A Highland Song review - a magical sonnet hidden beneath a game

Peak performance.

A surprise discovery I made a little way into A Highland Song, the latest from Overboard and Heaven's Vault developer Inkle: it doesn't matter if you fall off a cliff. This, I think, is quite weird for a climbing game. And especially one where a sense of peril seems at first to be such a central part of what it's trying to do. As a girl named Moira, you must run from a miserable home in the Scottish highlands to visit your uncle, at a faraway lighthouse. You spend a week, or probably more, scrabbling up the side of mountains, sheltering from storms in cave mouths, spelunking into dead ends in search of directional clues - you've no actual map, by the way - and you do this racing against both a shrinking health bar and each day's ever-fading sun.

But! No actual peril. Fall off or run out of health and you just pop back to where you were before. The result, combined with a few other snags, makes for a less than stellar game about hiking, or survival, or indeed climbing. But it makes for a wonderful game about the mountains - about experiencing the natural world, in fact - which is what A Highland Song is really aiming to be.

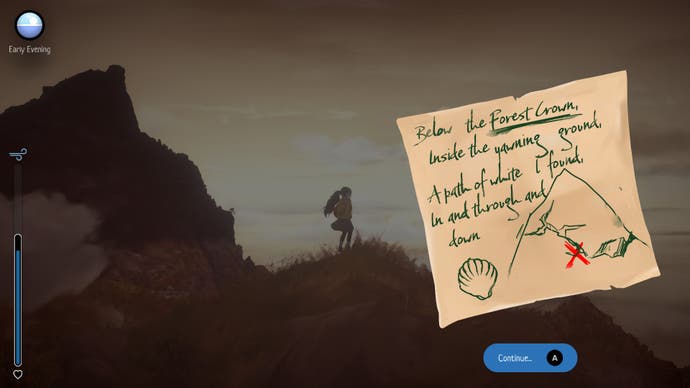

An example: A Highland Song isn't afraid to have you do things without purpose. Along your journey through layered peaks and valleys you'll find items, mostly some form of rubbish, which may or may not prove useful down the line. A discarded crisp packet contains the torn page of a mountain guide, to serve as a makeshift map. A buried key might open a nearby building, for some essential shelter. Or a particularly sturdy stick, which I thought must surely come in handy, may end up with no use at all. Between triumphant trips to mountain peaks you might come across long and tantalising paths to a dead end. A deep cave, say, struggled through for precious minutes - in-game hours - with no way out the other side.

This is all the more impactful when you piece A Highland Songs occasionally discordant mechanics together. Your uncle, Hamish, has been writing you letters through the years, but suddenly he needs you to make it to his lighthouse, at a sea so far away you've never seen it, in seven days. The in-game clock progresses at a decent rate - maybe a game-day in a real-world hour - and Moira is human, so at night she gets tired. An uncomfortable sleep - say, under some open shelter like those cave mouths and overhangs - refills your health bar, but lowers your maximum health at the same time.

Bumps, knocks, falls, or excessive climbing without pausing for breath can chip that health bar away - as can inclement weather, which in rural Scotland is more or less the default. These things can quickly stack up, and combined with a long diversion into nowhere, a search of the endless hills for nothing, they can make for a bruising test of endurance - and patience - while your objective goes from making it to the lighthouse in time, to making it there at all, to honestly giving up and just seeing what you might find next.

You'll spend much of A Highland Song - actually no, all of A Highland Song - not having the faintest clue where you are. You might know the literal name of where you are - much of the game is the actual act of mapping itself, taking those discovered pages, remembered hints from Hamish, and scribbled drawings of your own and comparing them with the environment until you can successfully cross the mountain names off in your notebook - but the difficulty is knowing where the Place Where You Are actually is. As in: how to get from where you are right now, to anywhere else, or if it's even possible to get there at all.

That can be exacerbated at times by A Highland Song's art direction, a sweeping, and utterly stirring pile of mossy brushstrokes that lay atop one another; different, walkable ridges overlapping and interlocking like gauze. Zoom in and they'll blur - there's no up-close texture, you're a ladybird working its way across a great fresco of a mountain range, however you frame it. It's deeply, richly evocative, poetic, and befitting of A Highland Song's carefully chosen words.

But it can be a pain to navigate, on an overcast day, or during the rain, or a storm, or in a cave or either side of the night, particularly when hopping between those layered planes of scalable environment. Or even on a perfectly clear day - the lighthouse is rarely visible, so rarely acts as any kind of reference point. And despite its looks and climbing and vibe, this isn't Breath of the Wild; you can't put a pin in somewhere distant and then go there. You put a pin in it and then go down whatever path you're lucky enough to find, and maybe that takes you there. Maybe you end up somewhere else.

You might, like me, never see that pin again. Altogether, A Highland Song can make its mechanics, its game-ness, too evident. It may occasionally be appropriate for a sense of realism, but with Moira - at least my Moira - often bashing her shin one too many times or simply plummeting into the occasional abyss because I couldn't quite tell whether that rock was climbable background, or just background background, it can grate.

As can the odd song itself, too. Occasionally - and, for me, a little too often - you'll spot a deer, and following it will lead you into a burst of rhythm-game action, as you hop to a jolly tune on prompt, flying through hills that might've taken hours at a regular pace. The issue is this folk music, provided by Laurence Chapman and two Scottish folk groups Talisk and Fourth Moon, doesn't always pair with the tone that came just before, or that follows just after.

When it clicks, these moments are like a prolonged exhale, a wild release as you dash down the far side of a mountain you've spent a tense and precious day climbing. After a couple in quick succession, punctuated by dour and desperate scenes of survival, they can feel like an awkward interruption, a jester bursting in on a funeral. It also doesn't help that they often whisk you off to somewhere entirely new, with little indication of whether that's brought you closer to the lighthouse or actually sent you even further away. A Highland Song is a game of language, but as a result here it's also one of video game language: the unspoken rules ("this is climbable") that lead to unspoken instructions ("you should chase the deer to get closer to your goal") which every dutiful player tries their best to follow. Occasionally that language is too subtle to really understand, which in turn makes it too visible. Think about an unspoken rule too often or too hard and it becomes a conscious burden, a prompt not for clarity but self-doubt.

But then - and I appreciate so far this sounds like a real struggle of a game so far, which in many ways it has been - you will reach the lighthouse. You will also, and this isn't spoiling anything, seriously struggle to get there in just seven days the first time around. But A Highland Song is very much built with multiple playthroughs in mind, and unlike others where that means a bit of extra gear and maybe a "good ending" option if you get things right, those multiple runs are essential to think about as you go. Extract the mystery from it, which anyone who's read a book with a mysterious uncle might be able to guess early enough anyway, and what remains?

Reframed, this is a very different game. One about direct experience over success, exploration over outcome. What kind of story, especially one with a bit of mystery at its heart, needs to be re-read over and over? The answer, at least this time, is one where all the real magic lies in the reading of it, in the richness of the words, the beauty of a world they slowly and deliberately paint into view - as opposed to simply carrying you somewhere final, the bit where you find out what happens in the end. A Highland Song is really, surely, obviously an ode to Nan Shepherd's The Living Mountain, something I only clocked after finishing a run and reading someone else talking about it, and then thinking about what I'd played (and what I hadn't played, but merely thought I had). A book where its author, who roamed the Cairngorms mountain range for years, described her goal in writing it as "to know its essential nature." And then specified: "To know, that is, with the knowledge that is a process of living."

A Highland Song is about what it feels like to be lost in the mountains. Not even lost, in fact. Just to be in the mountains, to have the privilege to exist there just for a bit, to experience them directly and extensively and know them as a process of living. In Moira's case it's over a week, in Shepherd's most of a lifetime. What is Moira here, searching onwards between snippets of poetry, letters, memories, and scribbled, forever incomplete hints of lovers' elopements or quarrels? As she shivvers when the long grass leans around her, and stubbs her toe on another rock, and mutters gallows humour under another sharp draw of breath? I feel like she's my own deer, a MacGuffin or a mechanism, placed to get me moving through A Highland Song's version of nature - to the lighthouse, sure, but not in any hurry. My lighthouse on the next run is just some dead end peak at the edge of the map, or another blocked off cave. An end goal that's just the chance to sit and listen for a minute to wind or running water, and get to know one more corner of such an intimately written world.

A copy of A Highland Song was provided for review by Inkle.