Gaikai

Dave Perry sells you into blissful slavery.

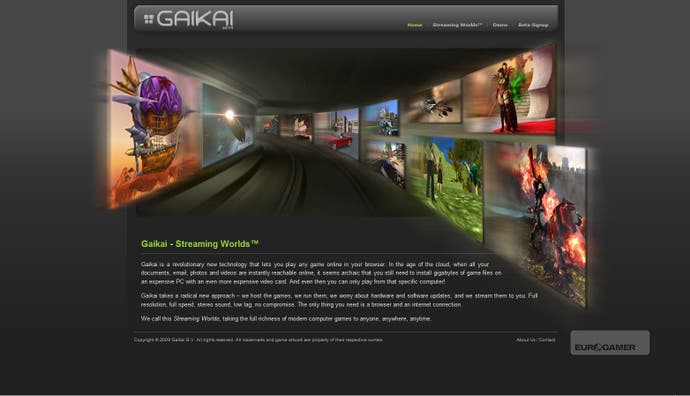

We all know what Gaikai is by now, and if not, there's the official website to loosely explain the concept: play games in your web-browser, even if your PC or Mac would be unable to run them for technical or licensing reasons. There's also that widely-viewed demonstration video of Gaikai co-founder and chief evangelist David Perry using it on his PC and commentating over the top.

We also know that, unlike OnLive, Eurogamer's resident mad scientist and Digital Foundry blog editor Richard Leadbetter believes it will actually work. It's not making outlandish promises about 720p at 60 frames per second, it's saying that with a bit of window-resizing, a variable frame-rate and clever programming, you can have a solid experience that most people would accept - especially the people Gaikai most cares about, the idling PC and Mac users who currently play millions of rubbish Flash games at lunchtime and while the dinner's in the oven.

But there are still plenty of questions. What do publishers actually do? How does Gaikai avoid server congestion? There's also the question of what form the consumer experience actually takes. It's not a portal website that lets you pick games to play - the demonstration site used in Perry's video walkthrough was for testing only. Nor is it a subscription service. There's been talk of it appearing on game publishers' websites, or at retail locations, and even on sites like Eurogamer. But if you dig down into Perry's comments, there's nothing concrete, just hypotheticals.

The reason there's a lot of confusing chatter about the Gaikai end-user experience is pretty easy to diagnose: Gaikai isn't sold to you; it's sold to the Activisions and EAs of the world. But what are they buying?

"So, selling to them is to sell new gamers," Perry tells Eurogamer after his Develop Conference speech last month. Perry believes that the number of gamers clicking to play using Gaikai and then actually following through on that and playing will be significantly higher than on existing game portals and download services, which often lose potential customers to technical problems or boredom - games not launching, games taking too long to launch, and so on. "If I told [the publisher] for every gamer, it's currently costing you $5, and I can get them for $1, and it's like a fraction of what you're currently paying, then it becomes commercially viable and makes sense to a publisher, and I don't have to explain any more."

So how does it work from a publisher's perspective? "They put the game on the service. They come to a dashboard, they create an account, and they add their game to the service. So if you wanted to publish a game tomorrow, you could do that. You come on, you register, you add the game to the service - it will have to be tested of course to make sure it's not breaking any rules - but as long as it's not breaking any rules you can drive people to your games." The way publishers use it is analogous to iTunes, he says. "Apple doesn't go, 'Please can we have your games?' They just make the service and if you use it, great, if you don't, that's fine." Just remember: the way you use it will be very different.

That's also the reason Perry is constantly correcting people who liken Gaikai to OnLive. They have some common technological genes - or at least philosophies - but their commodities are considerably different. OnLive is closer to something like Steam, with a different delivery mechanism and attendant cost concerns, whereas Gaikai is more like an embeddable YouTube window showing licensed content with a range of possible access levels determined by the licensor. In other words, publishers use Gaikai to expose you to their wares, but how they do that is up to them. Nintendo might embed a trial version of Mario Kart on Eurogamer as part of a marketing campaign, for example, or Blizzard might let you play full-blown World of Warcraft on its website. And by selling volumes of gamers to publishers, Gaikai is in a strong position to react to demand rather than having to anticipate, say, one million people turning up at midnight to play Grand Theft Auto V.