40 years on, celebrating the Mattel Intellivision

The visionary console that tried to take on the mighty Atari.

I tried to hide my disappointment, but I couldn't. It was Christmas, 1983 and I wanted a ZX Spectrum. All my friends either had one, or were also desperately hoping one would be sitting under the tree. Instead, for reasons which my parents have never satisfactorily explained (it was probably on special offer), I got a Mattel Intellivision console. In the four years since between its release in 1979 and that fateful yuletide morning, the Intellivision had already played out its own rise and fall.

While I pined for a Speccy, in truth the Intellivision's chief opponent was another console entirely. Not that there was much competition - the Atari VCS was an all-conquering behemoth of a console, its shadow drawing long and wide across the world of videogames. It revolutionised home gaming. But the popularity of the VCS didn't scare away other manufacturers, and one eager outfit was veteran toy company, Mattel.

Mattel - the name a compound of the names of owners Harold Matson and Elliot Handler - had been founded in 1945, and in an era keen to forget the horrors of World War 2, proved successful, especially with its range of Barbie fashion dolls. But by the mid-70s, Mattel's younger executives were pushing for the company to branch into electronic toys, initially handheld LED games such as Auto Race and Baseball. These early efforts met with mixed results while development of an interchangeable cartridge-based system began in earnest in 1978.

With Mattel's head of design and development, Richard Chang, overseeing, APh Technology Consultants was employed to design the system's operating system while Mattel's own Dave Chandler headed up a team to model the machine itself. At APh, Dave Rolfe worked on both the machine's OS (dubbed the 'executive' or 'exec'), and developed one of its first games, Baseball.

With the VCS having been released the previous year, Mattel had a good idea of what it was up against, and how it could improve on the Atari console: better graphics, the aforementioned integral operating system and a more complex controller to allow deeper games.

The executive would encompass a graphics ROM that contained a series of standard images - such as the famous running man - which could then be used by games in order to save cartridge memory, a constant battle of the format. The famous look of the console, partly inspired by the Atari 'Woody', included a faux wood grain strip and its brace of built-in controllers. Power and aerial sockets plus a side-loading cartridge slot completed the trimmings before release in 1979, a limited test run within California that proved successful enough to see it on shelves worldwide by 1980.

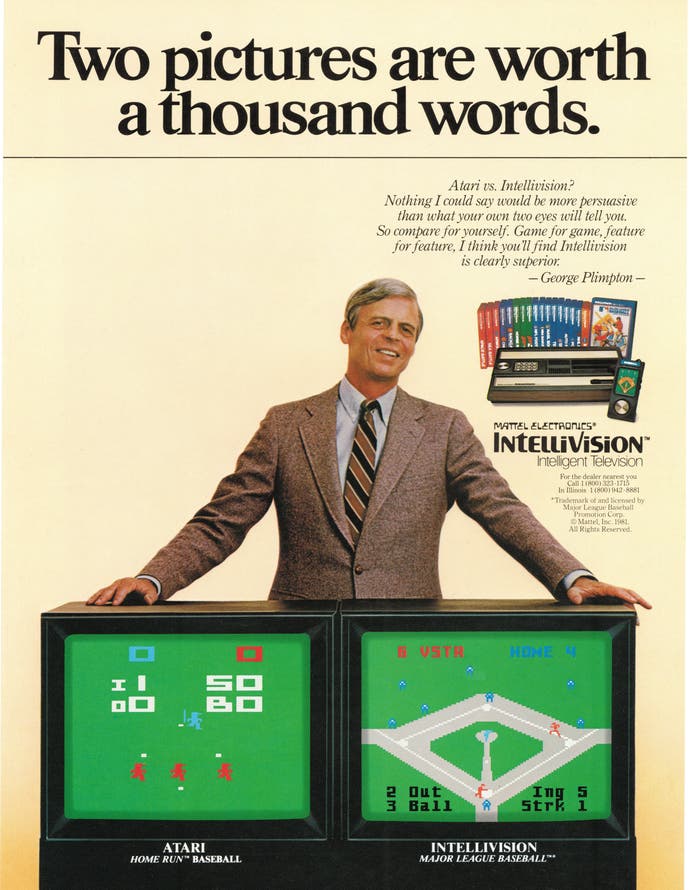

The battle had begun, although it was a conflict that would be mainly fought in Atari and Mattel's respective marketing departments. A famous advertisement, featuring sports writer George Plimpton, pointedly baited Atari by comparing its blocky baseball game to the Intellivision's own officially-licensed effort. 'Two pictures are worth a thousand words' was the headline quote from Plimpton, and even today the difference between the two simulations is stark. Yet with it retailing at a wallet-busting $299, the Intellivision (an amalgam of the words intelligent and television) was initially hamstrung on price and its lack of recognisable gaming properties. In an inspired move, it focused on officially licensed sports games, common today, but an unknown marketing ploy in the late 70s. In addition to Major League Baseball, titles such as PBA Bowling, NFL Football, PGA Golf and NASL Soccer proved to be among the console's most impressive sellers, and compelled Mattel to begin assembling its own team of coders.

Gabriel Baum, poached from Thorn-EMI London by Mattel president Josh Denham, began work in January 1981, hiring the people he thought best, coders with a logical creative vision, and an ability to not only design, but design obsessively. Its members would include the creators of several ground-breaking games: Don Daglow, Rick Levine, John Sohl and Keith Robinson. The latter, having come aboard to help design one of three Intellivision games based on the Disney movie Tron, was soon promoted to manager, overseeing development of Mattel's in-house games - a swift promotion that encapsulates the frantic nature of software production in the early 80s.

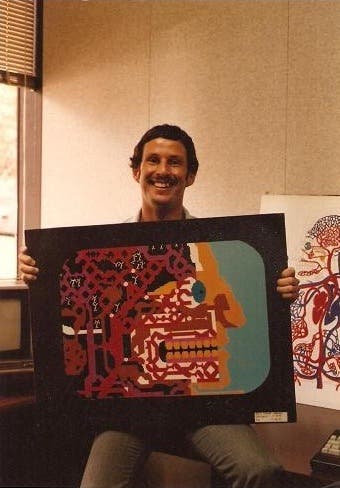

And the team continued to produce fantastic games, notably more elaborate than those on the Atari 2600: Daglow's Utopia introduced real-time strategy coupled with the God simulation genre, while Levine's background in the medical profession helped him create the beautiful medical emergency thriller, Microsurgeon. Even a seemingly humble shoot-'em-up such as Astrosmash, by John Sohl, contained a then-unique score attack mechanic, as the player balanced attack and defence with its finely-tuned risk-reward gameplay. The maligned controller, along with the on-board operating system, enabled these games and more to exist. "Once you got used to the operating system, it was great, and quick to get something on screen," the late Robinson told me in 2015. This system - the exec - was essentially a game loop, with the program a group of subroutines automatically called upon when certain events, such as a collision, occurred. It wasn't perfect, but for those who learned how to work with rather than against it, it performed well, with a skilled coder even able to bypass the exec loop and create new and different special effects or events.

The Intellivision was a pioneer that made history - even if some of that history was the more questionable kind that the likes of Sega would have done well to study when it was churning out bolt-on hardware for the Mega Drive. Mattel had made those mistakes already. The master component unit, the Intellivision itself, was deemed to be just the start by Dave Chandler and his production team. In continually working on ways to expand the use of the console, Mattel devised concepts and hardware that, while unsuccessful in terms of sales, broke new ground in games and the way they were played.

Foremost was the Intellivoice, a small device that plugged into the cartridge slot and enabled programmers to place speech into their games. Even more prognostic was the PlayCable unit, a concept of startling foresight that permitted games to be downloaded to the Intellivision via cable TV. Most ambitiously, Mattel planned a keyboard component, effectively transforming the console into a home computer, but this endured a troubled gestation and was unreleased bar a few units sold via mail order. All these peripherals were seen as vital by Mattel management as it sought to grab consumer attention in an increasingly-swamped market. Lack of software support doomed them all to failure, yet there was an even more foreboding shadow on the horizon.

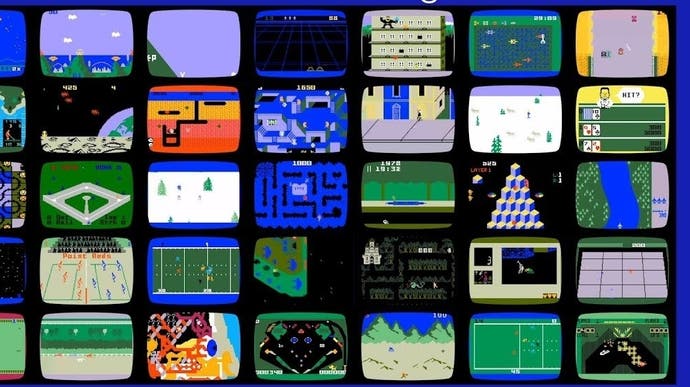

The US video game market had been expanding rapidly since Atari's success of the late 70s and early 80s. Like Atari and Coleco, Mattel was hardware manufacturer, and its consoles were sold with tight margins. Mattel's own games brought in money, but those created by third-parties were of no direct help to its shrinking bank balance. "By 1983, the Intellivoice, Entertainment Computer Module, Aquarius, Intellivision 3 and other hardware were all either marketed or in development at Mattel," said Robinson back in 2015. "But they couldn't sell enough games to cover the expenses. Had they concentrated on the original Intellivision console and games, then maybe they could have survived, essentially what INTV Corp. did." Formed shortly after Mattel closed its electronics division, INTV was run by an erstwhile Mattel senior vice-president, Terry Valeski. Purchasing the brand, rights and assets, INTV oversaw an extended period for the Intellivision, releasing over 30 new games between 1984 and 1990, when the console was finally retired.

While far from a perfect story of how to develop and market a games console, the Intellivision remains pioneering in many respects. Home to a small collection of games that were often remarkably in-depth as well as fun, its ill-fated and random array of add-ons were well-intentioned and forward-looking.

"The group of people who worked on the Intellivision were creative, smart and funny," said Robinson in 2015, "and I think that is why so many of the games are still so fun." In the final analysis and cold light of 2019, 40 years after the Intellivision first saw the inside of electronics stores in Fresno, California, it's clear the console failed to compete with the Atari to any significant degree.

Yet despite this apparent defeat, it has inspired a new version, the Amico, due for release in 2020. Led by industry veteran Tommy Tallarico, the Amico will include many Intellivision classics built-in with further games available from a bespoke online store. How it will be received in a world of PlayStation 4s and Xbox Ones remains to be seen; but for those of us that did own one of those beautiful master components, complete with its futuristic gold strips and dark plastic, it sparks memories of a console that was a true pioneer.