentially run out of my spare bedroom, I didn't have a lot of time to play games just for fun. It was a 24 hour, 7 day a week job. Most days I was playing games we had been sent for review or preview, typing up or editing the latest news reports and articles, or taking the train in and out of London for press events.

Unreal Tournament is one of the few games in the early days of Eurogamer that I kept going back to months after I'd finished reviewing it, a game that I played to unwind after a long day playing other games. Whether it was trying to break the one-minute barrier in the speed running mayhem of Assault mode, battling back and forth amongst the alleyways of Domination, or dropping shrapnel shells at people's feet with the wonderfully chunky flak cannon in a fast and furious free-for-all deathmatch, Unreal Tournament was an endless source of entertainment.