A brief history of cyberpunk games

Chips with everything.

The long-awaited release of Cyberpunk 2077 brings to an end years of feverish anticipation for those who have been itching to roam the streets of Night City, but it's only the latest example of gaming's fixation with the trappings of the cyberpunk genre.

It's perhaps inevitable that gaming and cyberpunk are so closely entwined, given that both were birthed in the technological boom of the 1950s and gained mainstream pop culture presence around the same time in the late 70s and early 80s. The hard part is working out how to separate the games that cherry-picked aspects of the cyberpunk aesthetic - of which there are literally hundreds - from those that are, or at least attempted to be, genuine examples of cyberpunk fiction. For that, we need to nail down the genre's key tropes; namely a dystopian outlook on the near-future, an interest in alternate digital realities, drug or technology assisted human modification, and a cultural milieu in which corporate interests have long since outranked the quaint notion of elected government.

Things got started pretty early, with adaptations of 1980s cyberpunk movies for 8-bit home computers like the ZX Spectrum. The Blade Runner game, rather cunningly, was licensed from the eerie synth score by Vangelis rather than the more costly movie despite asking you to fly your "Spinner" craft over Los Angeles, locating errant replicants then chasing them down in simple foot chases. An amusing distraction, but one that failed to grapple with the themes of cyberpunk in any meaningful way.

The Max Headroom game, released in 1986 and based not on the MTV-styled chat show but the original Channel 4 TV movie - itself one of the sorely underrated cyberpunk texts - cast you as a hacker infiltrating the offices of a sinister media corporation. This brainwashing outfit is keeping Max, the world's first digital intelligence, captive on its mainframes and it's up to you to liberate him. Ascend through all the floors, beating security systems and hacking elevators, and you were rewarded with an animated scene of Max thanking you personally through the medium of distorted sampled speech, a ground-breaking multimedia feast at the time.

The ideas behind cyberpunk were a key part of Max Headroom's TV debut but weren't really explored in his game. Nor would they be in 1991's D/Generation, for the PC and Commodore Amiga, a game that was very similar to Max Headroom in both concept and execution. You were once again a hapless interloper - this time a courier - trapped inside the skyscraper of Genoq, yet another a dystopian corporation, forced to battle floor by floor to reach the end against an army of blobby bioweapons. The gameplay was a little more sophisticated, the plot a tiny bit more pretentious (your character is named after philosopher Jacques Derrida) but ultimately all you were doing was blasting monsters and solving puzzles. Cyberpunk, as an ethos, was still just window dressing for familiar pleasures.

That all changed, finally, in the 1990s as the rise of internet technology collided with the widespread western releases of Japanese anime titles such as Akira and Ghost in the Shell, creating a perfect real world petri dish in which simmering cyberpunk concepts could come to a culturally relevant boil. As a result, in 1993 and 1994 alone we got four key cyberpunk games whose influence is still being felt today.

1993's Syndicate, Bullfrog's ultra-violent squad strategy-shooter, was arguably the first game to be cyberpunk in both concept and content. Set in the year 2096, Syndicate imagined a world in which the world's government's have been subsumed by gigantic mega-corporations, and the populace kept compliant through the use of implants that leave people oblivious to the dystopian hellscape they inhabit.

Where Syndicate deviated from cyberpunk stories in prose and live action was that this time, in keeping with gaming's bloodthirsty edge, you were an enthusiastic advocate for the bad guys. Controlling a quartet of bio-enhanced agents from an isometric elevated view, your task was to venture across bleak cityscapes to complete missions for your corporate paymasters, sabotaging rival megacorps and generally wreaking havoc with an array of weaponry and gadgets to advance your agenda. Among these gizmos was the infamous Persuadertron, which allowed you to flip the allegiance of NPCs thanks to their chip implants, a truly dark and brilliant cyberpunk conceit.

The same year also saw the SNES release of one of gaming's seminal cyberpunk franchises, Shadowrun. Splicing a little Japanese role-playing DNA into the genre, along with tropes from Tolkienesque high fantasy, Shadowrun was also an early example of the crossover between tabletop gaming and video games.

Playing as amnesiac protagonist Jake Armitage, you were dropped into Seattle in the year 2050, although in Shadowrun's reality mythical creatures like orks and elves share our cities, and high-tech body modifications co-exist with magic. It's one of those genre mash-ups that could easily have turned to sludge, but the result was genuinely fascinating, using another popular post-Blade Runner cyberpunk trope - the film noir detective mystery laced with sci-fi - to immerse you in its unusual world. The game also offers another recurring cyberpunk idea, popularised by William Gibson's 1981 short story Johnny Mnemonic, with Jake revealed to be a "data courier" who transports sensitive information via a hard drive in his brain.

Johnny Mnemonic got a movie adaptation in 1995, in which Keanu Reeves communed with a cyborg dolphin, which also inspired a point-and-click adventure game the same year, but prior to that two more seminal - and original - cyberpunk tales were told through gaming.

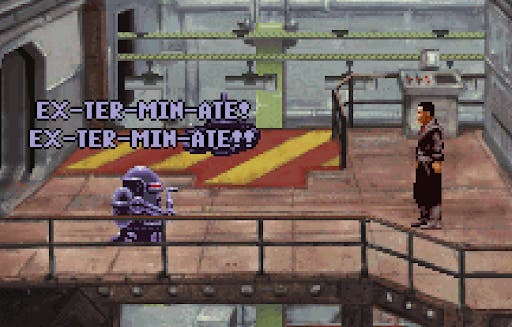

Beneath a Steel Sky was a 1994 collaboration between legendary adventure game designer Charles Cecil, he of Broken Sword fame, and Watchmen comic book artist Dave Gibbons. Set in yet another dystopian vision of our future, with the world divided up into vast city-states dotted across desolate continents, Beneath a Steel Sky balanced the expected nihilism of the cyberpunk genre with a wry sense of humour expected by gamers weaned on Lucasarts adventure games. Most notably, the game explored the idea of sentient machines - both through a humorous vacuum cleaner robot sidekick and a rather grim endgame revelation regarding the nature of LINC, the city-controlling AI behind the scenes.

As a graphic adventure, Beneath a Steel Sky was able to foreground story in a way that previous cyberpunk-infused games hadn't, and it was an emphasis that also ran through 1994's other genre-defining game: System Shock.

Set in the year 2072, System Shock had you playing as a nameless hacker blackmailed by a rogue executive from the TriOptimum Corporation into extracting information on a new bioweapon from SHODAN, the AI that controls Citadel Station. That synopsis alone already places System Shock squarely in cyberpunk territory, and the game's first-person perspective and non-linear construction gave players plenty of agency to rummage around and explore its implications. The game also unfurled in the real world - "meatspace" - and the digital realm of cyberspace. At a time when the very notion of websites was seen as thrilling and new, this cannot be underestimated.

More important still was the freedom the game gave players to define and upgrade themselves over the course of the game, depending on their preferred style of play. It's a mechanic that we take for granted today, seen in everything from historical brawlers to fantasy RPGs, but System Shock pioneered this notion of the player character as a living canvas onto which different skills and abilities could be added through implants. What had been a background concept in earlier titles was now a core gameplay idea, and it's no exaggeration to say that gaming would never be the same once System Shock normalised it. Few are the AAA games where upgrades and skill trees don't feature these days, and the very concept is cyberpunk to its core. Can't do something? Enhance yourself until you can.

Even in games that weren't immersed in cyberpunk culture, the themes of rampant corporations, technological subterfuge and dystopian futures were now well baked into gaming in general, as exemplified by G-Police, a 1997 PlayStation exclusive in which you controlled a futuristic hover-copter swooping through the domed colonies of Callisto. The gameplay was pure power fantasy wish-fulfilment, but the conceptual debt to Blade Runner's cityscapes and a storyline that eventually led to the expected corporate malfeasance are just enough to tip the game into the margins of the cyberpunk genre, even if the narrative idea that weaponised surveillance attack craft are a bad thing sat uncomfortably with the fact that, in terms of play, they're actually awesome.

Strangely, while the turn of the millennium saw a fresh wave of cyberpunk inspired movies - The Matrix and Strange Days especially - the genre died down a little in gaming, or at least the innovations that peaked in the mid-90s were noticeably absent. Deus Ex is the sole shining beacon, released in 2000 and created by Warren Spector, producer on System Shock. Very much a spiritual sibling of that game in both concept and execution, this time you were playing as JC Denton, an agent of the United Nations Anti-Terrorist Coalition (UNATCO), hot on the trail of a lethal nano-plague.

The augmentation aspect of System Shock was given free rein here. Traditionally in cyberpunk the idea of implants and upgrades was one that gave the underdog a fighting chance against a corrupt and oppressive state, or allowed for criminal acts such as data smuggling. In the world of Deus Ex, it was the gateway to superpowers - strength, speed, stealth - that would make the average comic book hero blush.

Deus Ex also leaned hard into the realm of conspiracy theory, taking the suspicion of authority inherent in the genre and dialling it up to 11 with overt references to Area 51, the Illuminati and more. The story builds to a moral choice with global implications, but it wouldn't be until 2011's Deus Ex: Mankind Divided that the series really dug into the philosophies behind cyberpunk, fully exploring the ramifications of having augmented superhumans running around.

Following Deus Ex and its immediate sequel, cyberpunk receded to become an aesthetic choice rather than thematic obsession for gaming. Titles like Fear Effect and its sequel riffed on the style but seemed more interested in goosing media coverage through its priapic lads-mag lesbian lead characters. Sci-fi demon-mashing game Oni, a collaboration between developer Bungie and publisher Rockstar, was decent enough in terms of action but was ultimately just borrowing Ghost in the Shell's clothes to dress up old gameplay concepts.

Surprisingly, the game that best explored cyberpunk themes in the 2000s, prior to Cyberpunk 2077 itself, was one that ditched almost all of the now-cliched visual signifiers of the genre. As another data courier fleeing authoritarian forces, Mirror's Edge distinguished itself by imagining a world where corporate control has resulted in a sort of stifling peace, its lofty skyscrapers revealed in brilliant whites against clear blue skies, jolts of red showing you the parkour pathways you'd use to escape the system. With no neon signs, no trudging brain-wired figures in rain-soaked streets, Mirror's Edge looks nothing like a typical cyberpunk game, yet its story of smothering control and digitally-assisted rebellion was arguably one of the last major publisher releases to sink its teeth into the themes that had defined the genre all the way back in late 70s and early 80s.

Which brings us to today, and the imminent arrival of Cyberpunk 2077. The game arrives carrying an enormous amount of hype on its augmented bionic back, and with its first-person view, spiralling customisation options and emphasis on freedom of choice it's clearly setting itself up to join the pantheon of System Shock and Deus Ex. Yet it's also a multi-million dollar AAA entertainment product, developed and published by what are now major corporations. Such is the dichotomy of exploring cyberpunk through entertainment media. Here's hoping Cyberpunk 2077 can live up to its ancestors - and the promise of its own title.