Editorial: Killing Time

What if next gen games turned to DVDs for inspiration?

Gaming is a complex business. It's also a business with a complex. Everything has to be big, long lasting and expensive. It's a philosophy observed from top to bottom. Publishers want a certain number of missions and hours, developers talk in terms of breadth of experience and replay value, reviewers complain bitterly about games that can be completed in less than an evening, and you, the people handing over hard-earned cash to play the end product, want something that will last you until you find yourself in a strong enough position to plunge another £30-40 into your hobby.

Having spent the past week scrambling around Los Angeles admiring ridiculously elaborate, grandstanding demonstrations of next generation consoles, however, I'm starting to think differently. Developers I spoke to said of the much-discussed Killzone PlayStation 3 demo that it was technically possible, but that filling a whole game with that degree of detail would be next to impossible without throwing hundreds more developers at the project and boosting the capital behind it exponentially. And, they added, that was why they felt it was less than representative. Far more likely, they suggested, were games that looked some way beyond what we were used to, taking the same shortcuts behind the scenes and developing new ways to cut corners without anybody noticing.

In other words, Killzone might have to cut down on some of the technical delights afforded to them by the hardware in order to live up to some prescribed game length.

But what if Killzone wasn't a traditional "whole game"?

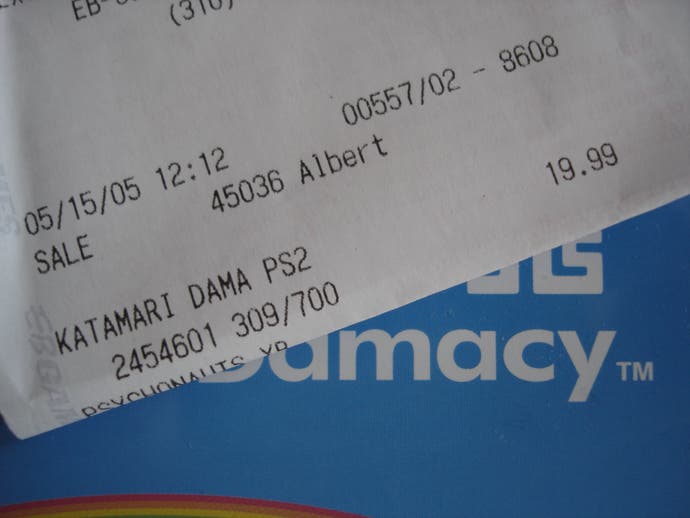

On my day off, I went shopping. I bought some new jeans and "daps" (did I get that right?), and stumbled into EB. On a whim, I spent $19.99 on the American version of PS2 cult classic Katamari Damacy, because it was cheap. Even though I'd already played the Japanese version enough to get my fill, it had been a good few months, and I was prepared to spend that much to play through it again - the English translation being a bit of a bonus.

Later that week, shopping and console launches behind me, it dawned on me: I'd just impulse-bought something I'd already played through in a few short hours, purely because it was within a price bracket I considered reasonable.

It's the DVD or VHS model, isn't it? You see something at the cinema or round a friend's house and it bowls you over. A few months later, you buy it for yourself because you want to add it to the collection of things you can revisit when the urge hits you, or when the right people are sitting on your couch, and you can soak it up again in a single sitting - even though the initial return is just a couple of hours or so of entertainment.

If you bought a game for £15, would you accept just two or three hours of entertainment? Probably not.

Simply dropping games of the current prescribed size to £15 wouldn't guarantee anything either. Poor performers often hit £15 quite quickly, Minority Report being one example (and that was under a tenner in less than a month it was so bad), but people aren't automatically going to pick something up simply because it's cheap. Some will, which, to stick with Minority Report, is reflected to a certain extent the charts, but then that's more of an awareness issue to do with the impact of the stubbornly entrenched games media (and another editorial altogether). If anything, the lower price will heighten the suspicions of the core gamer audience.

But what if you bought a game for £15 and it looked like Killzone 2, or MotorStorm, and lasted two or three hours from start to finish?

After playing through it in an evening, you could return to it a couple of weeks later with a friend and tackle it co-operatively. You'd try it again yourself a few months later and discover different solutions to the same problems. You'd realise that the multiplayer mode, though seemingly limited, had its own open-ended charm that, given the quality of the visuals and the solidity of the mechanics, kept you glued to the screen - far more so than DVD "extras" ever manage to do.

Arguments about rentals soon towering over actual sales are bound to pop up here, but if the DVD industry can sustain it, why not games? Maybe rentals would have to be shelved for a while to ease the transition, he says, prompting gasps and sneers, but clinging on to existing retail and rental models when the risks are so high is surely a worse idea than temporarily restricting something like that anyway?

Another issue is that DVDs are extra profit for a film on top of the box office return. But while that's true, the development costs are on a completely different scale. DVD sales alone (in a lot of cases) couldn't offset the cost of blockbuster film production, but DVD-priced game sales could conceivably offset the cost of blockbuster game development.

[Editor's note: This is usually where the arguments kick off, with the publisher camp insisting the economies of scale wouldn't make up for the lack of revenue, while those calling for cheaper prices claim the opposite. Personally, I reckon until someone actually starts releasing gaming blockbusters at impulse prices, we'll never know one way or the other and we'll just keep on arguing....]

And you can bet your bottom dollar, to use an expression I'm disappointed not to have heard even once in the three years I've been going to E3, that people who don't already play games would take an interest if the bar for entry was that much lower - and with so much multimedia functionality going into the Trojan media gateways that are PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360, there's a lot to suggest that non-gamers could be tempted, having watched in awe as their best mate played through Killzone 2 in glorious high-definition on a box that contributes far more to the lounge than it used to, and without the hefty footprint and mess of cables.

Having shorter games that cost less is hardly a revolutionary idea, of course. id Software built an empire on the shareware concept, as have others, and indeed our own Kristan Reed wrote a piece recently expressing similar views. But while many have asked for shorter games more often, I'm suggesting shorter, better-looking games instead. Development would still take similar lengths of time. Does that make sense? Given that so many critics wonder out loud where people are going to find all the time and money to buy the next year's worth of top titles, development costs are spiralling to keep raising the technical bar, and the designers themselves are openly entertaining the notion of throttling back just to make sure they can get things done over a prescribed in-game distance, perhaps it does. Either way, surely it's an idea worth reconsidering as next-generation graphics start to emerge?

After all, we already have some shining examples of classic, fantastic-looking games that you can complete in one or two sittings. Given a lower price point, you'd feel much more comfortable buying them, finishing them quickly and returning to play back through them a few months later, and crucially so would the average console owner. One of my favourite games of all time, Resident Evil 2, leaps straight to mind, but there's another game we champion around here all too often that would easily fit the bracket, and it makes us wonder just how well it would have done under these sorts of conditions. That game is ICO.

We're often told that gaming could be the new movie business, and that gaming revenues are closing in on those generated in Hollywood. Whether you're convinced of that or not (and I'm not), it seems that we could learn a great deal more from them if we thought harder about it. Given a model of extraordinarily good-looking, movie-length, DVD-priced blockbusters, is it conceivable that gaming could take over Los Angeles, instead of just giving me somewhere to eat burgers, buy jeans and pick up some imports for a week each May?

Just my $19.99. Now, where did I put my lonely rolling stars?