See how Valve predicted the future of PC gaming in 2008

From the archive: Newell and company's vision seemed dramatic at the time.

In June 2008, Valve invited journalists to its offices to talk about the future of PC gaming and we published this article recounting the experience. Looking back six years later, it's fascinating to think how dramatic each prediction felt at the time and yet how so many of them turned out to be conservative. Facts and figures are obviously out of date, but otherwise it's still a great insight into how Valve thinks - and what it thinks about.

When Valve summoned a handful of US and UK journalists to its Seattle headquarters at the end of last month, it promised to talk about the future of Steam, its digital distribution system. That it did, revealing the ambitious Steam Cloud service for remote storage of game data, and boasting that it would soon be making more money selling games digitally, all the while remaining untroubled by piracy.

Valve mastermind Gabe Newell and his cohorts had an ulterior motive for bringing reporters together, however, and unusually for an ulterior motive, it wasn't a wholly self-interested one. It was this: to evangelise the PC as the games platform of the future.

"This really should be done by a company like Intel or Microsoft, somebody who's a lot more central to the PC," says Newell, pointing out that companies like Blizzard, PopCap and GameTap would have just as much to say as Valve about how PC gaming is leading innovation in technology, business models, and community-building. But, notwithstanding Microsoft's occasional promotion of Games For Windows - an initiative Newell refrains from attacking directly, but exudes disdain for - that support has not been forthcoming.

Where console platforms have merciless and well-funded PR armies poised to combat any criticism, negative stories about the PC - mostly publishers, or developers like Crytek, complaining of rampant piracy and flat sales - run unimpeded. Sales data that focuses solely on boxed copies sold at retail appear to back them up. Valve has had enough. "There's a perception problem," says Newell. "The stories that are getting written are not reflecting what is really going on."

You want figures? There are 260 million online PC gamers, a market that dwarfs the install base of any console platform, online or offline. Each year, 255 million new PCs are made; not all of them for gaming, it's true, but Newell argues that the enormous capital investment and economies of scale involved in this huge market ensure that PCs remain at the cutting edge of hardware development, and consoles their "stepchildren", in connectivity and graphics technology especially. Meanwhile, Valve's business development guru, Jason Holtman, notes that without the pressure of cyclical hardware cycles, PC gaming projects - he points to Steam as an example - can grow organically, over long periods of time, and with no ceiling whatsoever to their potential audiences.

"If you look into the future, there's an important transition that's about to happen, and it's going to happen on the PC first."

Gabe Newell

More pertinent, perhaps, are the figures directly relating to games revenue that the retail charts - admittedly a stale procession of Sims expansions and under-performing console ports - don't pick up. "If you look into the future, there's an important transition that's about to happen, and it's going to happen on the PC first," says Newell.

At its heart, he explains, is a shift from viewing games as a physical product, to viewing them as a service - something that is also happening in other entertainment media. Digital distribution is part of that; more fluid and varied forms of game development, with games that change and engage their communities of players over time, are another; as is, naturally, the persistence and subscription (or otherwise) revenues of MMO games. None of this is reflected in the sales charts analysts, executives - and gamers - obsess over.

Valve sees 200 per cent growth in these alternative channels - not just Steam, but including the likes of cyber-cafes as well - versus less than 10 per cent in bricks-and-mortar shop sales. Steam has a 15 million-strong player-base with 1.25 million peak concurrent users, and 191 per cent annual growth; none too far off a console platform in itself. The PC casual games market, driven by the likes of PopCap, has gone from next to nothing to USD 1.5 billion dollar industry in under ten years, and has doubled in size in just three. Perhaps most surprisingly, Valve has found that digital distribution doesn't cannibalise retail sales - in fact, a free Day of Defeat weekend on Steam created more new retail sales than online ones.

And then there is the game that many claim has been the death of PC gaming, but that Valve sees as its greatest success story, and its future. "Until recently, the fact that World of Warcraft was generating 120 million dollars in gross revenue on a monthly basis was completely off the books," Newell says. "Essentially, [Blizzard is] creating a new Iron Man every month, in terms of the gross revenue they're generating as a studio. Any movie studio would be shouting about that from the rooftops. But it was essentially invisible."

Newell thinks that WOW is "arguably the most valuable entertainment franchise in any media right now", and also believes, rightly, that it could only ever have happened on the PC. He also tips his hat to South Korea's Nexxon for its enormous success with free-to-play, microtransaction-driven games like Kart Rider and Maple Story, soon to be aped by EA's Battlefield Heroes.

There is another reason for the gulf between the perception and the reality of the games market, Valve thinks, and it's a geographical and linguistic one. The dominance of the English language gives the US and UK games markets, where the PC is weakest, undue prominence. In several major Western markets - notably Germany and the Nordic countries - the PC performs much better. What's more, in the emerging markets of China, Korea and Russia, where gaming is seeing unprecedented, explosive growth, console install bases are negligible, and the PC is king. Valve thinks that there's a silent majority of global gamers who are skipping the console era entirely, the way these developing nations already skipped dial-up internet.

Steam is available in 21 languages for this reason, and Valve reckons that its speedy localisation and lack of physical distribution is an effective counter to the piracy common in these markets. It's also allowing Valve to get games to players in regions traditional channels don't support. "PC's are everywhere in the world," says Holtman simply. "PC's are the same all over the world. All of sudden, if you can open up emerging markets and go somewhere like Russia or South East Asia, you've gone way further than you can go with a closed console. There are 17 million PC gaming customers in Russia alone."

A key shift in this brave new world of games as services rather than products - and one that runs contrary to the traditional image of PC gaming - is a move away from graphical fidelity being the yardstick of progress. "As a company that's really proud of the job we do with graphics it's funny to say this," Newell says, "but we get a better return right now by focusing on those features and technologies that are about community, about connecting people together."

He cites easy uploading of gameplay videos to YouTube as a bigger source of entertainment value than marginal improvements in graphics. "I think that people thinking about how to generate web hits on their servers are a lot closer to the right mentality for what's going to be successful in entertainment going forward, than somebody that's used to having conversations about how to get end caps at Best Buy."

The revolution in distribution and business models also offers a major new opportunity for smaller games - and smaller games developers - to thrive. The demands of retail - the logistical problems of getting boxes to shops, and the budgetary drain of huge marketing campaigns - mean that bigger is necessarily better in the traditional games market.

"You're getting back to an area where smaller and smaller groups can connect with customers. I think you're going to find that the enjoyment of being in the game industry as a developer on the PC is a lot greater than outside of it."

Gabe Newell

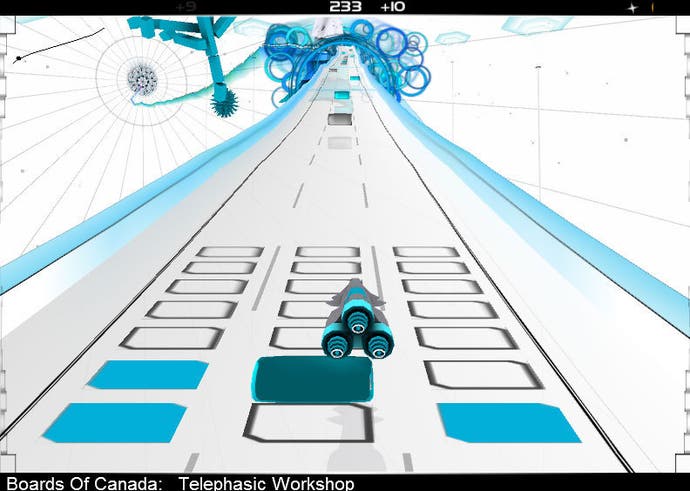

Not so on Steam and its equivalents, says Valve, pointing to the huge success of indie darling Audiosurf, as well as its own Portal. "As you move away from that huge first weekend, big blockbuster mentality," says Newell, "you're getting back to an area where smaller and smaller groups can connect with customers. I think you're going to find that the enjoyment of being in the game industry as a developer on the PC is a lot greater than outside of it."

He's backed up by an actual indie, Audiosurf creator Dylan Fitterer. This one-man development, created without financial backing - impossible on consoles, due to the cost of development kits - was the best-selling game on Steam full-stop at its release, outclassing many big-budget titles. "I didn't have to ask anybody if I could release it, except for my wife," Fitterer says. "It took a few years, and I was pretty darn tired by the time it was ready. Something like certifications? No thanks." He also points out the tight limitations of console servers versus PC servers for online gaming; Audiosurf's scoreboard for every song ever recorded would be out of the question on a closed platform.

Holtman argues that Steam and Steamworks - the suite of free tools it offers - revolutionise the environment for developers and publishers. The auto-updating system means that a game can be developed right up to release and beyond. It eases painful crunch times, and allows game makers to respond to their audiences, publishers to develop their titles as continuously evolving franchises rather than finite products.

"All of a sudden, PC games become this thing that's reliable and up-to-date," says Holtman. Team Fortress 2 designer Robin Walker weighs in, noting that the PC version of the shooter has had no less than 53 updates since its release last year - something that certification cost and time have prohibited for on console - and that this "ship continuously" ethos is a key component to the success of the best multiplayer titles. Steam, he says, makes that process fast and transparent.

"I don't want anyone between me and my customers," says Walker. "I want to write code today and I want all my customers running it tomorrow." Possible on the PC - Steam in particular, naturally. Not possible on consoles. For his part, Fitterer added achievements to Audiosurf in a total of two days. This constant iteration creates a feedback loop between developer and customer that, reckons Walker, can only improve the quality of the game. "The more I talk to my customers, the better my decisions will be. Without a system of talking to my customers, I will make bad decisions."

The implication is a striking one: sporadic, excessively controlled updating means that console multiplayer games will never reach the heights of their PC counterparts. There is a counter-argument - that PC games descend into a poorly defined, indistinct mess of constant patching - but it is effectively squashed by the fact that, if you look for a multiplayer game with the longevity and massive popularity of a WOW or a Counter-Strike on console, you won't find one (with the very arguable exception of Halo).

Auto-updating is the reason Valve created Steam in the first place. It's the reason it now finds itself in an odd position for a developer: semi-publisher, leading distributor, market analyst, agony uncle and technocrat - not to mention defender of a platform that's still being proclaimed dead, when all signs point to the very opposite.

At the end of the day, PC gaming's health - and its trickiest challenge - comes down to a bottom line that even the format's detractors can't refute: there are just so many of the damn things. "We think the number of connected PC gamers we are selling our products to dwarf the current generation of consoles put together," states Newell. "There are tremendous opportunities in figuring out how to reach out to those customers."

This article was originally published on 27th June 2008.