13 years later, Spider-Man 2's swinging has never been bettered - here's its story

With great power comes great responsibility.

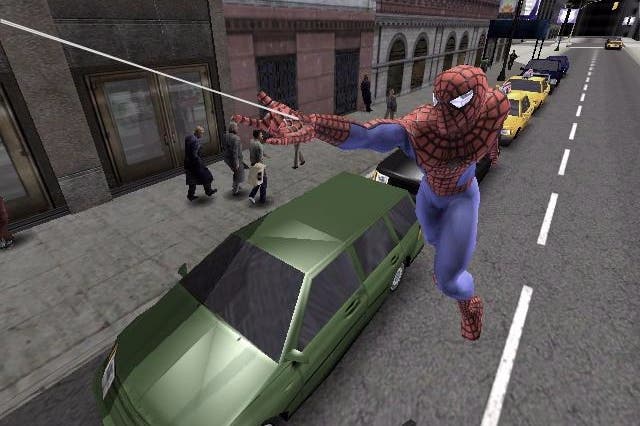

Treyarch's Spider-Man 2 was first released on 28 June 2004. More than 13 years later, it still holds up as a yardstick for both Spider-Man and superhero video games. But it's not the combat people remember. It's not the balloon kid or pizza delivery side missions. It's not the amazing cast of villains, either. It's the swinging, the sheer exhilaration of flying over, around, between and often smack into buildings. Spider-Man 2 is a tantalising playground of needles to thread, a true-to-life Spidey simulation - and we have a designer called Jamie Fristrom to thank for it.

Fristrom came up with the idea for Spider-Man 2's swinging system, built its prototype and piloted it to completion as technical director. He created one of gaming's most beloved and enduring movement systems, and he did it nearly a year before Spider-Man 2's development began in earnest.

"It was something I wanted to get in on Spider-Man 1," Fristrom says. "I think we were about six months into Spider-Man 1's development and I wasn't happy with the swinging as it was. It's practically flying with just cosmetic webs shooting up to the sky. I wanted something a little more realistic. But the prototype I managed to come up with then was pretty crappy, so we did not switch horses mid-stream."

There was no true precedent for what Fristrom was trying to build. He was inspired by 1996's Rocket Jockey, a racer about cars with grappling hooks on either side. "You could either use them to attach to a pole and whip around the pole, or attach to a beach ball and pull the beach ball into the goal," Fristrom explains. "And that fit my tastes because those grappling hooks were ropes with hooks and inertia and momentum."

He began by manually placing swing points at the corners of buildings. It was a start, but it was inflexible. In play tests, players would often accidentally stick to the walls between the points. It felt clunky, so he and his team tried adding more points.

"It was another designer, [Eric Pavone], who put more and more points in the world - on the walls, all over the place," he says. "We started putting hundreds of points in and we were like, 'yep, the more points you add, the better it gets.' "

Adding infinite points would have been ideal, but it was impossible due to hardware restrictions (Spider-Man 2 was built for the GameCube, PlayStation 2 and original Xbox). So, Fristrom and his team got creative, and with the help of programmer Andrei Pokrovsky soon found a workaround: raycasting.

Fundamentally, raycasting is about using radiating rays to scan physical geometry. The original Doom used it to render its environments in relation to the player, but Fristrom and his team were using it more like echolocation, a way to detect suitable swing points. This allowed players to swing from wherever the rays intersected with the game world, including the corners and sides of buildings, providing functionally infinite swing points. With that, Fristrom had finally bagged his white whale. He was ready to take it to management.

"The Activision producer looked at it for the first time and he was obviously loving it," Fristrom remembers. "He was sticking his tongue out, he had gamer face as he was trying to catch up to a moving object. So, he brought his boss in to show the game to. Then they brought their boss in. And it went all the way up to Ron Doornink, who was the COO of Activision, all in one day. And they were all really excited, and that was just awesome. It was like, all this work we put in is actually going to happen."

Wait, Activision loved the swinging system? The same swinging system every game since Spider-Man 2 abandoned? Spider-Man 3, Web of Shadows, Shattered dimensions and Edge of Time were all published by Activision, but none of them had the same swinging. We were back to just flying through air. Why?

"I've got no explanation for that," Fristrom says, adding that Spider-Man 2 actually sold fewer copies than its predecessor. In an old Reddit thread, he offered another explanation, which he upheld when I spoke with him.

"It reminds me of Coke and Pepsi," he wrote. "Most focus testers, given just a couple of sips of Pepsi, preferred Pepsi. Because it was sweeter, right? But if you actually sent people home with a case of Coke and a case of Pepsi, most people preferred Coke, because over time, Pepsi is too cloying and too sweet. Same thing here... somebody new coming to the system will be like, 'yeah, look how cool and badass I am right out of the gate!' But after playing it for a while will be like, 'okay, I'm bored now.' "

In its pursuit of mass-market appeal, Activision threw out what most consider to be the secret ingredient to the Spider-Man video game recipe. Fristrom says he can't refute it as a business strategy, but it was still disappointing. In fact, the suffocating idea of playing it safe played a big part in him leaving Spider-Man 3 mid-development.

"There were a bunch of little things that made me want to quit. My contract was up, I had some new opportunities. But there was one thing at Activision.

"I really liked the stealth levels from the Neversoft Spider-Man game [on the original PlayStation], and I wanted some different types of gameplay to change it up. So, I had a sub-team and we were working on some stealth levels where you crawl along the ceiling, there'd be guards underneath you, you'd drop down, grab them, go up to the ceiling, web them up and move on. Or just crawl over their heads and try not to get noticed.

"A bunch of us in the studio thought those stealth levels were really cool, but a bunch of people were like, 'no, people aren't going to get this.' I didn't have the energy to fight for it. So that went away, and after that was gone I lost enthusiasm for the project.

"And to blow my own horn, and it wasn't there yet, but there was a hint of what you'd see later in the stealth missions in the Batman: Arkham games. Just the idea of being above the guards and having these moments where you take them out and the others wonder what's going on.

"In a way, I feel a bit vindicated after playing those games, like, 'yes, this could have worked, people would have loved it and it would have sold well.'"

After leaving Activision, Fristrom founded Happion Laboratories, where he made Energy Hook, a 3D platformer explicitly couched in Spider-Man 2's swinging mechanics. He also made Sixty Second Shooter, an experimental twin-stick shooter played in one-minute bursts. Recently, he's taken to tinkering with Roblox. His latest project is Castle Heart, a MOBA-lite action game. He hopes to one day make a Diablo-esque action-RPG. We'll see more games from him, he says, but nothing AAA. Fristrom says he's in semi-retirement, and he's happy being "the Spider-Man 2 guy".

"I have managed to brand myself, and that's probably because I've just bragged more than other people on the team," he says. "It was a group effort. Yeah, I did the first couple prototypes, I got the ball rolling. But then so many other people worked on it. If it had just been me, it would have been crap. Everybody working on it together lifted it up and made it what it was. That's important to remember."