The Super Mario Bros. Story

From the archive: a series retrospective.

Every Sunday we haul an exciting article out of the Eurogamer archive so you can read it again or enjoy it for the first time if you missed it. Oli's look back at the Super Mario Bros. games was originally published on 15th November 2009.

"If he finds a warp, he can jump worlds!"

In the climactic scene of the 1989 film The Wizard, a withdrawn kid called Jimmy who's a preternaturally gifted videogame player is competing at a tournament. In the final, he has to play a game he's never played before: Super Mario Bros. 3, then unreleased in the US. For over five minutes of screen time, footage of the game looms large over a screaming audience while Jimmy's brother - suddenly possessed by the spirit of the back of the box - shouts tips and game features from the sidelines.

It's a silly scene in a bad, exploitative movie. It's full of implausibilities, it's badly acted and it's an embarrassingly naked advertisement for Nintendo. But it's also humbling. 20 years ago, the money shot in a major feature film was footage of a game. The game was presented accurately and honestly, discussed in gamers' terms, and the sight of it caused waves of excitement in the audience.

It may have been kids' stuff, but the launch of Super Mario Bros. 3 was also a major cultural event attended by none of the posturing, misunderstanding and self-conscious debate that has recently swirled around the releases of Grand Theft Auto IV or Modern Warfare 2. That's real acceptance. It was what it was, and of course you loved it, how couldn't you? It was Mario.

All this happened just four years after Nintendo had re-invented the home videogame with Super Mario Bros. How on earth did we get there so fast? And where's the warp that gets us back?

Minus World

You know the prehistory: in the beginning was the jump, and the jump was the man.

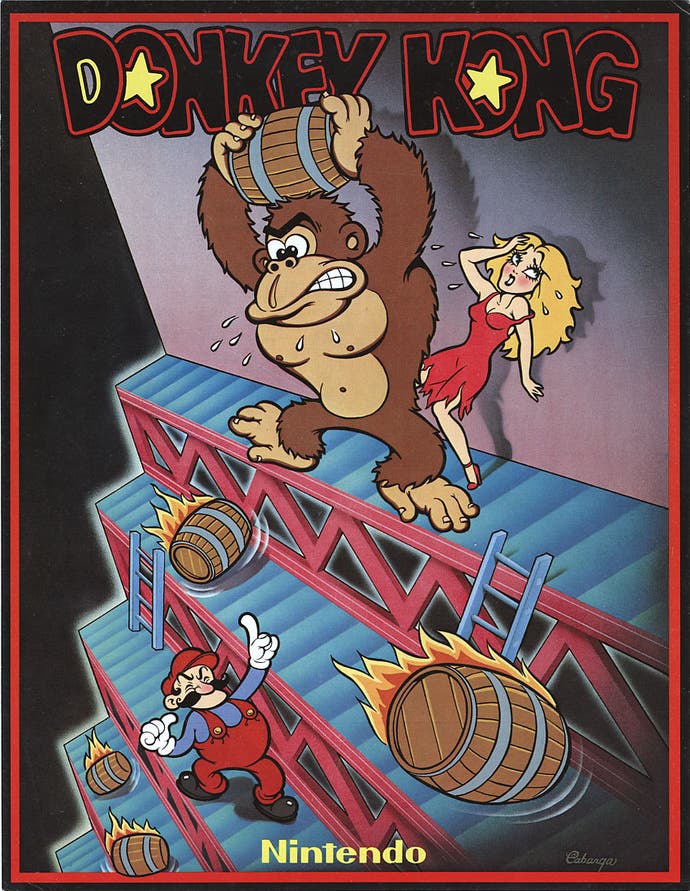

Jumpman was the fat, comical carpenter in the Nintendo arcade game Donkey Kong. He was called Jumpman because he jumped, and he jumped because that was all there was to do. He wore dungarees so you could see his arms move, a hat because hair was hard to draw in pixels, a moustache to emphasise his large nose. "Noses say a great deal," said his creator, Shigeru Miyamoto.

In his next arcade game, Jumpman acquired a proper name (Mario), a new profession (plumbing), and a brother to enable two-player gaming (Luigi). He didn't acquire any new accessories or abilities, though; he still just jumped. In Mario Bros., he battled a strange menagerie of creatures in the sewers of New York. Barring Donkey Kong retreads, it was the last time Mario would be seen in a setting that was remotely appropriate to him. But that was the point.

World 1-1

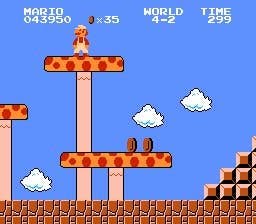

When Mario came up out of the sewers, it was into a strange new world. You could tell it was mysterious because it was plastered with question marks. The question marks were on boxes, and you never knew quite what would come out of those boxes when you hit them.

There were mushrooms in this world that made Mario grow in size, not to be confused with the mushrooms which were people, all called Toad. There were turtles with wings. There were conventional fantasies too, castles and a princess to be saved. Only the clouds looked like they were from the real world (and that wouldn't last). It was like a dream.

This was Super Mario Bros., released in 1985 for Nintendo's first home console, the Nintendo Entertainment System. Miyamoto's dumpy, goofy everyman was still jumping, but now he was running, too, really going for it, courtesy of a dash button. He could achieve amazing speeds and jump to ridiculous heights, and the player was given an exquisite level of control over him, varying the height and length of the jump, guiding his course in mid-air, feeling his giddy momentum. It was beautiful and exhilarating. In the dreamworld, out of place, the ordinary little man became a graceful superbeing.

"What if you walk along and everything that you see is more than what you see - the person in the T-shirt and slacks is a warrior, the space that appears empty is a secret door to an alternate world?"

Shuigeru Miyamoto

And the dreamworld was so much bigger. Not only were there dozens of levels, but the levels scrolled along for screen after screen. (Always from left to right, though; in Super Mario Bros., you could never go back. Is that because it wasn't possible with the technology, or just because it hadn't occurred to Nintendo that you would want to?) This was amazing, but it wasn't the half of it.

Halfway through the first level, Mario could descend through a pipe - it wasn't marked, you had to find out through trial and error which one - to find a secret cave filled with coins. The second level was all cave, and there Mario could smash through the ceiling and run off the top of the screen. No sooner had he landed in a vast new world than the plucky plumber was finding out what was underneath it, what was behind the scenes. Secrets were everywhere, and everything was more than it seemed.