Retrospective: Fahrenheit

Winter wonderland or snowballs?

Here's my impression of David Cage brainstorming ideas before making a game:

"Okay, it shall be set in a regular city, slightly in the future. Our character must get through his day, while becoming embroiled in a strange mystery. A peculiar girl is stuck in a tornado, and the player must rescue her before all the water in the world turns to stone. Aliens attack. At the end it rains cars."

While Heavy Rain stayed in reality, Omikron and Fahrenheit begin with a facsimile of a recognisable life, and then dive headfirst into a swimming pool of insane.

Technically I've replayed Indigo Prophecy rather than Fahrenheit, since that's the version on Steam. It's the strangely censored version of the European cut, sex scenes removed, nipples erased, and, most amusingly, bikinis worn in the shower. But otherwise it's identical, the tale of Lucas Kane attempting to recover from committing a murder against his own will.

It's a stunning start. After Cage's hilarious tutorial, in which he appears as an animated version of himself and explains the game's lunatic controls, you watch a scene in which Lucas stabs a man to death in a diner bathroom.

The scene is brilliantly put together, rapid near-subliminal shots of key clues flickering as Lucas staggers like a poorly operated marionette. A cloaked figure surrounded by candles, a crow, a small child, all invading a grisly murder. Then when the victim is dead, stabbed through the heart, we take control of Lucas as he appears to wake up. We've done a bad murder.

Here you can choose how to act. It's possible to burst out of the bathroom door, covered in blood, and crash through the emergency exit of the diner in the most attention-grabbing way imaginable. Or you could choose to wash your arms (you're bleeding yourself, having involuntarily carved markings into your forearms), and calmly return to your table, pay the bill and leave.

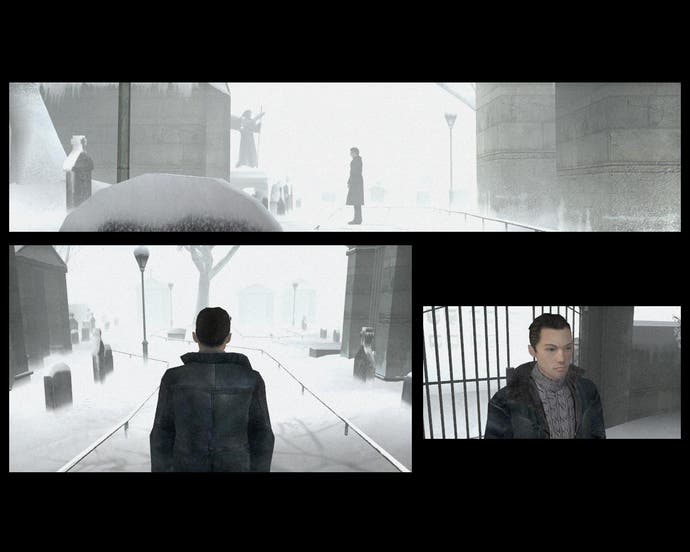

Better still would be to make some attempt to hide your crime. However, there's a cop in the diner, so there's not too much time. Here you can hide the murder weapon, drag the body into a toilet cubical, mop blood from the floor. It's up to you. However, here the first use of the game's brilliant split-screen appears, as you see the cop plodding towards the bathroom door.

The body is discovered at some point, and an absolutely intriguing opening becomes even more fascinating when the next scene has you playing as the two homicide cops called to investigate.

Should you have hidden the knife, the cops will have to hunt for it to get important fingerprints. If you moved the body, mopped the blood, then the cops can figure this out too. As Carla and Tyler you speak to witnesses, gather clues, and begin your pursuit of the killer.

When the game first came out in 2005, such an opening created incredible expectations. This was utterly extraordinary - you were playing against yourself. You were hunting for yourself, hiding from yourself, seeing both sides of a cat-and-mouse pursuit. What a remarkable idea for a game. It would have been.

It's interesting returning to it, knowing that not only will this back-and-forth only play a small part throughout, but that it was to be a constant descent into lunacy. The thrill was still there. The opening is still such a great idea, and it's still a treat to play it.

But this is less a game than a collection of ideas for other games to borrow. Or ignore. It's as if Cage looked at gaming, across many genres - adventure, first-person shooter, third-person action, rhythm-response, RPG - and attempted to abandon all traditions. The result is a hodgepodge of brilliance and idiocy, inspired reinvention and downright awful ideas.

Playing two cops, each has different skills. Carla's a much better police officer than Tyler, but Tyler will spot a detail or have an idea Carla may miss. You use them differently, but they work as a team. Heck, playing multiple characters is still a novelty, let alone conflicting characters. Here you play Lucas, his brother Markus, Carla, and Tyler. And perhaps most significantly, you're not only sympathetic to the murderer but playing as him, attempting to get away with the crime.