20 years of PlayStation: Japan's war on cliché

The exotic wonder of PlayStation's Japanese curios.

Every time I opened a new Japanese import PlayStation game (which happened at a rate of around once per week when I had a student loan to naively plunder and the majestic expanse of a teenager's summer holiday to fill) I'd open the manual, press my nose to the staples and take a full breath.

The booklets have a unique scent (rounded, inky) and today, like the perfume of a bygone lover, their smell can instantly summon the colour and contour of that otherwise lost time. The trigger is particularly strong because these exotic games offered a refuge at a time when the rest of my life was chaotic. They provided a sanctuary and, in their systems, reliability that was absent elsewhere. After a while they began to smell like home, or the promise of it, at least.

I mention this because I'm not sure whether the PlayStation's library of games is necessarily the best of any video game console. But for me, it remains the most vital and fondly remembered. Even though so many of the PlayStation's games have aged terribly (debuting, as they did, on the frontline of 3D's emergence), it's a line-up that has, for me, never been bettered. Our favourite video games, like our favourite songs or novels, are often the ones that showed up at the moment they were needed; they helped, in some mystical way, and our gratitude endures. So it was with Einhander, with Xenogears, with Rival Schools, with Treasures of the Deep and all the reassuringly fragrant others.

It was the ritual of the process too - a ritual that, sadly, is no longer available to the exotic game hunter in London. At the time I lived a walking distance from Computer Exchange ("kecks", for short) in Rathbone Place, a shop that was stocked with a seemingly ceaseless supply of unusual games imported from Japan. Today the old spirit of the place is long gone (even if the pocked aluminium floors and murk remain). DVDs have replaced the rows of retro games in the basement; the video game treasures that once sat behind protective glass (a signed copy of Metal Gear on the MSX, a pristine Metal Slug in that prestigious Neo Geo casing) have been swapped for a miserable phalanx of mobile phones and smeary tablets. But back then an entire wall was given over to Japanese PlayStation imports, a library of rare potential.

I'd visit each week, flick through the spines in search of a game that might be playable for a non-Japanese speaker and then carry it home in that way you can only ever carry a video game home: filled with excitement at its unblemished potential and fantastical promise, this portal to another world, contained in a rucksack. Video games, in their breakthrough into 3D, had entered a new and mystical place, and nowhere were game-makers exploring the territory with such force and joy as on PlayStation. To be an importer in the late 1990s was to bear witness to the breaking of new digital frontiers, months or years before the rest of the world reached them.

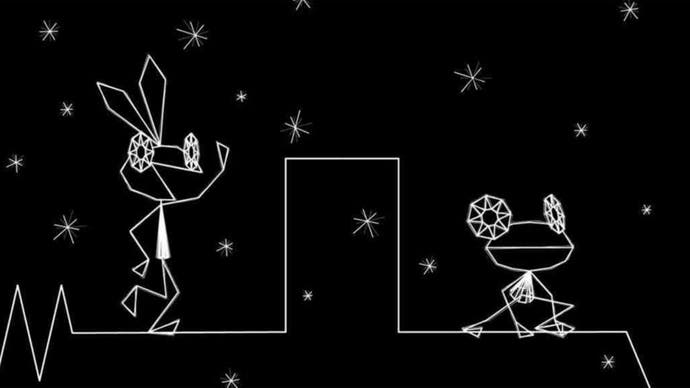

We remember the Japanese big hitters of the time fondly: the trio of Final Fantasies, the duo of Gran Turismos, Metal Gear Solid (which CEX sold to me under the table; Sony had reportedly threatened legal action to importers who sold the game ahead of its British release), the Pro Evos, the Tekkens and so on. But what made this period magical were the curios, which were considered too strange and wild for western eyes. Sony Music's guiding hand on PlayStation's relations with developers in Japan was crucial: this arm of the company understood that creative talent should be encouraged and nurtured in way that Sony's technology-focused core did not. The result was an uprising of independent studios who were encouraged and financially incentivised to try the unexpected. The result was PaRappa the Rapper, it was WipeOut and Jumping Flash.

This period, with all its exoticism, when video games seemed as though they could go anywhere and be anything, is reminiscent of the best of the independent game scene today. But the difference was that here Japan's major publishers embodied the spirit. Incentivised by Sony's competitive royalty deals, which drastically undercut Nintendo, they brought with them financial clout to paint their visions in full, often without compromise, in a way that only the best-funded independent game-makers are able to do today.

For example, Final Fantasy's publisher Squaresoft demonstrated unprecedented ambition at the time, with games such as Bushido Blade, the one on one fighting game in which a match could be decided on a single, well-placed sword strike, and Brave Fencer Musashiden, one of the first games to create a world that ticked to an internal clock, with shops that were only open at certain times of the day. There was Einhander, one of the greatest horizontal scrolling shooters of the day, made by a team with no experience of the genre and Internal Section, an ode to Jeff Minter's psychedelic long-dives into the screen. There was Racing Lagoon, an RPG-racing game tribute to Yokohama's wide-boy street racing culture. The company even launched a separate label, Aques, to release PlayStation games that were too unusual for its mainline releases -- something that would be unthinkable today.

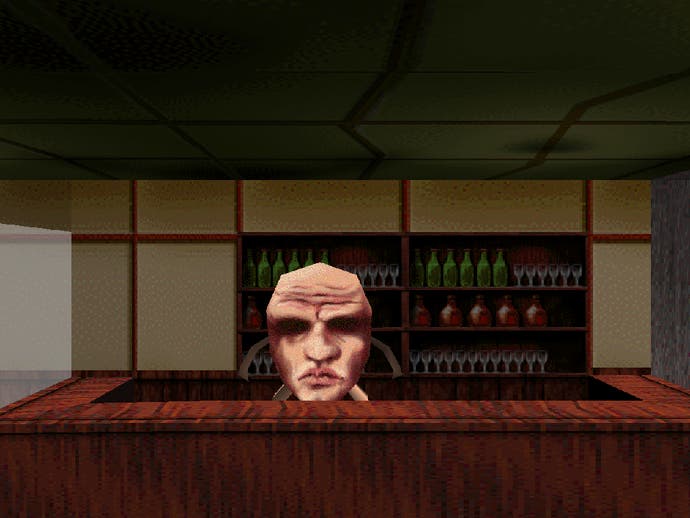

Namco made Treasures of the Deep, a diving game in which you swam through wrecks hunting for treasure while praying you wouldn't be noticed by nearby predators. The company's future collaborator, Bandai, funded Silent Bomber, a top down version of Spy vs. Spy as seen through the eyes of Akira. Sony published The Book of Watermarks, a Myst-like exploration game featuring the Celtic folk singer Moya Brenna, in which I lost a memorable few weeks (the game's artwork, printed on thick tracing paper, was exquisite).

There was Pepsiman, a game in which you played as a lycra-wearing soft drinks mascot, sprinting through Japanese streets collecting cans. And this was the dawn of the Densha de Go era, in which everyone had the chance to become a Tokyo subway driver, sweating Shinkansens with anxiety that you'd arrive at the next station more than five seconds behind schedule. And there was Bishi Bashi Special, a micro-game collection of un-moderated lunacy and wonder, rivalled only perhaps by WarioWare.

The inquisitive invention wasn't limited to Japan, of course. In England Codemasters launched TOCA Touring Cars, an unexpected racing game with a peculiarly British style (and weather), while Psygnosis supplemented its era-defining work on WipeOut with Rollcage, a game in which it was possible to drive along the walls and ceilings of the screen. But Japan was the power centre of novelty and invention. While Capcom's console heyday was undoubtedly on the Dreamcast, the company launched Rival Schools on the PlayStation, a high-school base fighting game in which different cliques battled using their particular strengths, be that synchronised swimming, violin playing, or baseball. No major game publisher would fund a game like LSD Dream Emulator, which was based on a dream journal one of Asmik Ace Entertainment's staff members had kept for a decade, anywhere outside of Tokyo in 1998. Nor Incredible Crisis, a game that follows members of a working-class Japanese family as they race to buy their grandmother a birthday present before the end of the day.

I remember this era with such fondness not only because of the place it had in my own story (playing Super Puzzle Fighter with my friends into the early hours when we should have been revising, bonding with my brother as we climbed the ranks in Smash Court Tennis, high-fiving every point) but also because of the place it has in the medium's story. This was a time of vibrant creativity in mainstream video game publishing, one that no longer exists.

As the cost of producing games has risen, and the power base of video game commerce has shifted to America, the kind of vibrant risk-taking that resulted in Ape Escape, Parasite Eve, MDK or Vib-Ribbon is gone, or at least, gone from shop shelves (along, in many cases, with the shops themselves), relegated to the depths of Steam. This period, from 1994 through to the early 2000s saw Sony enable an unprecedented and, arguably, un-replicable time of creativity in the industry. The games were often scrappy and unrefined. But they were also unusual and memorable, attributes that, alas, cannot be imported in a day-one patch.