A team of Dota 2-playing AI bots beat the pros - and now they're gunning for more

I need your clothes, your boots and your courier.

On 5th August, five expert Dota 2 players sat down to play against a team of bots created by non-profit research lab OpenAI. They lost decisively. Just a few days from now that same team of bots, perhaps with the benefit of a few more weeks of training, will appear on stage at the biggest tournament in Dota 2 - The International - and play against a team of the world's best professional players. Winning there that would be a huge victory, a milestone for both AI and the games industry, and after seeing the bots' performance earlier this month it seems like the most likely outcome. You might be forgiven for feeling like this was the end of an era for game AI as we know it.

It all feels a bit sudden, too. At last year's International tournament OpenAI were a surprise appearance, turning up to show off their bot that could play 1v1 Mid - a simpler custom game mode for two players - and beat top professionals. It was an impressive display, but it also felt like the kind of game an AI would be naturally good at. It was simple, short, with very clear goals and a lot of emphasis on reaction time. The real challenge, everyone pointed out, would be playing the full game.

OpenAI's bots don't play the full game quite yet, but less than 12 months later they are surprisingly close, far closer than myself or many of my peers would have guessed they'd be this time last year. With a few notable game mechanics disabled, and only 18 of the 115 heroes available to play, the bots nevertheless exhibit precise calculation, aggressive fighting styles and an unstoppable sense of momentum. When they're not exhibiting superhuman skill, they're throwing out decade-old Dota 2 conventions and finding new ways to play heroes, distribute resources and take objectives.

One reason they play so differently to humans is that, obviously, they aren't human: the bots can make calculations far beyond even the top professionals, which leads to superhuman degrees of efficiency and precision. But a more important reason for their unusual style of play is the way they were built. OpenAI's bots aren't coded using expert insights and thousands of rules, nor are they shown examples of how humans play to learn from. Instead, OpenAI's engineers used something called Reinforcement Learning to allow their bots to start with no knowledge about Dota 2 - no knowledge about video games at all - and teach themselves to be better than the best.

The way this works, like all artificial intelligence, is both more and less complicated than it sounds. Every fraction of a second, OpenAI's bots receive more than 20,000 observations from the Dota 2 API. These are numbers that describe everything from how much health the bot has, to the number of seconds until a debuff wears off on a particular enemy. At the same time, there are thousands of actions they can choose to take - moving, attacking, using spells or items, all on various targets or locations on the map. The challenge for the bots is figuring out which of the 20,000 observations are important at this precise moment, and which actions are more likely to help them win, if any.

The clever bit happens in between: a neural network, which gathers together all of these inputs and outputs, and connects them together. One of the most important roles this network has is applying weights to each input - multipliers that can increase or decrease the impact of a particular input on a particular output. Think of it like an audio mixing desk, and the weights are various sliders and knobs that make some parts of a song louder or softer in the final composition - except in this case, there are 20,000 instruments all playing at once, and you need to find a mix that works for the whole song, start to finish, even if the performers start improvising.

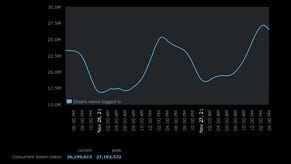

OpenAI's bots start with these weights chosen randomly, which makes them play completely chaotically - someone who has never played a video game before could still beat them at this stage. But over time, the bots receive feedback - rewards when they gain gold or kill a hero, penalties when they die - and each time they tweak the weights on their own neural network a little. Soon, some of the random bots are playing just a little better than others, and the weaker ones are replaced with copies of the stronger ones. Given enough time - OpenAI's system plays over 900 years of Dota 2 a day, across hundreds of servers - bad bots become average, and then good, and then great, and then, hopefully, superhuman.

Superhuman is a funny word. In their exhibition match earlier this month, there was no question that OpenAI's bots were better than their human opponents in games one and two. But in the third game, a bonus round where the audience picked heroes for the bots, they performed far worse, stumbling at first and then falling apart entirely by the end. This wasn't just a case of audience sabotage - the bots played worse than a human team would have given the same setup, because they were determined to play the same aggressive playstyle, even when the situation didn't warrant it. This all comes back to how the bots learn, and how they relate a good thing happening to an action they took in the past. Aggressive styles of play make it easy to connect cause and effect: this hero died because I fired a huge laser at him with my finger. Planning for the long game requires looking far into the future, and being able to connect events 10, 20 or 30 minutes apart. Gathering gold for 30 minutes to become powerful enough to win the game is a lot harder to study and learn from than a giant finger laser.

So if OpenAI's bots do win this week, and it's looking likely they will, what does this actually tell us? They're good enough to win, but not so good that Dota 2 has been entirely cracked open. For AI researchers, a win is a win - victory on the big stage will be another landmark in the history of AI. For the games industry, it might not be quite as meaningful. For one thing, OpenAI's approach just isn't practical for all but the richest games studios working today. It required months of training, millions of dollars worth of equipment and computation time on remote servers, and some incredibly smart engineers who worked on nothing else. But the bigger question is what bots like this would actually be useful for, if anything.

For OpenAI, beating humans at Dota 2 is part of a longer journey towards making AI work in the real world. For game developers, perfect AI are most useful if they model how humans play games in some way. Suppose you want to test how balanced a multiplayer game is, so you train some bots to play it. Superhuman bots that teach themselves to play the game will only reliably tell you if the game is balanced for bots. It doesn't tell you how people will learn, what existing skills and knowledge they might bring, how they might interpret rules or what strategies they might develop. With a bit of tuning, they might serve as a reasonable replacement for Dota 2's own in-game bots, but practicing against them won't prepare you for the breadth of strategies and playstyles humans exhibit in real matches.

So why should we be excited? What's in it for us, as players, if OpenAI get better at Dota 2 or if Google suddenly develops the world's best Starcraft 2 bot? For one thing, it's a reminder that these games we play every day still contain unknown multitudes. OpenAI's bots might have superhuman reflexes, but they also break traditions - they send their support heroes to get solo safelane farm; they send four heroes to pressure towers in the first minute. Superhuman bot performances will always challenge us to keep searching for new secrets and new strategies, and provide us with a goal we can constantly strive towards. But a better reason to be excited is that, like all steps forward in technology, it will help make possible things we can't even conceive of yet. New genres of games where we train bots to complete challenges; stand-in bots that mimic our level of ability to replace us if our internet dies; a SpaceChem-like design challenge where we devise games AI can't learn to win. The true potential of rapidly-learning game-playing AI won't be something ordinary or foreseeable, it'll be something unpredictable and wild. OpenAI's victory (or defeat) this month doesn't represent an end for any part of game AI, nor an end to humans competing to be the best they can be at playing games. It's a new beginning for something entirely different.