Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory

Even your mum could play it. In theory.

There's a running joke/truism in the music scene that most bands suffer from the 'difficult' third album syndrome. It's not exactly a hard and fast rule (as there are some notable contradictions), but it's usually the point when previously unassailable success starts to unravel and the cracks start to show. Call it overconfidence, lack of inspiration, the well of creativity running dry, or just trying to play to the crowd, but Chaos Theory is Splinter Cell's Be Here Now.

Three steps forward, four steps back, "Choas Theory" (that's honestly how Ubisoft has spelled it on the spine of our promo copy) is the frustrating tale of a project that's added so much good stuff to a winning formula, but walked silently away from addressing some of the real issues that have dogged the series right from the beginning, while also introducing some new features that either add very little or actually detract from what made the game so compelling in the first place. Has Ubisoft genuinely disappointed, or are these the words of someone who expected too much? That's for you to decide.

The real follow up

But first a refresher. Chaos Theory is the 'true' sequel to the original 2002 stealth romp, or in other words it's the second Ubisoft Montreal Splinter Cell game - last year's Pandora Tomorrow being largely considered something of a filler release knocked up at Ubi's Shanghai studio to make the most of the commercial fervour surrounding the debut classic. On that basis, this interesting, almost unique state of affairs put Pandora Tomorrow into context. It was creatively no more than an expansion pack in single player terms, being little more than a set of new levels and scenarios to service the fans, while also justifying its full price tag with a rip roaring online multiplayer mode that was widely acknowledged as one of the true innovations in multiplayer gaming of recent years.

With all this in mind, the stage was set for Chaos Theory to really advance on what had gone before; improve on the storytelling, provide a more rounded, more inclusive gameplay experience (i.e. one that didn't kill the player off every 30 seconds or checkpoint your progress with a sliver of health left), crank up the already grand visual opulence, throw in a few new cool Third Echelon gadgets and give the ageing Clooney wannabe the chance to show us his new rubber perv suit and the new moves he's been learning down at the self defence class since last time out.

Unlike SC's closest competitor Metal Gear Solid, the storyline's never been the game's strong point. While MGS mastermind Hideo Kojima might harbour delusions of grandeur in that department and go too far in wanting to make grand sweeping movies with Harry Gregson-Williams soundtracks alongside his games, at least he's trying to push things forward. Ubisoft Montreal is still floundering very much in the malaise of old school videogame pre-mission thinking. It's evidently trying manfully to create a convincing, focused game world with characters the player cares about, but it's still not working. Content to continue with the formula of stitching together fast-paced news footage, quickfire biogs on generic arch crims and knockabout banter between Sam and his Third Echelon employers, Chaos Theory still fails to truly engage the player in setting the scene, or giving you a clear definition of your goals or why you're chasing so and so, and what his role in the crime caper is. It's easy to lose the thread of what's going on, and while that may be at least partly to do with a failing attention span, it's a problem Ubi still hasn't addressed beyond retaining its high quality voice cast and doing an admirable lip-synching job on its main characters. Following up its cut-scenes with static text descriptions of what's going on feels plain lazy these days.

Splinter Sell or Splinter Smell?

Where Chaos Theory gets things right in terms of scene-setting is the actual in-game banter, which - tedious quipping about Sam's increasingly mature years aside - really help give you a sense of place, as well as regular reminders of why you're doing what you're doing. It's a game that really needs it too, as most of your time with Chaos Theory will simply be a matter of engaging with easy-to-pick-off generic goons that patrol in near darkness in easy-to-manage ones and twos.

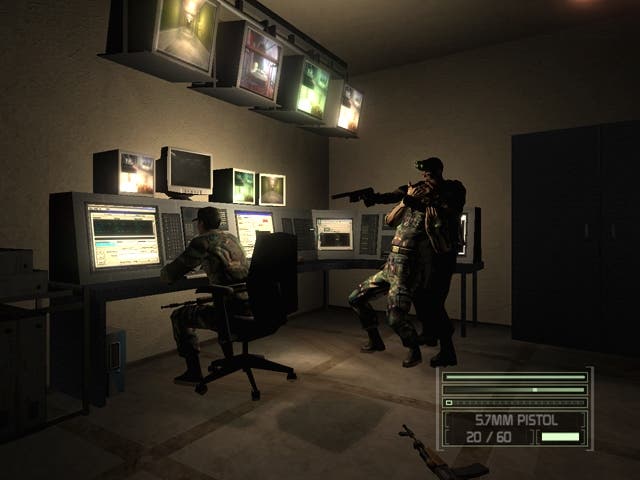

A typical sortie in Chaos Theory's ten levels goes roughly like this: insertion in some random dark place of great beauty and great danger, turn on night vision in order to see anything (being sure to shoot out any lightbulbs you come across), crouch and sneak up slowly behind stationary or slow moving guard, grab him, interrogate, incapacitate, save game.

Or, if you can't be bothered with the slow and sure process of sneaking up behind people the newly enhanced close combat manoeuvres make the job of taking out guards easier than ever. Too easy, in fact. Anyone familiar with previous Sam Fisher adventures will probably be aghast at how straightforward the whole procession is; especially with a 'quicksave anywhere' facility replacing the far more challenging and sensible checkpoint system. Kill, save. Kill, save. Kill, save. And so on.

More forgiving than Jesus

There's forgiving, and then there's just ridiculous. It was obvious some of the more frustrating elements and difficulty spikes had to be smoothed out to give people more incentive to carry on, but now everything's such a formality (the new knife attacks a prime example of making things too easy) it's hard to really care. If you mess up, you just quick load and carry on and all that rich tension of old just melts away.

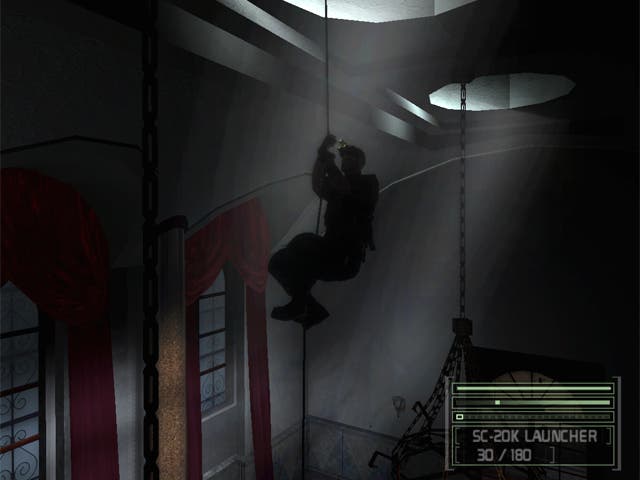

Even if you happen to alert a guard while they're busily unloading their clip into your face, Mr Fisher has the incredible ability to knock out literally any game enemy with one swift blow no matter what anyone else is doing to him at the time. Amazing. While Ubi has gone to great lengths to introduce some exceptionally cool new moves that enable Sam, for example, to dangle off ledges and yank enemies to their doom (off the top of the Light House - genius), or hang from pipes and perform an inverted neck break on enemies unfortunate enough to wander underneath him, you either rarely get the chance to pull such things off, or you settle into the rapid realisation that, actually, it's far easier and more effective to knee your foe in the bollocks or slap your extended palm under their chin. After all, as gamers we generally take the most effective option when presented, right?

As such, your guns are more of a hindrance than a help at times, often alerting swathes of guards to your presence and resulting in a very quick death indeed. In fact, while we're on the subject, you'll be regularly gob-smacked at just how quickly enemies react to your creeping presence - one second engaged in any number of tasks from urinating to fixing locks, and the next millisecond unloading their gun with military precision - yet when patrolling a dark area they rarely have the presence of mind to light up the scene.

I believe in a thing called lightbulbs

It's probably at this latter point where you find yourself tiring of the whole darkness mechanic. It was a huge step forward in the first Splinter Cell, and creeping around in the dark playing hide and seek was a real buzz, but now the whole game relies on it to such an extent that it's laughable. Even the most mundane scenarios and locations are so dark and so obviously contrived around the central game mechanic that it ceases to be believable anymore. Factor in odd game design decisions that have now abandoned key Splinter Cell principles like not leaving any bodies lying around and not triggering more than three alarms and it's a game that - while more accessible - is dumbed down to the point of disinterest. Once you realise there's no punishment for leaving dead bodies where you killed them or any real incentive to avoid setting off alarms you stop playing the game with the same degree of skill that you once did. It leaves you with a lack of achievement, a lack of challenge and as such feels very much inferior to previous games in the series. Apart from the fairly challenging bomb defusal section on the standout penultimate Bathhouse level, the game's just a fairly tired romp mainly involving taking out dozens of dumb guards, hacking doors, checking every computer under the sun and so on until you're done.

And yet there are plenty of positive things to admire about the game everywhere you look; things which have rightly been trumpeted to get people excited about the game in the run up to launch. On a visual level it's impossible not to admire the superb animation that really makes Fisher one of the most satisfying game characters to control that there has ever been. In terms of the sheer control responsiveness and range of movements it's just spot on and a lesson to anyone hoping to make an action game (particular thumbs up to the new aim-switching ability that now lets you choose whether to aim over one shoulder or the other).

Fisher is one of the only game characters who looks like he's physically interacting with the environment, rather than having just been plonked into it, so huge kudos there. Okay, so maybe the character models still have an overly plastic look about them still, but the movement and level of realistic motion capture is a sight to behold and something that Ubi has over most of its competitors. Again, the actual game engine is streets ahead of most of the current crop of action adventures, with the PC version in particular capable of some outstanding texture detail, beautiful lighting and particle effects; it's just a shame that most of the time it's too dark to show it off in its full glory.

Enjoy your stay

As a whole, it's certainly a game world you'll really enjoy occupying (although what's with the Airwaves ads for gawd's sake?). The environments really drip with atmosphere at times, with some occasionally inspired soundtrack dramatics designed to give you the fear blasting into action. The diverting paths also help give the gamer a degree of choice, which is always good to see, but it's arguably undercooked in that respect, with some hilariously contrived crawl spaces inserted in the unlikeliest of places - just to give the player a supposedly 'sneaky' shortcut, when it would have been more useful and convincing to design levels more around Fisher's athletic abilities. All too rarely does the player really get the chance to use their full repertoire of impressive moves - the split jump, the pipe hanging, the rappelling and so on - and all too often we're left crawling through stupid air ducts instead that simply wouldn't exist in real life. Is it us or do these things only seem to exist in the minds of movie and games designers? It's probably become the biggest gaming cliché of all.

Another undercooked element of the 'new' Splinter Cell is its more 'mature' content, which seems to consist of Sam being able to hold a knife to the throat of his enemies, but never have the ability to go the whole hog and use it in this situation. You can, of course, slash your foes and stab them in the gut when not using your guns but but nevertheless we wanted Fisher to be meaner, more aggressive, and give the enemy a real taste of their own medicine. Ultimately he's just too damned nice most of the time.

So what of the celebrated multiplayer? For some players it might even be the main event, especially in the light of the newly implemented co-op mode; but like nearly all multiplayer experiences it's one that depends as much on how good your assistants are as the game itself. Set over four levels, the co-op mode essentially sticks to the same principles as the main single-player campaign, but designs the level in such a way that you can work together to use moves that enable you to get into areas you otherwise wouldn't be able to on your own. The most obviously useful one is the Boost, which allows you to boost your team-mate up to a ledge or pipe. Others such as the Human Ladder let a player hanging on a ledge act as mean to climb up, while the Long Jump is an odd but cool one that lets you throw your team mate towards a target, such as an NPC and knock them out in the process.

Hungover?

Other contextual moves such as co-op Dual Rappelling and standing on a team-mate's shoulders are pretty useful when the occasion arises, but probably the best of all is the Hang Over, which has one player controlling a rope while the other has the opportunity to be dangled over an NPC to perform the deadly inverted neck break.

But as cool as all this sounds, the reality of co-op is two of you wandering around looking for the next place to go, and if you lose each other it can be a faff trying to co-ordinate each others plans ("I'm over by the vent" "Which one? Where?"), especially given the absence of a map to gauge where they are. Given that it's something of an added extra tacked onto the main event, it's hardly surprising to note that out of the four levels, only one of them can be considered a worthy addition. In the main these levels feel quite empty and after a while you'll quickly want to move back onto the main versus multiplayer mode.

If you're one of the many that enjoyed what Pandora Tomorrow's maps had to offer then you'll be right at home here, with the same maps returning here in addition to some new ones. Once again it's two on two action; two spies (the Sam Fishers, effectively) against two Mercenaries, with the latter playing from a first-person perspective, being slower paced and having machine guns and torches, but minus the athletic stealth abilities of the spies. If you haven't tried it, it's one of the most brilliantly balanced multiplayer experiences around, albeit one that you can only really start to enjoy once you get to know each of the vast, sprawling maps intimately and know their weaknesses. Until then, you'll probably get a bit annoyed with how rubbish you are at it.

A distraction from the main event

The main thing to note is how Chaos Theory has basically moulded the various multiplayer strands of old into a more coherent story mode. In other words, different objectives are tied together in a sequential list of tasks to be performed; so, for example, you might need to steal/protect a hard drive from a server, set or defuse a demolition charge on a server or neutralise/protect a particular terminal. It's not really a 'story' as such, but it just mixes things up a bit more and means you're doing more than simply the one task. On top of that there's the standard deathmatch between the Shadownet Spies and the Argus PMC, or a Disc Hunt mode, which if you hadn't guessed already is CTF in Fisher's world, so all in all, lots to do, plenty of value all round and doubtlessly hours of entertainment for those of you who enjoy your online gaming - but be aware that as many people that love SC's multiplayer, there are an equal number of braying types that don't get on with it.

A small word of caution, though. We're slightly baffled why (on the PC version at least) Ubi couldn't be bothered to keep the key-mapping consistent between the single and multiplayer modes. How hard can it be? Also, don't expect the visual quality of the single-player mode to appear in multiplayer - it's two entirely different teams responsible for both, and as such the engine appears to be a few years behind for some inexplicable reason.

Once you factor all of these distinct strands of the package together there's definitely a lot to commend and a lot of enjoyment to be had. But our overriding concern is for the main event, the single-player mode. This is arguably what most people buy Splinter Cell games for, and it seems that in attempting to take the series forward Ubi has neutered the experience to pacify those lacking the patience to play it the way it had to be played in the early days. As such, the bottom line for us is that it has morphed into a dumbed-down experience that is no longer anywhere near as gripping and compelling as it once was, and while the multiplayer does bail out the overall value of the package to a large extent, it can't mask the decline elsewhere. We reckon we could probably see the point of what Ubisoft was trying to achieve with Chaos Theory, but we'd need night vision goggles for that. Maybe next time the series can go back to its roots and keep the long-term fans happy as well, eh? It's still an eight, but only just.