The State of Independence #2

That pulsating crystal thing spilt your pint. Get him.

There's no such thing as a dead genre. Because you can't kill an idea.

This old thought recently occurred again when playing Fahrenheit, which is just a constant lesson in noting that received wisdom isn't actually a list of what works - just what people have been able to make work. Fahrenheit is full of design elements which people have dismissed - timed sequences in adventure games, for example - and yet it makes them sing. This shows that there are few objectively bad ideas in games. And an idea that was once good - really good, the sort of good that changes the world we live in fundamental ways - is good forever.

Such is the case of the shoot-'em-up, or Shmup, as they're affectionately known among devotees (and by people playfully aiming to annoy anyone who gets annoyed by this sort of thing). If it weren't for Space Invaders, we wouldn't be here. It invented the first classical gaming genre, so begetting the modern age. Pong only belongs to a genre as awkward as "sports game", which isn't a real genre anymore than "fantasy games". Space War, by being solely two-player, is a game that uses the computer as a playing field rather than being a videogame artefact in and of itself. The computer as an opponent is one of the things that divide videogames from all previous entertainments.

Increasingly unjustifiable statements that mainly exist so that everyone has something to argue about in the comments thread aside, the point is that the shooter has been here longer than any other. And it has developed; its core components forming the roots of the first-person shooter and its brethren. That's the commercial side of the equation anyway. However, there are always alternate histories in gaming, crops that were commercially unviable and left fallow. It's this ground which the modern Shmup creator finds itself exploring. While they're clearly based on the past, they're also a step into the future and a reaction to the present. They don't feel retro. In fact, they often feel like a startling wake up call to your fattened gaming palette.

The case in point, and the main subject of this column, is ABA Games, aka Kenta Cho.

Kenta's been following his own creative urges for some years now, with a new game arriving a couple of times a year. While all share a taste for making the player God's very own trigger finger, they've varied wildly in terms of base genetic material and the additions made. However, despite the range, there's enough of a coherent style running through them all to make the word "auteur" leap to mind.

In fact, it's interesting that one of the very few genres where the word "auteur" fits entirely comfortably is the Shmup. These are games where they're recognisably one person's vision, and elements of their sensibility can be easily pointed out throughout their entire lineage. Who's Jeff Minter, other than someone who understands his obsessions and reiterates them at every single opportunity?

Kenta's latest game is a little thing called Gunroar. It's something of a departure while still recognisably bearing his fingerprints. To download, follow the link. It's free. Get going.

Its base materials are those of the classic vertical scrolling shooter 1942. Waves of gunboats and battleship descend down the screen towards you, while islands are covered in anti-aircraft turrets to pummel you to pieces. You dodge the sheets of fire while returning your own. You know this. It's a classic mid-eighties videogame structure.

Its two primary additions are a control mechanic and a scoring mechanic. The first is to add a lockable-direction control system, allowing you to fire in a separate direction to the one you're moving in. It's identical to the system I first experienced in Llamatron, but perhaps a better comparison would be the Jeep's control system in Amiga-classic SWIV. The second addition is a scoring multiplier. This particular aspect has proliferated in modern Shmups, moving them from simple "kill everyone as quickly as you can" games to "kill everyone in a specifically clever way to score as many points as possible" ones. Gunroar's scoring multiplier is primarily related to your speed of progress. Since it's based on a push-scrolling engine, this speed is entirely up to you. You can roar on headfirst, getting into increasingly deadly situations to up your bonus; or hang back and let it fall. With these two additions, a relatively unique experience formulates.

However, despite being recognisably based around 1942, it's still presented via Kenta's traditional colour schemes and visual motifs. Everything is in soft pastels, painful fluorescents and constructed out of crystals. This creates a fascinating aesthetic response in the gamer. While you're able to discern what something is meant to be, despite how it's rendered, it really bears very little actual resemblance to its real world counterpart. Despite this, your brain makes the act of closure. However, it's less like you're fighting a battleship; more the idea of a battleship.

It's the narrative element. Not in terms of story, but rather that's clearly about something rather than a more abstract "things shooting". Perhaps "representative" would be a better word than "narrative". However, the formula of an old core with new experimental additions is something you see in all of Kenta's games, as well as most of his peers'. There's a formalist rigour to their work, in that the basic rules of a Shmup are so transparent that you can start changing single aspects with deliberate intent to see what results. In the case of Gunroar, the multidirectional fire means that rushing headlong through levels is a useable tactic in a way that it isn't with traditional forward-only guns. Or, at least, isn't in a way that's fun.

To look at some of his other works, the game before last, the left-right scrolling TUMIKI Fighters, upped the pastels and nabbed Katamari Damacy's "collect up pieces" aspects. Shoot a baddie, fly and pick up the individual pieces and they'll stick all over the ship. Any piece acts as a shield and can be knocked off. If it has a gun, it shoots too. Flying an enormously unwieldy ship is immediately enchanting.

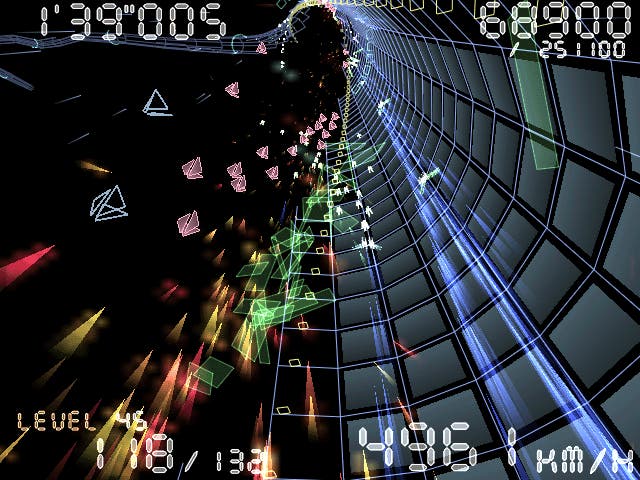

Alternatively consider his game before Gunroar, Torus Trooper, which takes a Tempest-styled into-the-screen rush, mixes it with something like Wipeout so it's essentially a race game, and then accelerates it to a sizeable fraction of the speed of light. At high difficulties especially, Torus Trooper falls down on the "game" count by having a few too many entirely random deaths. However, despite this, it succeeds in terms of pure experience. I've never been as fast in a game as I have in Torus Trooper, and even felt a little motion sickness first time I played it. Nothing's played tricks with my guts like that since I first experienced seminal high-speed racer Vroom on the Amiga. No, it's not a game you'll form an adult relationship with, but not all games exist to be that long-term partner. Some are flirty creatures meant for one-night stands. And some, like Torus Trooper, don't even last that long, and serve us best for hurried and torrid couplings in nightclub toilets. You won't marry it, but your life will be much poorer if you've never tried it.

While Torus Trooper is an extreme example, none of Kenta's games are perfect. He strikes me as someone who only knows himself through his work, as someone who implicitly understands the old "Novels are never finished, only abandoned" maxim. He'll work on a game until it's close enough to his vision, and then release it, following his muse onto the next idea. This means that all his games have an essential freshness that's easily lost when a game spends too long in development.

Which isn't to say that they're shoddy. The procedurally generated big-boss game rRootage is like what happens when a perfect snowflake goes off to war, and as exquisitely formed as a haiku. Though it certainly can be argued that it's not quite as brilliant as Hikoza T. Ohkubo's Warning Forever.

If you haven't returned to the simple shooter since the days when they ruled the earth like power-up-obsessed dinosaurs, expect to be surprised. The intensity that a modern example of the genre can express can be entirely overwhelming as the screen fills with grand geometric patterns of destruction. You'll panic, and die. You don't need to. Kenta tends to keep the convention, which many have taken, of reducing collision detection to only the very centre of your vessel, so increasing survivability. A cheat, you may think, except it's just generations of developers distilling what they love about the genre. Screens full of bullets look beautiful? Can't have them with real detection? Well... get rid of that sort of detection.

And this sort of focusing works. While it is one of the simplest sorts of games imaginable, your response is so primal that the shooter is also the one that lends itself best to writing about in pure purple prose. Hell, I've even written (bad) beat poetry about Defender. As you dance between hell's own raindrops, a clarity consumes you, much like the elation of doing that people like surfers or snowboarders laud. There's an irony that this feeling of oneness with the universe makes Shmups, despite a deathcount which rivals the average pandemic, the most spiritually affecting games in existence.

If you haven't played a Shmup in years, do yourself a favour, and remind yourself of this simple fact.

An afternoon Zen-apocalypse will do you good.